Congress Is Terrible at Science—and This Should Make Us Worried

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

America’s scientists are nervous. At the American Association for Advancement of Science conference last week, there was much hand-wringing about an “innovation deficit” that threatens science in this country.

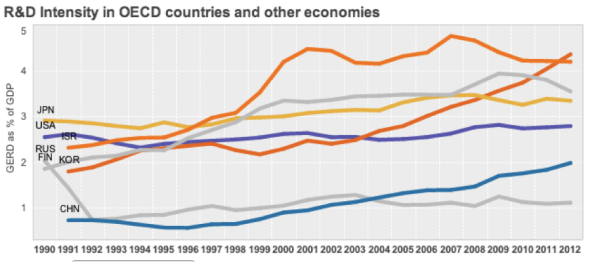

The anxiety is justified. Federal spending for science as a percentage of the government's budget has shrunk in recent decades (from above 10 percent in 1964 to less than 6 percent today).* The private sector isn’t making up the difference. Though companies invest in new science, they tend to emphasize development, rather than research. Funding for “basic research”—studying fundamental scientific questions—has declined in the United States, while in China, it has grown threefold in the last decade. An alarming-looking chart from the OECD compares stagnant overall R&D investment in the United States against the increase seen in other places:

It’s still too early for outright panic. Though research output outside the United States has quickened, much of the science produced elsewhere is replicative work of things first done in the West. The Higgs Boson was discovered at CERN; the 3-D printer commercialized by Americans. In 2013 more than twice the number of patents was filed in the United States than in China (though the prevalence of patent trolls makes this an admittedly imperfect measure of true innovation).

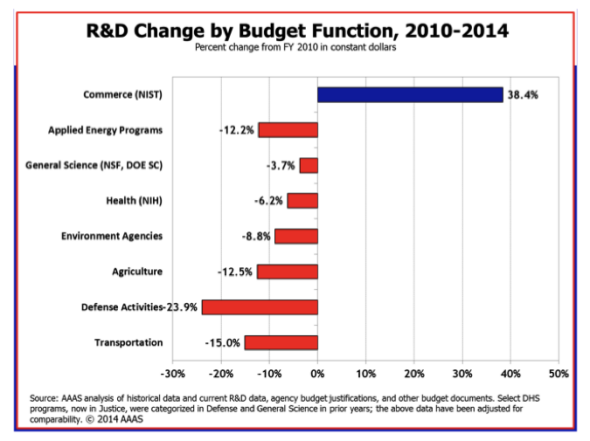

But the trend lines—especially of late—are worrisome. Overall federal R&D funding has fallen by $24 billion since 2010, partly as a consequence of sequestration. The only field of scientific research to receive increased federal funding from 2010 to 2014 is the National Institute of Standards and Technology, an agency in the Department of Commerce. (NIST’s key duty is to set standards for the measurements of things.) The NIH, NSF, and all other research divisions have seen their budgets slashed:

Source: Matt Hourihan, AAAS

For his 2015 budget, President Obama has proposed setting aside $135 billion for science. But this 1.2 percent increase from the 2014 budget doesn’t keep up with inflation. The president wants to prioritize energy, neuroscience, and advanced manufacturing, and for these he has asked for additional funds. But he is “unlikely to get them,” admits Matt Hourihan of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. It is, in the end, a “treading-water budget,” he says.

There are clearly consequences to not funding science adequately. Young would-be physicists can’t get grants to discover more about the universe, so they go into finance to ponder Black-Scholes instead. Though American scientists continue to innovate, up-and-comers are increasingly being lured abroad, laments Hunter Rawlings III, former Cornell president and head of the Association of American Universities, a research-university consortium. If declines in funding continue, American labs may face a brain drain.

More troubling are political hurdles that threaten to limit the possibilities of science itself. There is a preoccupation in government with making science efficient, “justifiable,” immediately deriving “useful results.” Boffins complain that almost as much effort must be put toward proving that their research is “worthwhile” as designing the research itself. A survey found that scientists with federal grant money had to spend 42 percent of their time on administrative reporting.

Congress may make it worse. Frontiers in Innovation, Research, Science and Technology (FIRST), a bill introduced in the House Science Committee in March by Republican Reps. Larry Bucshon and Lamar Smith, proposes a 40 percent cut in the NSF’s social sciences and economics funding, and requires that additional “written justification” be presented for proposed grants.* The NSF would also have to report its justifications for grants to Congress every year. They argue that NSF funds grants for useless research that wastes taxpayer money. The bill’s supporters are making the basic mistake of equating scientific research with spending. It’s clearly not. Economists have found that every 0.5 percent spent on R&D returns 9.5 percent GDP growth. Publicly funded research is particularly fruitful.

Investment comes with risks. It will inevitably be the case that the benefits of some research will not be immediately felt. But increased public funding, and increased public funding in all sorts of scientific endeavors, is a smart risk to take. That’s how you get Smartdust.

*Correction, May 7, 2014: This post originally misspelled Larry Bucshon's last name. Also, this post misstated that federal spending for science as a percentage of GDP has shrunk from 10 percent to 6 percent. Federal spending for science as a percentage of the overall budget has shrunk by this margin.