More than 500,000 demonstrators came out for Saturday’s Women’s March on Washington, a protest that began with one woman’s Facebook event less than three months ago. In the weeks since the election, the march attracted seasoned organizers and celebrity speakers, and spawned sister marches around the world. It was a grass-roots effort that took on a life of its own, exceeding all turnout projections to become what is surely one of the largest single worldwide events of all time.

Unbeholden to any single advocacy group or political party, organizers established an unapologetically progressive platform that recognized the breadth of issues that affect women’s lives. March organizers took pains to position the event in general opposition to the conditions that produced President Donald Trump rather than making it about the man himself.

On the ground on Saturday, that vision provided a space for all manner of pet issues and grievances. Signs and chants made statements on immigration, reproductive rights, health care, racism, worker’s rights, Islamophobia, capitalist exploitation, and climate change, often combining several issues or marginalized identity groups in a single sign. Some people may have come to the march to advance a single concern, but far more were there to embrace the whole menu of progressive demands.

Sitting curbside on the National Mall facing the U.S. Capitol building, Krissan Gault told me three generations of her family were there to march for “the fourth generation.” She came from North Carolina to march with her daughter Elle; Gault’s sister and mother came all the way from Washington state and Arizona, respectively. Gault bought her mother’s plane ticket as a 75th birthday present. Their signs spoke to LGBTQ rights, a healthy planet, racial justice, and reproductive rights. “I think everyone here is appreciating everybody else’s issues,” Elle Gault said. “And I’m glad to see so many men here,” her grandmother added.

Christina Cauterucci/Slate

Several major unions, including the Service Employees International Union and AFL-CIO, came to the march in their respective colors. Zahrah Hill, 25, and Symone Holmes, 32, traveled from Chicago with their plumber’s union along with more than three dozen women—carpenters, electricians, bricklayers—from other Chicago trade unions. “It was a no-brainer to come,” Hill said. “We already fight for women’s rights and equality within our trades alone.” The women said their industries are something like 98 percent male, making the march a refreshing reminder that they’re not alone. “It’s about showing your face and letting your voice be heard,” Hill said. “We’re together here in solidarity for sisters everywhere.”

Post-election debriefs in mainstream liberal circles have often turned to the concept of “bubbles”—that most of us live in them, that social media and increasingly ideological news outlets encourage them, and that we need to get out of them if we ever hope to move the country forward. But there are bubbles within bubbles, too, and the bubble of white feminism, as the 53 percent of white women who voted for Trump reminded the rest, has proven particularly hard to pop. Saturday’s march forced all these subgroups together, willingly or not.

White women who would have never chosen to join a Black Lives Matter protest were confronted with hundreds of Black Lives Matter signs and likely found themselves, at least once during the course of the day, in a sea of people chanting the slogan asserting racial justice as a feminist issue. Women who might have come with the ladies’ clubs of their churches saw more pink triangles and rainbow bandannas and “Make America Gay Again” hats than any mass gathering outside a pride parade. Hundreds of thousands of people were pressed ass-to-groin on every street surrounding the Mall—and they may not have chatted up folks outside their friend groups, but they had no choice but to recognize the diversity of needs and issues championed by others in the big tent of feminism.

For Elisa Massimino, 56, that tent covers her opposition to torture and religious bans on entering the country. As president and CEO of Human Rights First, Massimino was marching for justice for refugees. “This marks the beginning of a renaissance, I think, of America standing up for the ideals that make our country strong,” she said.

“So, making America great again?” I asked.

“Judging from today,” she said, scanning the Mall, “it looks pretty great.”

Christina Cauterucci/Slate

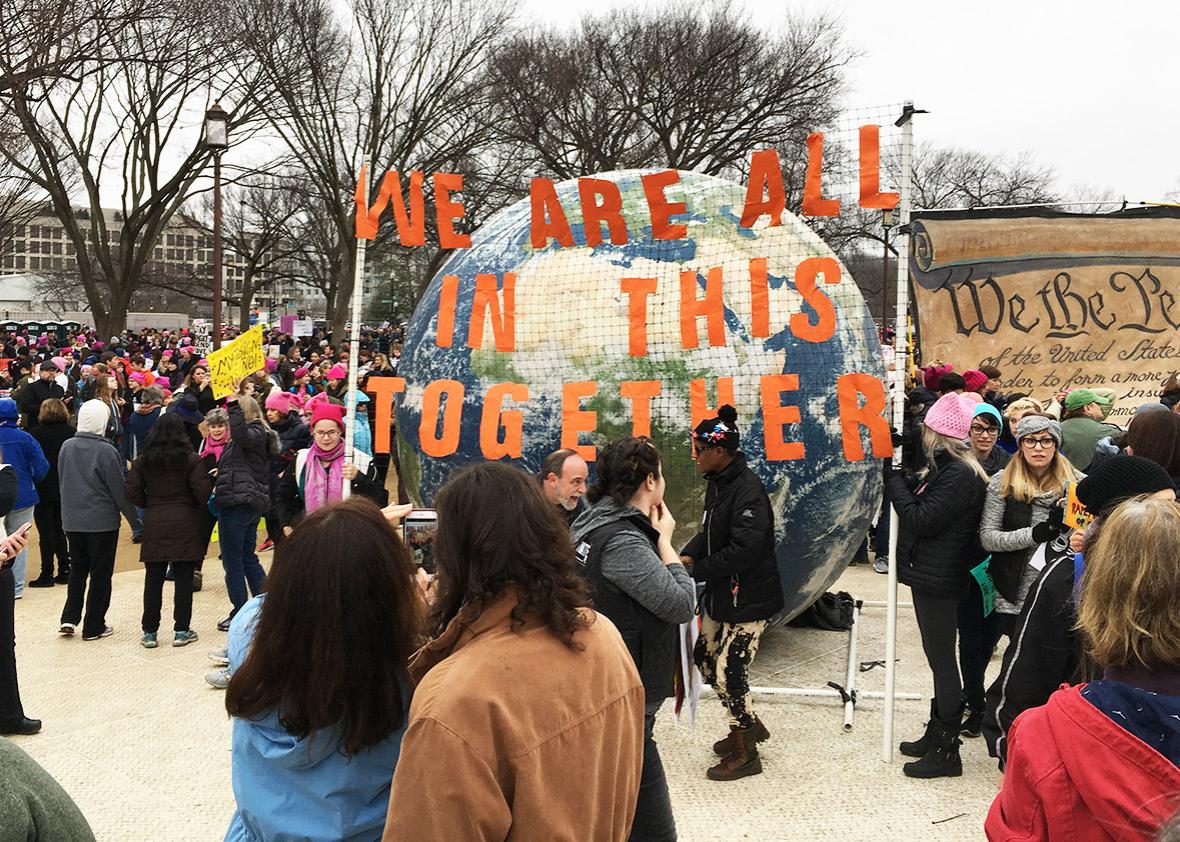

Anyone who didn’t show up hours before the pre-march rally started had no visual or aural clue as to what was happening on the stage a block off the Mall where dozens of celebrities and activists spoke. The vast majority of attendees, oblivious to the carefully curated program, swarmed in gigantic packs on the streets or roamed the Mall as if at a music festival. With several drum circles and the occasional whiff of pot smoke, it sometimes felt like one. (It would have been the most polite music festival in history—I’ve never been called “honey” by so many older women or had so many men apologize for jostling me in passing.) The Backbone Campaign, the activist-support organization that trained the kayakers who stopped an Arctic driller in Seattle, set up shop on the Mall with a gigantic inflated Earth and replica of the Constitution. Executive Director Bill Moyer said the march was the perfect time to engage people who are just starting to get involved in political activism. “It’s important to share skills so people don’t have to reinvent the wheel,” he said. He was handing out fliers to marchers taking photos in front of the Earth and telling them how they could make a similar banner for an overpass, say, with deer netting and other simple materials they could get at a local hardware store.

There were very few, if any, other organizations actively using the march to expand their constituency. I didn’t encounter a single petition or listserv peddler. The closest thing to self-promotion I saw was a representative from Clue, the period-tracking app, asking marchers if they wanted “a free uterus bag.” (It was a tote bag covered in prints of the female reproductive system.) Some groups found other ways to promote their causes. Abortion-rights group Reproaction launched a branded Snapchat filter geotagged to the National Mall. Many other organizations, including Family Values @ Work and EMILY’s List, held satellite events over the weekend, making the event the occasion for a kind of dispersed conference on women’s and progressive issues.

George Washington University graduate students Cristina Hernandez-Guerrero and Morgan Kuster said they hope the march inspires people to go home and effect change in their local communities on whatever issues matter to them. For Hernandez-Guerrero, that’s immigrant rights: Her grandfather was born in the U.S. but was sent back to Mexico illegally in the 1920s. “Us as women have that beauty and power to bring so many issues together in a positive way,” she said.

At another march, a well-meaning attempt at this kind of intersectionality might have yielded a muddled message or a sharp-elbowed mass of nonprofits fighting for visibility and email addresses. But under the big tent of the Women’s March, it all made sense. Unlike single-issue movements that ignore the complex intersections of identities and injustices, the Women’s March leaned into the uncomfortable conversations that conscientious activism requires, leading to controversies over racial politics, abortion rights, and whether or not to honor Hillary Clinton. The platform united the struggles of the people made most vulnerable by Trump’s presidency and the systems of inequality that got him there; the message might have come from women’s mouths, but it was a march for justice of all kinds.

Christina Cauterucci/Slate

The march could prove most galvanizing for the next generation of leaders in politics and advocacy. Kyra Henry, 17, got her New Jersey prep school to organize a bus to the march after she and a few friends decided to go. “I’m here to honor womanhood,” she said. “As a black woman, I feel like in history we’ve been undermined, to say the least, and I think it’s important to be here for representation. Especially this year, it’s nice to see that our words have power.”

Anum, 17, came to the march from Baltimore with her mother, Uzma, and Maya, 11. Anum said their family had been “feeling kind of down” since the election, and when she heard about the march on Facebook last month, she and Uzma thought it would be good to surround themselves with like-minded people. “We wanted to remind ourselves that our country is great and there are people ready to fight against the injustices that are happening,” Anum said. “We’re Muslim, and my mom immigrated from Pakistan, so some of the things Trump said about immigrants and Muslims are really personal to us.”

Uzma said the whole event had her feeling “emotional,” seeing all the people who came out to march for issues that might not directly affect themselves. “That’s the biggest thing I want to give to my daughters,” Uzma said.

At the Women’s March on Washington, her daughters got the message. “I feel so supported just being in this environment, just looking at the posters and everything,” Anum told me. “I think everyone here isn’t here for themselves—they’re here for every single person who’s feeling threatened and afraid.”