The Washington Post published a dispatch from Youngstown, Ohio on Wednesday that chronicled the frustrations of local Democratic leaders who think the national party is ignoring the concerns of “working-class” voters. “It doesn’t matter how much we scream and holler about jobs and the economy at the local level. Our national leaders still don’t get it,” the county’s Democratic Party chair told reporter William Wan. “While Trump is talking about trade and jobs, they’re still obsessing about which bathrooms people should be allowed to go into.”

Here’s how Wan summarized similar arguments: “Since the election, Democrats have been swallowed up in an unending cycle of outrage and issues that have little to do with the nation’s working class … such as women’s marches, fighting Trump’s refugee ban and advocating for transgender bathroom rights.”

While it may be true that Democrats are failing to properly communicate how they’d revitalize the economy if elected, the separation of issues that affect the “working class” from those that affect women, targets of racial and religious discrimination, and transgender people is an error that gravely misrepresents the reality of people’s lives. But to recognize that women, people of color, religious minorities, and transgender people are also affected (disproportionately, at that) by the struggles of the working class would raise a truth that’s equally uncomfortable for middle-American political operatives and mainstream political journalists: When they say “working class,” they don’t mean all working-class people. They mean white, straight, cisgender, U.S.-born men, just as people who say the Democrats have a “religion” problem mean a white religion problem.

It is astonishingly narrow-minded to claim that “women’s marches, fighting Trump’s refugee ban and advocating for transgender bathroom rights” have “little to do with the nation’s working class.” There are transgender American women doing low-paid wage work in places where they’re scared to or legally prohibited from using the restroom. When they get UTIs from holding their urine until they can get home and their health insurance (if they have any) won’t cover antibiotics, is that a working-class issue or a transgender issue? When a working-class immigrant woman is abused by her husband and can’t afford to leave, but also can’t report him to the police for fear of deportation, is that a working-class issue or an immigrant-rights issue? When the mosque of a working-class Muslim man is burned down and he can’t afford a car to travel to another place of worship two counties away, do we chalk his troubles up to stagnating wages, Islamophobia, or both? When a black man gets passed over in favor of a less-qualified white one for one of the few factory jobs left in town, or gets fired because he’s gay (which is still legal in a majority of states), is he suffering from racism, homophobia, or globalization? Do working-class women with no access to affordable child care, contraception, or abortion coverage have woman problems or no-good-jobs problems?

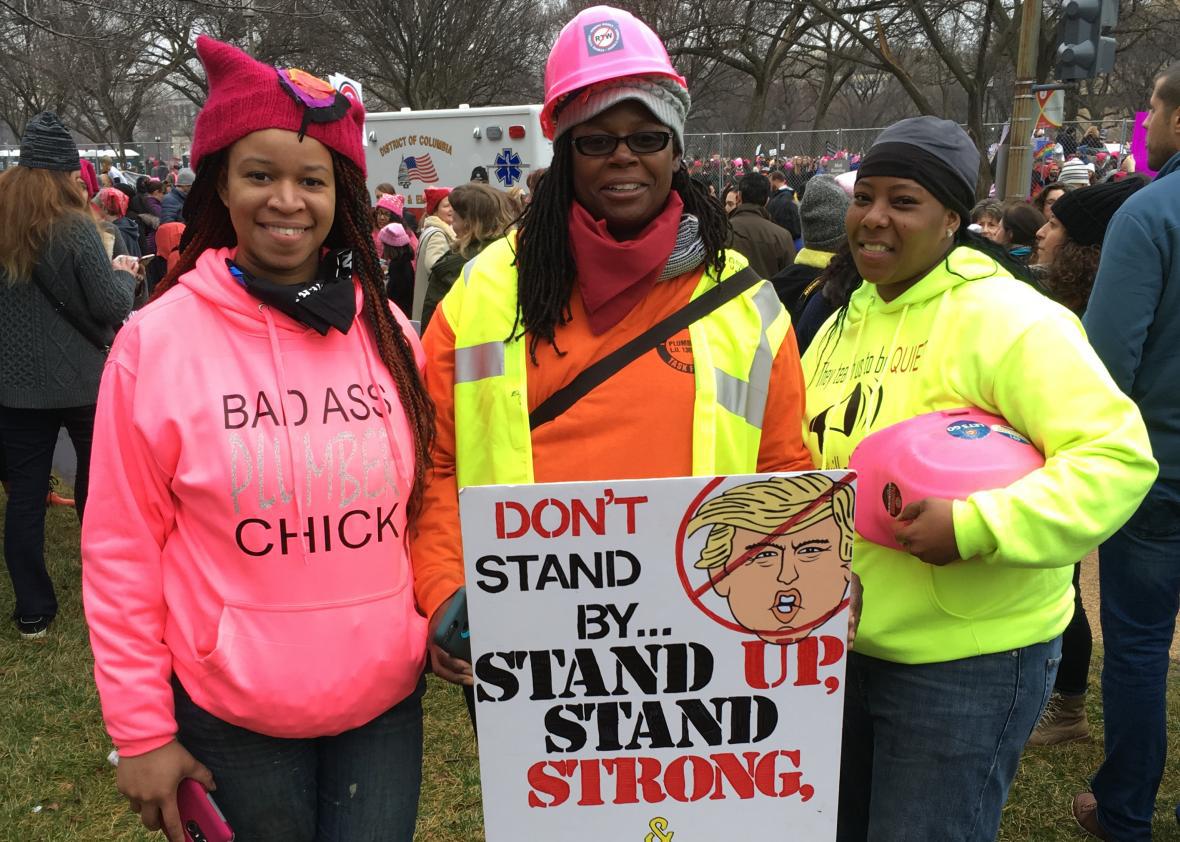

Listing the hundreds of women’s marches that took place across the country in January—and mobilized millions of people in megacities and small towns alike—as an “issue” is weird enough. But also: No one who attended or read about the women’s marches can credibly claim that the events were divorced from the concerns of working-class people. In Washington, D.C., where I reported from the main march, dozens of unions from around the region brought working women to protest for fair wages, equal pay, and an end to workplace sexual harassment. The unapologetically progressive platform march organizers espoused put a sharp focus on worker’s issues, demanding nondiscrimination employment protections and expressing support for a living wage, strong unions, and “healthy work environments.” If Democrats can’t get Youngstown’s voters to care about a movement that explicitly supports their interests, that’s an indicator of a lackluster communication strategy and the sexism of Youngstown’s voters, not evidence that the movement is irrelevant to the needs of this slice of the population and too trivial for Democrats to gush over.

In his article, Wan does make one nod to the idea that working-class people can also be people who aren’t white cisgender men who only care about their needs but also often vote against their own best interests. He quotes Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress, who says the decision between an economic focus and a civil-rights focus is a “false choice.” This is true. It is not, as Wan paraphrases, “[taking] offense at the idea of ceding focus on causes such as gay rights, anti-Muslim discrimination, racial disparity, abortion, and women’s rights for the sake of votes.” Tanden’s point is not that the Democratic Party should soothe white men’s fears by ceasing talk of anything that doesn’t obviously apply to their exact lives. It’s that the party need not sacrifice votes to fully advocate for issues that do, contrary to the narrative presented in Wan’s piece, matter deeply to people in Youngstown and everywhere. Working-class issues are inextricably intertwined with civil rights, gender inequities, discrimination against religious minorities, and LGBTQ protections. The answer to Youngstown’s frustration is better education and communication about these connections, not ignoring the struggles of dozens of demographic groups for the sake of one who feels left out.

The fact remains that black and Latina Americans are poorer, by median income, than white ones, and projections say the American working class will be majority people of color by 2032, 11 years before the general population. Racism, religious persecution, and immigration are, and always have been, working-class problems, too. The problem with communicating this, and that perhaps Youngstown Democrats don’t want to admit, is that white working-class people may be more motivated by racism, which Trump inflamed and rewarded, than by classic working-class interests. Polls upon studies upon analyses have shown that Trump voters are overwhelmingly animated by birtherism and anti-black racism, have a higher-than-average income, and are no more likely to be unemployed or victimized by the tides of immigration and globalization than other Americans. In other words, plenty of poor and working-class people voted against Trump—they just weren’t as white as the ones who voted for him. So when you hear people clamoring for Democrats to take a step back from their elite worlds of gender-neutral bathrooms, #standwithPP profile pictures, and pro-immigration airport protests to listen to working-class people, strive to hear what they’re really saying: Listen to those voters, but only if they’re white.