Deporter in Chief

Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

Cynthia Diaz is an 18-year-old young woman who, beginning April 8, did not eat for six days. She was on a hunger strike in protest of her mother’s detention confinement in an Arizona immigration immigration detention center. She and other hunger strikers have been camped out in front of the White House for two weeks. (Diaz’s hunger strike ended on April 14; others are ongoing.) On a dreary, rain-filled Monday, they held up a banner—“Mr. President Stop Deportations,” it reads—and took turns making speeches in English and Spanish describing the sad tales of deportations that have broken up their families. They were spurred by two hunger strikes begun last month at detention centers in Tacoma, Wash., and Houston.

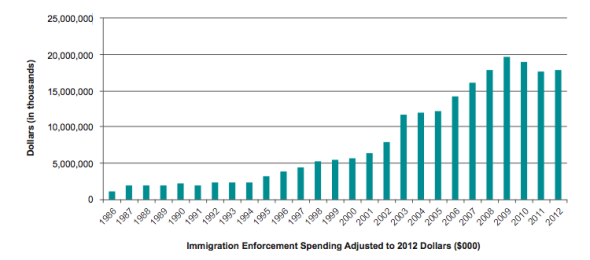

Some 2 million people have been deported during Barack Obama’s presidency. In 2012 there were 369,000 illegal immigrants expelled—a ninefold increase from 20 years ago, the Economist points out. Two factors have made this possible. First, congressional appropriations for law enforcement to carry out deportation have seen a staggering 762 percent rise since 1990. (See the chart from the Migration Policy Institute below.) Congress now authorizes $18 billion to go toward removing people from this country. The budget to carry out all other law enforcement, by contrast, is $14 billion.

Source: Migration Policy Institute

Changes to law have also fed the impetus to deport. Before 1996, immigration judges were given discretion over deportation decisions, but the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act passed that year curbed their freedom to act. Thereafter the law required deportations for particular offenses, regardless of context, that could be applied retroactively. If a man who did not have his immigration papers in order misfiled his taxes in the 1970s, he could be deported in 1996 for having committed an “aggravated felony,” a severely punished offense specifically reserved for illegal immigrants. Then in 2007, Congress mandated that Immigration and Customs Enforcement must maintain 34,000 beds at the 255 detention centers around the country where it holds people awaiting possible deportation. That was an implicit invitation to fill them, says Kamal Essaheb of the National Immigration Law Center—as deportations have gone up, the number of those awaiting them have, too.*

Until last month, the administration has insisted that it has no choice but to enforce these laws. It has done so with apparent zeal. In 2008 ICE enacted the Secure Communities program, whereby a brush with the law means your fingerprints are sent not only to the FBI (the long-standing precedent) but also to the Department of Homeland Security. That creates an opportunity to simultaneously check for a chance to deport. A study from Syracuse University last week suggests that the program has largely resulted in deportations of noncriminal aliens, rather than people engaged in illicit activities.

As hope for immigration reform has lagged, calls for the president to change draconian enforcement practices have increased. In March, Obama ordered a review of DHS deportation practices. But this doesn’t go far enough. There are easy things the president could do to relieve the strain of expulsion where it does little good. Essaheb points out, for example, that systematic use of humanitarian parole, which gives reprieves to those who have been barred entry, could be granted for separated families. Adding adults to the 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals memorandum, which directed ICE to exercise discretion for deportation of those who arrived as children, might alleviate the danger of deportation for some who are threatened by it.

But the hunger strikers on the president’s doorstep will likely remain disappointed. After a number of meetings with immigration advocate groups over the past months, the White House announced Tuesday that it thinks that the burden to reform immigration should be left to Congress after all.

Update, April 18, 2014: The president yesterday took questions on immigration. He reiterated that DHS is reviewing its practices, and said that it “should not be in the business necessarily of tearing families apart.” His remarks can be found here.

*Correction, April 17, 2014: This post originally misspelled Kamal Essaheb's last name.