The Climate-Controlled Shipping Containers That Transport Our Food Are Called Reefers

Courtesy of Håkan Dahlström/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about shipping containers—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

There are around 6,000 cargo vessels out on the ocean right now, carrying 20 million shipping containers, which are delivering most of the products you see around you. And among all the containers are a special subset of temperature-controlled units known in the global cargo industry—in all seriousness—as reefers.

Seventy percent of what we eat passes through the global cold chain, a series of artificially cooled spaces, which is where the reefer comes into play.

Prior to the rise of mass containerization, cooled goods on bulk cargo ships were stored together in a single space. That zone could be kept at just one temperature, so it could only carry one product at a time.

Courtesy of Hocken Library/Wikimedia Commons

When goods arrived in port, the local economy would be flooded with that single commodity, be it fresh produce or frozen meat. Prices dropped, food was wasted, and consumers got fed up with eating too much of one product at a time.

Containers in general, but especially the intermodal variety, were pioneered by trucker Malcolm McLean, and they changed the shipping game forever. Intermodal boxes were built to move by various forms of transit, able to be easily picked up from ships and dropped on trucks or trains without loading or unloading the contents. Goods moved faster, and costs were reduced, as fewer workers were required throughout the process.

For dry goods (those needing no refrigeration) the standard shipping container made transport easier right from its start. For goods needing temperature-controlled environments, the situation was more complex, as early refrigerated containers yielded mixed results.

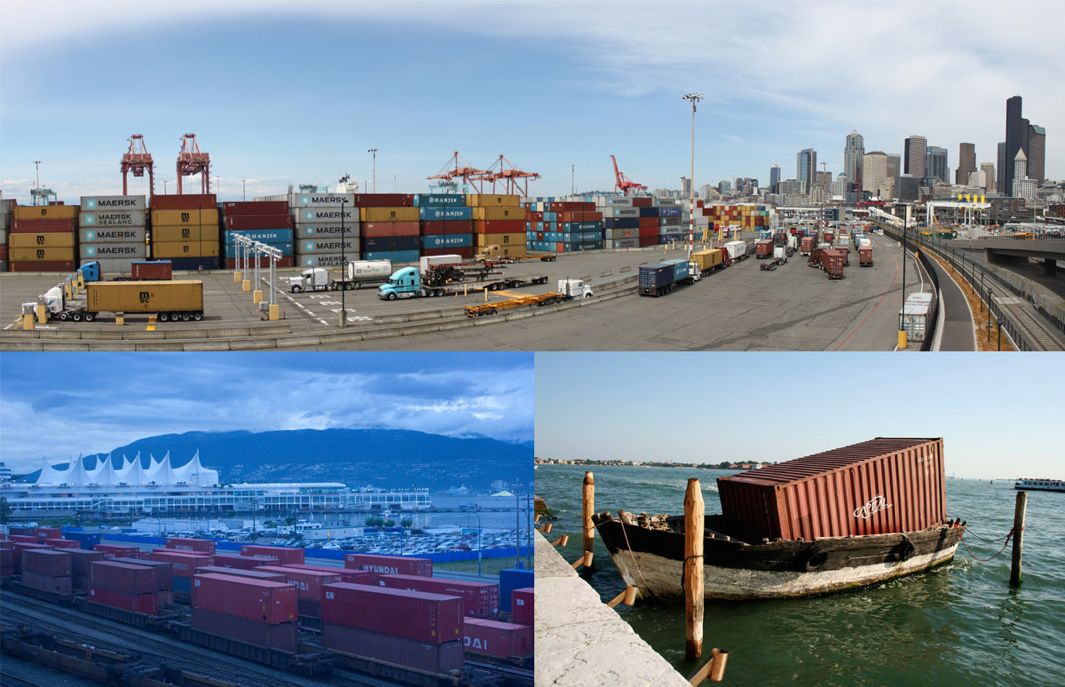

Courtesy of SounderBruce, Roland Tanglao, and Claudio/Flickr

No one knew why some shipments of perishable goods made it through to their destination ports unscathed, while other shipments were partially or entirely rotted or, conversely, frozen solid. Companies would pack tons of produce into refrigerated containers, send them on their way, and effectively hope for the best.

A refrigerated shipping container used to be like a scientific black box, where only inputs and outputs were observed. Shipping companies made efforts to tweak temperatures and rearrange goods inside the containers, but ports on the receiving end still opened containers full of frozen or spoiled fruits and vegetables. The reefers needed some additional analysis, and shipping companies needed some way to keep tabs on goods in transit.

Thus, before it was cool to convert cargo containers into habitable architecture, some scientists created their own mobile laboratory inside a shipping container. This research lab had to be transported alongside cargo-filled containers as they made their way through the supply chain, from train to truck to ship. Installing the lab within a container was a natural choice.

Courtesy of Ruth Hartnup/Flickr

One of these scientists, Barbara Pratt, is now the head of reefer services for Maersk, but in the 1970s she was a recent college graduate commissioned by General Foods to study container refrigeration. For seven years, she traveled with a 40-foot converted steel box workspace that contained a giant computer, as well as a shower, microwave, bunk beds, and, of course, a refrigerator.

The container lab connected to the other cargo containers on the ship with 150 sensors on the ends of salt-resistant cables. These cables connected to the giant computer and monitored temperature, humidity levels, and gas concentrations of the goods in transit.

On ships, Pratt and her colleagues would stay in crew quarters, but they would cycle through the lab regularly, sometimes sleeping in their container alongside the computer.

As it turns out, a good reefer doesn’t just keep a consistent temperature—it also regulates airflow and controls internal atmosphere. The results of Pratt’s research impacted every aspect of shipping by reefer, from how goods are packed to how cool air is pumped into containers (from below rather than above).

The industry has continued to evolve in the decades since Pratt’s stint cruising the world on cargo vessels, and many innovations have grown out of her work. In today’s high-tech containers, the process of ripening fruit can now be slowed down or sped up, timed to coincide with the dates on which produce will hit the supermarket shelves. Even fragile goods (like fish and flowers) are regularly sent inside these precisely controlled reefers.

There is no doubt that containers have revolutionized the way we ship and consume goods around the world. While locavores may lament the globalization of food and associated environmental implications, the global shipping industry, Pratt argues, encourages us to eat more healthily. In many climates, fresh fruits and vegetables would not be available year-round without the artificial cryosphere: the vast global networks of refrigerated shipping and storage spaces. For better or for worse, reefers are an integral part of our modern existence.

Courtesy of Steven Straiton/Flickr

Meanwhile, for some containers, shipping is still not quite the end of the story. The globally standardized shipping module has inspired some fresh architectural applications, and reefers in particular are ideal candidates for adaptive reuse, as they are already insulated and designed around airflow.

Steel containers, while robustly constructed, are inevitably damaged and even slightly defective units are generally removed from the supply chain. Containers also tend to pile up in places with more imports than exports (aka the West), so it’s often easier for companies to offload old containers locally than to ship them back empty.

As a result, industrious individuals and professionals have converted surplus containers to homes, offices, schools, and more. In turn, ancillary industries have sprouted to support this movement, supplying standardized ways to connect containers with utilities and otherwise modify them for alternative uses.

Some architects have taken to specializing in containerized dwellings, offering container-specific prefab plans and design services. In their second lives on land, human-habitable containers still raise questions of temperature control; even now, there may be more to learn from Pratt’s time in a shipping container at sea.

Courtesy of m-louis/Flickr

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.