If You Don't Build It …

A slide-show essay on Seattle's floating dome, Edmonton's Omniplex, and other great unbuilt stadiums.

-

CREDIT: Image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates.

CREDIT: Image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates.Failure, like success, is grander in New York City. Indeed, no modern stadium project failed as spectacularly as Manhattan's West Side Stadium. Proposed by the mayor's office in 2004, West Side Stadium was billed as the ultimate sports and entertainment complex: a host venue for the 2012 Olympics, a home for the New York Jets, and a 200,000-square-foot convention center. The project was dead by 2005.

West Side Stadium had a lot going for it: Mayor Michael Bloomberg was behind the project, building unions supported it, and business interests love urban development. But taxpayers didn't want to finance a stadium, neighborhood activists didn't want Hell's Kitchen to become Times Square, and Cablevision—fearing a shiny, new competitor to Madison Square Garden—allied itself with anti-stadium activists to run a propaganda campaign on television and radio. -

Image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates.

Image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates.There are three factors that nearly always contribute to stadiums going unbuilt: a contentious location, an overly ambitious design, and the presence of other viable stadium options. An 85,000-seat, $1.4 billion stadium on public land on the Manhattan waterfront was probably doomed from the get-go. West Side Stadium's official end came when New York state legislators refused to allocate public funds. The 2012 Olympics were awarded to London. In 2010, the Jets took up residence in New Jersey's New Meadowlands Stadium, which was privately funded, has friendly neighbors, and offers plenty of parking.

-

Photograph by Wil Blanche. © 1955 all rights reserved.

Photograph by Wil Blanche. © 1955 all rights reserved.West Side Stadium was not the first pie-in-the-sky sports construction project to fail in New York. In the 1950s, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley sought a replacement for Ebbets Field, which had a seating capacity of only 32,000. He recruited R. Buckminster Fuller to help design a multi-use stadium with a translucent dome, telling the eccentric architect he was "not interested in just building another baseball park."

According to historian Glenn Stout, the absurdity of the dome design—its feasibility will forever remain untested— doomed negotiations between O'Malley and city construction commissioner Robert Moses. O'Malley had been hoping to secure land for a privately built stadium at a Brooklyn site across the street from what's now known as Atlantic Yards (currently home of a modern, divisive stadium project).* Moses had concerns about traffic at O'Malley's proposed site; he tried to persuade O'Malley to move the Dodgers to Flushing Meadows, where the city would build a stadium and rent it to the franchise.

The Dodgers instead moved west to a land without rainouts, where O'Malley (eventually) rid himself of domed dreams. Moses got his city-owned Shea Stadium at Flushing Meadows with the arrival of the expansion Mets in 1962.

*Correction, March 7, 2011: This piece originally stated that the Brooklyn Dodgers once proposed building a domed stadium on the "site now known as Atlantic Yards." The Dodgers' stadium was to be located across the street from Atlantic Yards. -

Drawing of CREDIT: proposed Seattle floating stadium. Document 7216, Published Document Collection, Seattle Municipal Archives. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons 2.0 generic license.

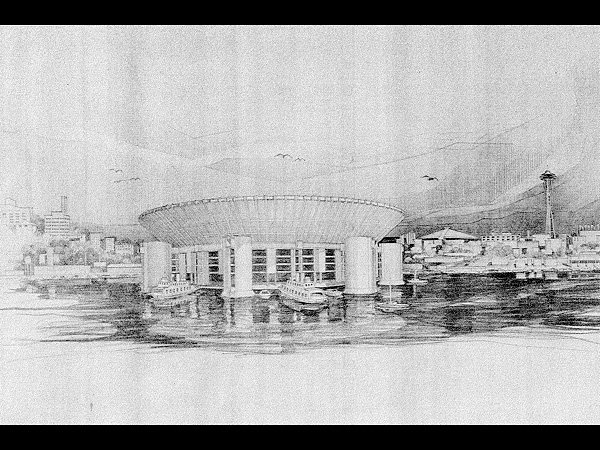

Drawing of CREDIT: proposed Seattle floating stadium. Document 7216, Published Document Collection, Seattle Municipal Archives. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons 2.0 generic license.R. Buckminster Fuller would have been at home in early 1960s Seattle. The city, which built the Space Needle and monorail as part of the 1962 World's Fair, was preoccupied with futuristic architecture and infrastructure. In 1963, a collective of an architect, engineer, and construction firm proposed a stadium that would float in the Puget Sound just blocks from the fair site.

The floating dome would have featured a retractable roof, monorail access, and even a ferry dock. The design, popular among Seattleites, was written up in Sports Illustrated and backed unanimously by King County commissioners ahead of a 1966 funding referendum. Questions about the project's feasibility and reticence to fund a stadium in a city with no professional franchises led to the referendum's defeat.

Seattle finally got a pro sports team in 1969, when the short-lived Seattle Pilots came to town. Major League Baseball allowed the move on the condition that voters pass a $40 million bond measure for a new domed stadium. The measure, presented as part of a larger $815.2 million capital improvement plan, passed with more than 60 percent of the vote. The floating stadium—with its wacky design and surreal location—was sunk, and the Kingdome was born. -

Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives.

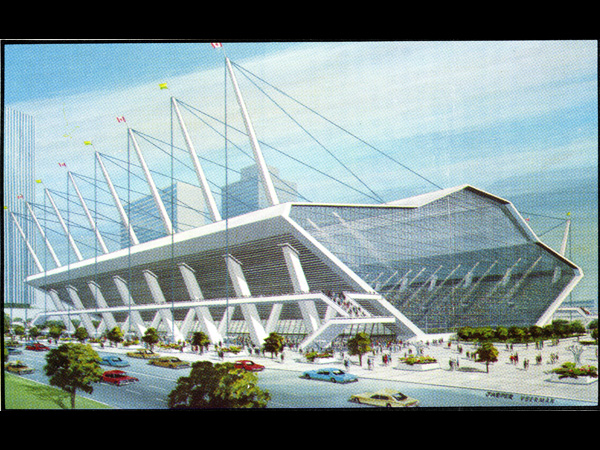

Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives.If Seattle's floating stadium was a fleeting fantasy, downtown Edmonton's Omniplex was a lingering impossibility. The multipurpose stadium and convention center was a matter of public debate for eight years before succumbing to the common maladies of overwrought design, a challenging location, and more-manageable (and affordable) alternatives.

Building a stadium in any downtown is a political challenge. Using taxpayer funds to build a facility that features a football field suspended in midair over an ice rink is an even bigger challenge. A 1968 city pamphlet claimed the Omniplex would be "as bizarre in concept as the Expo pavilions (in Montreal) … as well as much more weatherproof than the Astrodome."

In spite of that stirring sales pitch, the Omniplex went down the tubes. Between 1968 and 1971, cost estimates increased by more than 50 percent because of design changes and ballooning downtown land values. Instead of a stadium that cost more than its parts were worth, Edmonton officials modestly constructed a separate hockey arena and convention center in the 1970s. -

Image courtesy of the Detroit Tigers and Gary Gillette, Society for American Baseball Research.

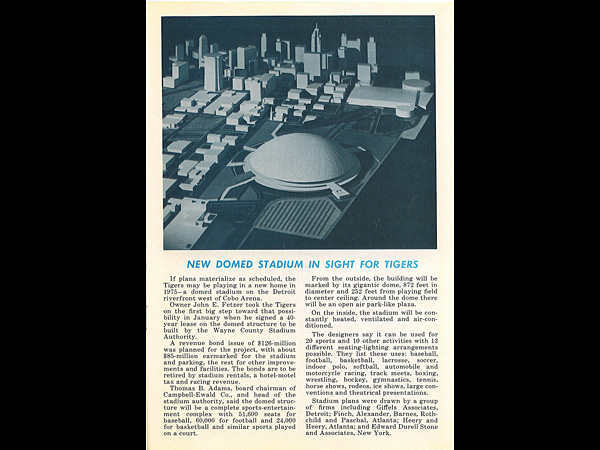

Image courtesy of the Detroit Tigers and Gary Gillette, Society for American Baseball Research.In January 1972, Detroit Tigers owner John Fetzer signed a 40-year lease on a proposed domed stadium. While the waterfront facility would have lacked the Omniplex's strange aesthetic charms—"From the outside, the building will be marked by its gigantic dome," claimed an article in the 1972 Tigers Yearbook—it would have brought the multipurpose craze to its apex, hosting all four of Detroit's professional sports teams, along with "horse shows, rodeos, ice shows, and large conventions."

The multipurpose stadium offers its proprietors a unique opportunity for civic self-congratulation—a single stadium for all people!—and as many revenue streams as it has uses. But such ambitious projects are correspondingly difficult to execute, involving numerous vested parties and a more accommodating architecture. In Detroit, corners were cut, and a judge ruled that lawmakers had misled the public on the stadium's financing. With the Tigers already playing in a perfectly suitable stadium (it would last through 1999) and plans already under way for the 80,000-seat Silverdome in suburban Pontiac, this dome was dead. -

Armour Field, Chicago, Ill. Drawing by Rael Slutsky, courtesy of Philip Bess and Thursday Associates.

Armour Field, Chicago, Ill. Drawing by Rael Slutsky, courtesy of Philip Bess and Thursday Associates.Most stadiums have to overcome the pitfalls presented by design, location, and competition. Armour Field was a conscientious effort to confront them. In 1987, the White Sox were ready to replace their ancient home, Comiskey Park. As a protest to the unimaginative plans floated by the ballclub, Chicago architect Philip Bess took it upon himself to conceive an alternative. Armour Field, a scaled-down stadium in the fashion of Wrigley Field and Fenway Park, was designed "to illustrate that a compact-footprint neighborhood ballpark could provide fan comforts and generate industry standard revenues."

In his book Playing the Field, Charles C. Euchner speculates that Armour Field—which received favorable notices in newspapers and trade journals—helped inspire the wave of retro-urban stadiums that began in the 1990s with Baltimore's Camden Yards. The White Sox, who could not be convinced to adopt a bold, unusual design, ended up playing in the conventional-looking Comiskey Park. -

Fenway Park in Boston.CREDIT: Photograph by Elsa/Getty Images. © 2010 Getty Images.

Fenway Park in Boston.CREDIT: Photograph by Elsa/Getty Images. © 2010 Getty Images.An alternative to building a nostalgic ballpark is to simply reproduce an existing classic. The Red Sox flirted with this idea in the late 1990s, proposing a new, larger Fenway Park (complete with a new Green Monster). Club officials claimed the facsimile was necessary for the franchise's continued economic viability.

The $665 million plan—backed by the mayor, governor, and state legislature—was slowed in 2000 by the Boston city council. The council's skepticism was rooted in familiar places: expectations of cost escalations and questions about the necessity of a new stadium. Unlike Seattle, where public funding was a prerequisite for the acquisition of a team, lawmakers and citizens could safely weigh the consequences of public funding. The Red Sox, after all, were never going to leave Boston.

Economic sanity won the day. In 2005, a new ownership group under the leadership of John Henry committed to renovating the old Fenway—a vindication of the Bess model of humble neighborhood ballparks and a victory for Sox fans who organized on behalf of their beloved stadium. The renovations, which began with the addition of Green Monster seats for the 2003 season, have increased Fenway's seating capacity by almost 10 percent. The makeover has continued in 2011, with new HD video screens and refurbished wooden grandstands among other improvements. -

Drawing of proposed Rays Stadium. © CREDIT: St. Petersburg Times/Zuma Press.

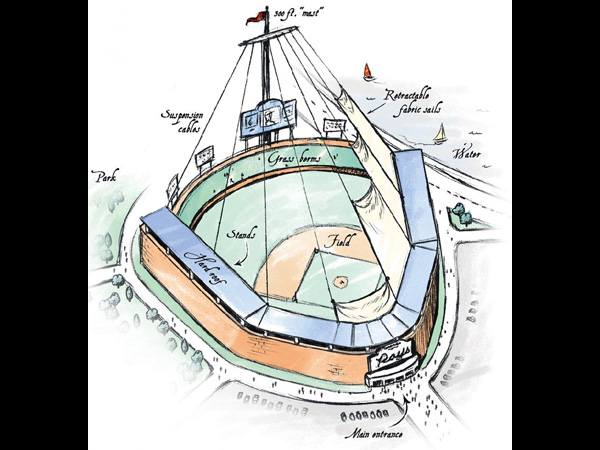

Drawing of proposed Rays Stadium. © CREDIT: St. Petersburg Times/Zuma Press.If Fenway is beloved, Tropicana Field is merely tolerated. The home of the Rays is famous for nothing save perhaps the irksome catwalks strung across its ceiling. Even so, the plug was pulled on a potential replacement just seven months after it was proposed in 2008.

The Rays were unable to build momentum for the project even with the franchise in the midst of its first-ever winning season. Club officials admitted that something about the proposed Rays Ballpark failed to resonate with the public—perhaps its artsy design (a pulley-operated canvas roof reminiscent of a sailboat) or its St. Petersburg waterfront location.

The Rays' futile quest is a perfect demonstration of the value of leverage. With none of it—the team's lease on Tropicana Field lasts through 2027—the club is hamstrung. Perfectly aware of this, Pinellas County commissioners recently voted down a tax extension that would have gone toward financing for a new park. -

Photo courtesy of CREDIT: Los Angeles Football Stadium.

Photo courtesy of CREDIT: Los Angeles Football Stadium.If the Rays were a football team, they would have heard from Ed Roski by now. The Los Angeles developer, hungry for a team in need of relocation, has unveiled a fully realized, "shovel-ready" venue proposal, complete with Blade Runner-esque renderings and a movie-style trailer.

Roski, who is also the principle financier behind a newly proposed multipurpose absurdity at UNLV that makes the Omniplex look feasible, appears to be doing everything right in this instance. He has secured the land itself and the necessary building permits; his stadium is privately financed; and until very recently, it was the only credible proposal around for an L.A. stadium. Alas, Anschutz Entertainment Group (owner of the Staples Center) has entered the conversation, announcing ambitions to build a football stadium next door to its downtown basketball and hockey arena.

While AEG's involvement has kicked off a new round of team carousel speculation, the corporation's plan seems dubious. AEG wants a retractable-roof stadium built on publicly owned land in a crowded downtown. In the breadth of its aspiration—and in the wealth of its potential opposition, namely Ed Roski—AEG's proposal is reminiscent of Manhattan's West Side Stadium. A warning to Los Angeles football fans: Don't get too excited about your new downtown sports cathedral. If history tells us anything, it will be America's next great unbuilt stadium.

In 1970, construction began on Seattle's Kingdome. Thirty years later, the 55,000 seat stadium was destroyed. Its implosion, the largest demolition of its kind in recorded history, was a national event, broadcast live on ESPN Classic. You can still buy Kingdome implosion memorabilia in Seattle gift shops.

With the Kingdome now reduced to rubble, it's easy to forget that the enormous stadium almost never existed. In the early 1960s, when Seattle first considered building a multi-sport stadium, there was a far more alluring plan on the table. Designers proposed a floating, retractable-roof stadium that would have sat in Elliott Bay just west of Seattle Center—home of the Space Needle and the 1962 World's Fair.

There is little doubt that such a stadium, if constructed, would've become the icon that the characterless Kingdome never was. While the stadiums we erect can embody both civic pride and civic catastrophe, unbuilt stadiums reflect our ambitions and our shortcomings more brightly. The ballparks we imagine, design, and fail to see through to completion are testaments to our egos, our metropolitan insecurities, our ever-changing sense of aesthetics, and our growing economic expectations.

Launch a slide-show essay on North America's unbuilt stadiums.