Birds That Play Guitar

Courtesy of Ben Mirin

The young male zebra finch alighted on the nearest guitar and bounced across the mahogany fret board. He stumbled on the high E string—it was harder to grip against the polished wood. Then with an inquisitive side-glance, he sang a few bars, stretching his wings, and occasionally breaking off as if awaiting some sort of reply. Then he was finished. He defecated on the frets before uttering a final, insistent nasal call and flitting down to the sand below.

The guitar lay horizontal, propped up by a stainless steel cymbal stand. It had a white finish, perhaps the ideal paint job for concealing the bird droppings that peppered its otherwise gorgeous body. Every time a bird landed, took off, or hopped on its strings, the notes played through a nearby amplifier with preprogrammed digital effects: reverb, overdrive, digital delay.

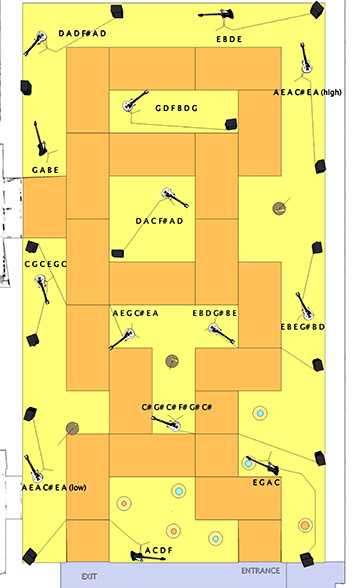

The guitar is one of 14 chromatically tuned rock instruments—10 Gibson Les Pauls, four Gibson Firebirds—wired up inside the Barton Gallery at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass.* They’ve stood there for four months, kept in tune for an orchestra of 70 zebra finches. The birds live in the space, which functions as a temperature-controlled aviary on the museum’s third floor for an exhibit closing on April 13.

Courtesy of Céleste Boursier-Mougenot

The birds’ ghost conductor is Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, a French composer and artist who has become a master at encouraging birds to make music. He does so by creating a kind of musical ecosystem. Called From Here to Ear, this is his 15th installation in a series of works spanning 15 years and cities around the world, from London to Berlin to Milan to Brisbane, Australia. (Click that last city for some amazing looks behind the scenes.)

In every city the exhibit has been wildly popular, and the prevailing question among its visitors has been the same: Do the birds know they’re making music?

“We think they do,” says Trevor Smith, the museum’s curator of contemporary art.

The birds are a mixed-age flock, about half males and half females. Three nest condos are hung from the ceiling, and the floor is covered with sand and patches of tall grass to mimic the finches’ natural environment—Australian grassland. Zildjian cymbals are filled with either water or food.

Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum

As the birds adjusted to the space, the artist adjusted his instruments.

It took about three days to install the guitars, Smith says, and then Boursier-Mougenot “went through roughly a 10-day process of tweaking the sounds, thinking about which notes would come from where, which effects would come from where.”

Boursier-Mougenot calls the installation “a device—a plan. It’s a piece that’s impossible for humans to play.” Instead, the birds are his “flying fingers,” and after his departure the room takes on a life and a rhythm of its own.

Entering the space, your first instinct is to be silent, to stand still as you would while watching a wild animal in its natural habitat. But our interaction with the birds is part of the exhibit.

“The birds are also responding to our presence,” says Smith. “This is the nature of the work. The room is like a three-dimensional score, each of the guitars offers a certain sonic experience, and the birds choose where and how to interact with the room.”

Those choices shift when people walk around the guitars and beneath the aviaries. It’s obvious the birds respond to human presence, but how they react is surprising. Rather than avoiding human visitors, these finches seek them out, showing great curiosity and desire to explore anything new that enters their space.

Courtesy of Brian Barth

All that movement also creates more music. Smith says the birds think of the guitars as musical trees.

“Basically the room is their world now,” Smith said as he walked among the instruments. A female finch alighted on his shoe and he paused before gingerly taking another step. The finch stayed on board, tugging at the seams of his moccasins.

“This is the first time one has ever landed on me,” he whispered excitedly. “It’s pretty cool.”

Zebra finches are incredibly social and curious by nature, and they perform extremely well in Boursier-Mougenot’s orchestrated aviary.

“I am entirely fulfilled by my relationship with the Zebra Finches,” the artist said in an email when asked whether he was considering different birds for future exhibitions. “I don’t exclude the possibility of new partners, but as in all great love stories, it depends in part on the chance encounters life brings along.”

He found the birds currently in residence at the Peabody Essex through a casting company, Animal Actors Inc.

“They’re very social, they’re very musical, they have a very distinct appearance with that orange beak,” Smith says of the finches. “They’re almost like a companion species.”

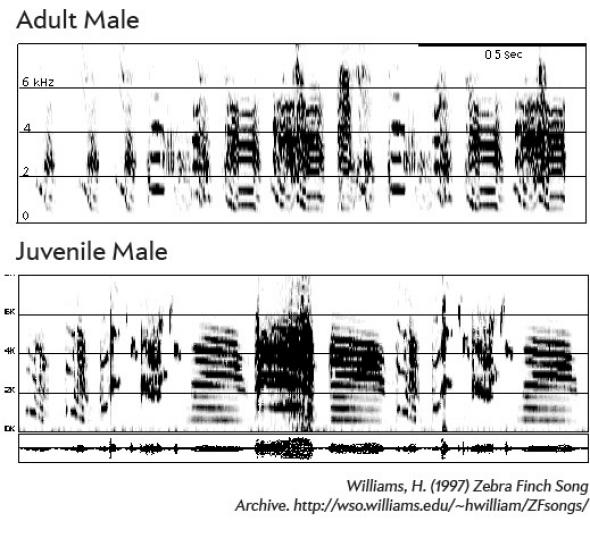

Scientists have long used captive zebra finches to study birdsong, courtship, and brain circuitry. Heather Williams of Williams College in Williamstown, Mass., has worked with the birds for 25 years.

“Zebra finches are perfect for captivity,” she says. “They breed year round. The color green and high humidity trigger their breeding behavior, so in the presence of those elements they can breed continuously.”

There’s certainly a lot of breeding going on in the heat of the Barton Gallery.*

“We dispose of the eggs,” Smith explained. “The finches breed fairly rapidly, so we do what any breeder or pet owner would do that doesn’t want to be overrun by birds.”

What’s really striking is how bird courtship drives the ongoing performance of Boursier-Mougenot’s work. Rather than being deterred or inhibited by the sonic qualities of their environment, it seems as if the birds take ownership of the music as a means of interaction with one another.

“I think they’re perfectly capable of learning the consequences of hopping on one string versus another,” said Williams.

Birds of the same species often develop distinct regional dialects, demonstrating that their songs are not entirely innate but can be molded by what they hear around them. Williams agreed that the presence of actively resonating instruments could easily affect song development in younger males still in the early stages of song development.

“Birds that grow up in cities with a lot of traffic noise tend to develop songs that avoid the traffic noise,” she explained as a point of comparison. “During the learning process these birds develop a song that uses a clear channel.”

Courtesy of Heather Williams/Williams College

In the wild, cutting through the mix can be essential not only for birds looking to attract mates but also for young birds trying to learn their parents’ songs. Williams went on to speculate that the finches could also demonstrate a preference for particular sounds in the exhibit and use them as a basis for imitation and new song composition, as well as adaptations in courtship behavior.

A male sings to a female in a separate cage to the left edge of the video frame. Video courtesy of Heather Williams.

The male birds do a courtship dance that’s coordinated with their song and involves pivoting from side to side and shifting as they move closer to the female. If they hop on certain strings, they could potentially coordinate the sound of the instruments with their overall courtship display.

“I have observed a lot of interesting behavior since January,” said Bradley Benedetti, a museum interpreter who spends hours a day at the exhibit. “I think the males are more interested in looking down at everything, to find a mate, and to keep watch on any competition. I call them scouts. The three guitars in the middle of the space, which only have a distortion effect on them, seem to be where the birds made a connection that they had something to do with the noise. After they made that connection, I noticed their relation to those guitars, and the bass guitars as well, changed.”

At its core, From Here to Ear is a piece of performance art. The environment is totally fabricated, the supply of food and water is constant, and the birds are bred in captivity. There’s even a veterinarian who tends regularly to the flock.

But that doesn’t mean the birds aren’t also behaving naturally. Even as professional animal actors, their resilience and adaptability around electrified instruments, blaring amps, and a stream of human visitors is remarkable. It reflects a successful adaptation that many bird species have made: tolerance to closer proximity with human settlements. It also gives us a chance to see their personalities as visitors to their world.

*Correction, April 10, 2014: This post originally misstated the name of the gallery in which the finches perform.