The Tiny Deep Sea Capsule That Changed Our Understanding of Marine Life

Photo by Mike Cole/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about the Bathysphere—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

In 1860, a chance find at sea forever changed our understanding of marine habitats, sparking an unprecedented push to explore a new world of possibilities far below the surface of our planet’s oceans. Deep sea life, previously thought possible down to a maximum depth of 1,800 feet, was found in the form of creatures attached to a transatlantic telegraph cable.

Raised for repair from its resting place some 6,000 feet down on the ocean floor, the line was covered with marine species. This paradigm-shifting revelation sparked the public’s imagination, fueled global scientific research, and propelled the eventual development of new submarine vessels, including the record-breaking Bathysphere.

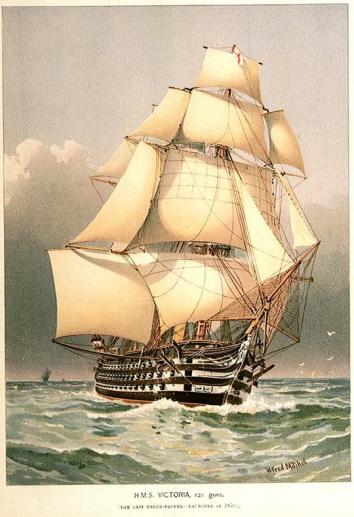

Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum/Wikimedia Commons

In the years following the telegraph cable find, subsequent attempts were made by surface vessels, including a global deployment of the HMS Challenger, to net additional creatures from the deep. Many of these specimens could not, however, physically withstand the change in pressure, effectively exploding as they were raised.

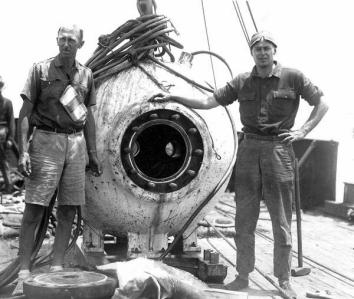

Finally, in the 1920s, ornithologist William Beebe and engineer Otis Barton teamed up to create the Bathysphere, a pressurized submersible that ultimately would take them more than 3,000 feet down, six times deeper than any previous vessel. The key to the Bathysphere’s success was a spherical shape and pressurization.

Launched from a science station on Nonsuch Island, Bermuda, the Bathysphere was far from the first attempt of its kind. Unpressurized subsurface vehicles had been built hundreds of years prior. Diving bells, which trap surface air for underwater excursions and treasure hunting, date back thousands of years. Many of these were actual church bells; lowered into the water by a boat, they stored pockets of air underwater, allowing divers to reach greater depths. Even Alexander the Great is reported to have explored the oceans inside a sort of proto-Bathysphere.

But the most critical factor limiting humans from the ocean’s depths was the pressure that would cause lungs to collapse and submarines to be crushed. The Bathysphere, a pressurized sphere with a thick metal hull and fused-quartz windows, would provide protection.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Wikimedia Commons

Little was included in the Bathysphere beyond the bare essentials: oxygen tanks, chemical scrubbers, a spotlight, and a telephone line—basics for survival, exploration, and communication. The Bathysphere’s hatch had to be bolted into place each time, and personal cooling was accomplished with hand-waved palm fronds. In the absence of even a flat surface to sit or stand on, the Bathysphere was a crowded place for the pair of explorers it transported, invariably forcing them uncomfortably close together.

As the intrepid William Beebe and Otis Barton pushed ever further below the surface, the stakes were raised, and the dangers increased. Even a small leak in the hull could cause a jet of water to shoot into the Bathysphere with the force of a bullet. The rewards, however, encouraged the duo to take the risk. They went deeper and deeper, discovering more and more forms of life.

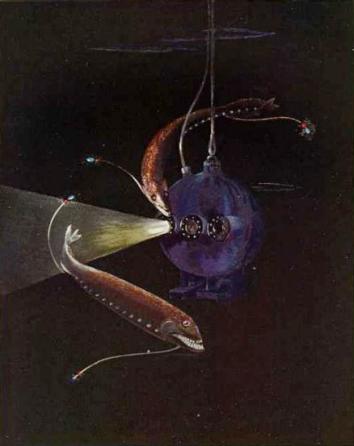

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Beebe and Barton pressed the limits of their submersible, eventually reaching a record depth of 3,028 feet. These depths have since become known as the Bathyal Zone. Using telephones, the duo would describe the sea life surrounding them to the vessel above. There, illustrator Else Bostelmann would turn their observations into detailed drawings, many of which were subsequently published in National Geographic and circulated around the globe.

For years to come, many would look at the resulting drawings in disbelief, convinced that Beebe and Barton were lying about what they had seen. However, their observations would eventually be confirmed by other scientists and seekers. The adventures of the Bathysphere kick-started a wave of additional submarine development and deep sea exploration, culminating in a successful journey in 1966 by the Trieste to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest in the world at more than 35,000 feet. Today, the Bathysphere remains on display at the New York Aquarium at Coney Island.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.