Michael Wear, who led faith outreach efforts for Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign, believes the Democratic Party has a religion problem, and in an interview with the Atlantic, he sketched it out.

“[T]here’s a religious illiteracy problem in the Democratic Party,” he said. “It’s tied to the demographics of the country: More 20- and 30-year-olds are taking positions of power in the Democratic Party. They grew up in parts of the country where navigating religion was not important socially and not important to their political careers.”

For Wear, the party needs to develop a comfort with religious language, open itself to anti-abortion Democrats instead of closing off anyone who disagrees on choice, and better engage with the moral questions around abortion and other issues that touch religious belief. “Reaching out to evangelicals doesn’t mean you have to become pro-life. It just means you have to not be so in love with how pro-choice you are, and so opposed to how pro-life we are,” said Wear, later adding, “It doesn’t help you win elections if you’re openly disdainful toward the driving force in many Americans’ lives.”

That last line comes after Wear bemoans reports that “high-level Democratic leadership” was uninterested in reaching out to white Catholics or white evangelicals, a point he also made recently to Slate’s Ruth Graham. He treats it as incidental—an example of how the party failed, nothing more and nothing less—but the reality is that it’s central to the question of the Democratic Party and its relationship to religious voters. When Wear says the party has a “religion problem,” what he means is that the party has a white religion problem. And that is a very different problem from the one he describes during his interview.

First, the facts. Among the most religious groups in the country are black and Latino Americans. According to Pew’s Religious Landscape survey, 53 percent of black Americans and 39 percent of Latinos say they participate in Scripture study or religious education groups at least once a month, compared with 30 percent of white Americans. Seventy-three percent of blacks and 58 percent of Latinos say they pray “at least daily,” compared with 52 percent of whites. Forty-seven percent of blacks and 39 percent of Latinos say they attend religious services at least once a week, compared with 34 percent of whites. And a whopping 75 percent of blacks and 59 percent of Latinos say religion is “very important” to their lives, compared with 49 percent of whites.

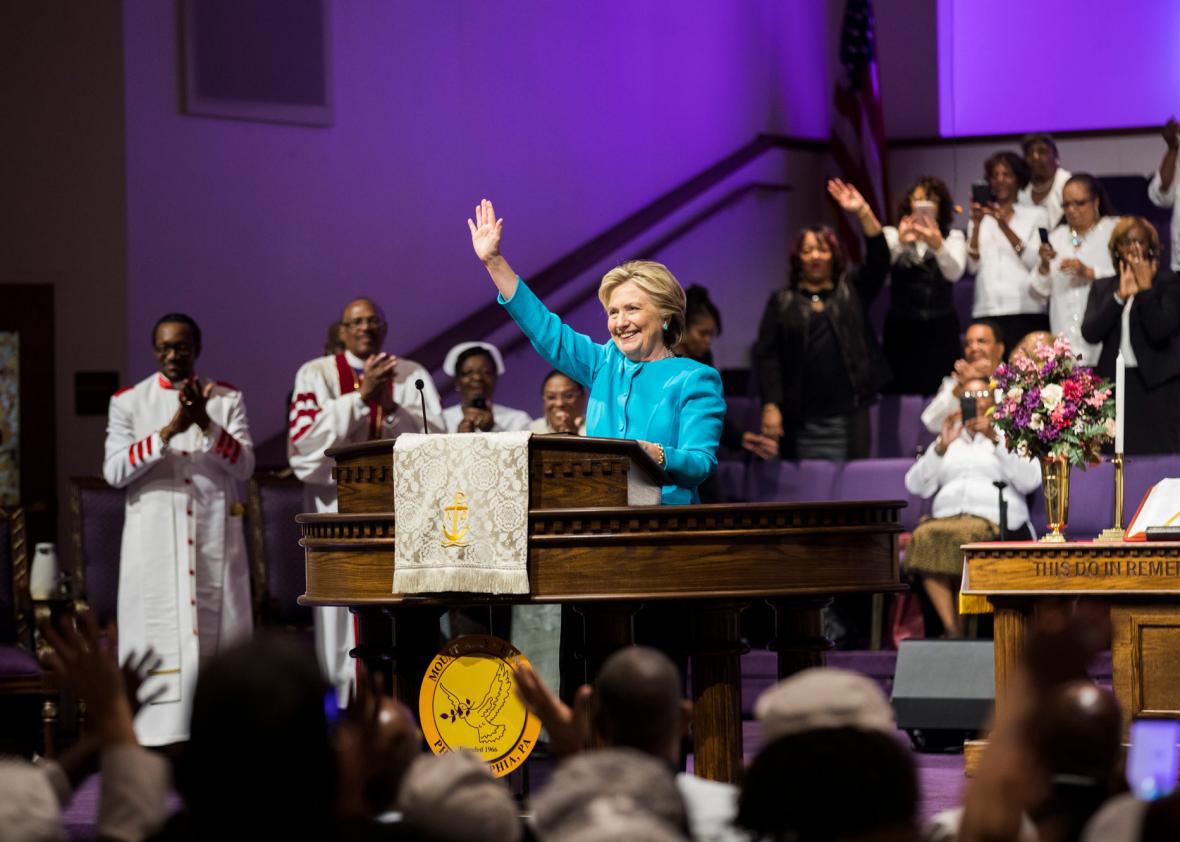

These voters back Democrats, overwhelmingly. In the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton won 67 percent of self-identified Hispanic Catholics and the vast majority of black churchgoers. She also won 71 percent of Jewish voters and 62 percent of voters who belong to other religious faiths and traditions. She suffered a crushing defeat among white evangelicals—losing them 16 percent to Trump’s 81 percent—and she lost white Catholics by an almost 2–1 margin, 37 percent to 60 percent.

Because white Christians are the majority of religious voters, and Clinton lost the majority of white Christians, you could say (as Wear does) that these numbers represent a “religion problem” for Democrats. But then to make that claim, you have to ignore race. You have to ignore that Democrats do extremely well with believers of color, Christian or otherwise. You have to ignore stark social and theological divides between black and white Christians, who historically have not understood politics and the Gospel in the same way. You have to ignore the fact that, in North Carolina, the Democratic Party won the state’s governorship on the strength of a movement rooted in black churches and tied to religious leadership. Most importantly, you have to ignore that Democrats lost the large majority of white voters, continuing a trend that dates back to 1968.

At this point, you have to answer an interpretive question. Are Democrats losing a collection of groups that happen to be white—religious voters, working-class voters, etc.—or are they losing whites specifically, with those subcategories following from that fact? Given the stark racial divides in those categories—Democrats win nonwhite religious voters by the same margins that they win nonwhite voters without college educations—the broad answer is clear: The Democratic Party doesn’t have a religion problem as much as it has a white voter problem. That white voter problem emerged in the aftermath of the civil rights movement as a resentful backlash to perceived disorder and unfairness and has gotten worse with almost every subsequent presidential election. Those Democrats who won the White House despite this problem did so by either distancing themselves from black communities and black activists (Bill Clinton and “Sister Souljah”) or presenting themselves as a break from more traditional black leaders like Jesse Jackson, unburdened by a sense of historical grievance (Barack Obama). Neither approach survived contact with the nation’s racial politics, and Obama in particular was quickly racialized by events.

It is far too simplistic (and inaccurate besides) to say that this white voter problem is purely a product of racial animus. But it does reflect the nation’s history as a herrenvolk democracy, where white Americans (or more precisely, those Americans of direct European descent deemed white) possessed primary access to opportunity, advancement, and upward mobility, as well as the full rights of citizenship. It reflects the standing assumption of white pre-eminence—the idea that the priorities of white Americans ought to drive the priorities of the nation at large. It reflects latent (and not so latent) resentment, tied tightly to race. And it reflects the deep, almost subconscious ways in which many white Americans hold (and have held) a zero-sum view of politics, where gains and benefits for nonwhites are necessarily an imposition on their status.

How the Democrats can fix this white voter problem in a way that repairs the party’s fortunes without sacrificing its liberalism or its most vulnerable constituents is a separate and difficult question. But to answer it, we have to acknowledge it. Michael Wear misses the forest for his particular tree. We should try to avoid the same mistake.