Air France Flight 447 and the Safety Paradox of Automated Cockpits

Courtesy of Pawel Kierzkowski/Wikimedia Commons

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about the safety paradox of airplane automation—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

On the evening of May 31, 2009, 216 passengers, three pilots, and nine flight attendants boarded an Airbus A330 in Rio de Janeiro. This flight, Air France 447, was headed across the Atlantic to Paris. The takeoff was unremarkable. The plane reached a cruising altitude of 35,000 feet; passengers read, watched movies, and slept. Everything proceeded normally for several hours. Then, with no communication to the ground or air traffic control, Flight 447 suddenly disappeared.

Days later, several bodies and some pieces of the plane were found floating in the Atlantic Ocean. But it would be two more years before most of the wreckage was recovered from the ocean’s depths. All 228 people on board had died. The cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorders, however, were intact, and these recordings told a story about how Flight 447 ended up in the bottom of the Atlantic.

The story they told was about what happened when the automated system flying the plane suddenly shut off, and the pilots were left surprised, confused, and ultimately unable to fly their own plane.

The first so-called autopilot was invented by the Sperry Corp. in 1912. It allowed the plane to fly straight and level without the pilot’s intervention. In the 1950s the autopilot improved and could be programed to follow a route.

By the 1970s, even complex electrical systems and hydraulic systems were automated, and studies were showing that most accidents were caused not by mechanical error but by human error. These findings prompted the French company Airbus to develop safer planes that used even more advanced automation.

Airbus set out to design what it hoped would be the safest plane yet—a plane that even the worst pilots could fly with ease. Bernard Ziegler, senior vice president for engineering at Airbus, famously said that he was building an airplane that even his concierge would be able to fly.

Not only did Ziegler’s plane have autopilot, it also had what’s called a fly-by-wire system. Whereas autopilot just does what a pilot tells it to do, fly-by-wire is a computer-based control system that can interpret what the pilot wants to do and then execute the command smoothly and safely. For example, if the pilot pulls back on his or her control stick, the fly-by-wire system will understand that the pilot wants to pitch the plane up, and then will do it at just the right angle and rate.

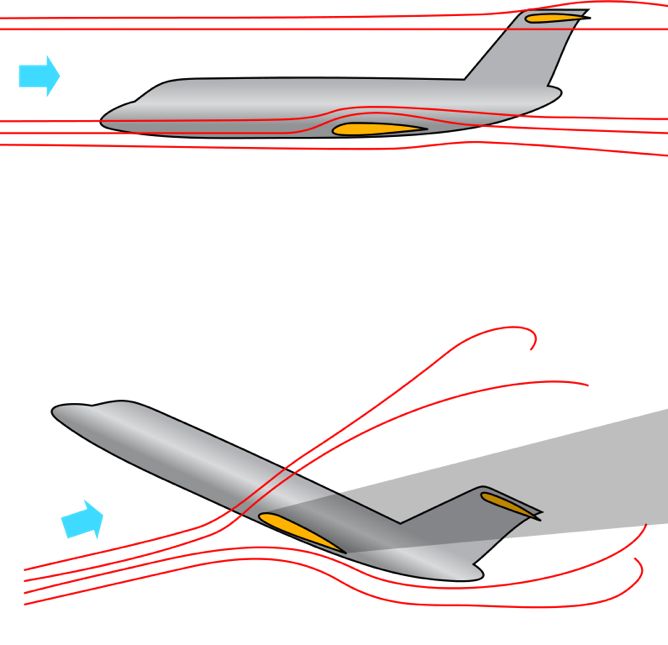

Importantly, the fly-by-wire system will also protect the plane from getting into an aerodynamic stall. In a plane, stalling can happen when the nose of the plane is pitched up at too steep an angle. This can cause the plane to lose lift and start to descend.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Stalling in a plane can be dangerous, but fly-by-wire automation makes it impossible—as long as it’s on. Unlike autopilot, the fly-by-wire system cannot be turned on and off by the pilot. However, it can turn itself off. And that’s exactly what it did as Flight 447 made its trans-Atlantic flight.

When a pressure probe on the outside of the plane iced over, the automation could no longer tell how fast the plane was going, and the autopilot disengaged. The fly-by-wire system also switched into a mode in which it was no longer protecting against aerodynamic stall. When the autopilot disengaged, the co-pilot in the right seat put his hand on the control stick—a little joysticklike thing to his right—and pulled it back, pitching the nose of the plane up.

This action caused the plane to go into a stall; yet, even as the stall warning sounded, the pilots couldn’t figure out what was happening to them. If they’d realized they were in a stall, the fix would have been clear. “The recovery would have required them to put the nose down, get it below the horizon, regain a flying speed and then pull out of the ensuing dive,” says William Langewiesche, a journalist and former pilot who wrote about the crash of Flight 447 for Vanity Fair.

The pilots, however, never tried to recover, because they never seemed to realize they were in a stall. Four minutes and 20 seconds after the incident began, the plane crashed into the Atlantic, instantly killing all 228 people on board.

Courtesy of Mysid/Wikimedia Commons

There are various factors that contributed to the crash of Flight 447. Some people point to the fact that the Airbus control sticks do not move in unison, so the pilot in the left seat would not have felt the pilot in the right seat pull back on his stick, the maneuver that ultimately pitched the plane into a dangerous angle. But even if you concede this potential design flaw, it still raises the question: How could the pilots have a computer yelling “stall” at them and not realize they were in a stall?

It’s clear that automation played a role in this accident, though there is some disagreement about what kind of role it played. Maybe it was a badly designed system that confused the pilots, or maybe years of depending on automation had left the pilots unprepared to take over the controls.

“For however much automation has helped the airline passenger by increasing safety it has had some negative consequences,” says Langewiesche. “In this case it’s quite clear that these pilots had had experience stripped away from them for years.” The captain of the Air France flight had logged 346 hours of flying over the preceding six months. But within those six months, there were only about four hours in which he was actually in control of an airplane—just the takeoffs and landings. The rest of the time, autopilot was flying the plane. Langewiesche believes this lack experience left the pilots unprepared to do their jobs.

Complex and confusing automated systems may also have contributed to the crash. When one of the co-pilots pulled back on his stick, he pitched the plane into an angle that eventually caused the stall. But it’s possible that he didn’t understand that he was now flying in a different mode, one that would not regulate and smooth out his movements. This confusion about how the fly-by-wire system responds in different modes is referred to, aptly, as “mode confusion,” and it has come up in other accidents.

“A lot of what’s happening is hidden from view from the pilots,” says Langewiesche. “It’s buried. When the airplane starts doing something that is unexpected and the pilot says ‘Hey, what’s it doing now?’—that’s a very very standard comment in cockpits today.”

Langewiesche isn’t the only person to point out that “What’s it doing now?” is a commonly heard question in the cockpit. In 1997, American Airlines Capt. Warren VanderBurgh said that the industry has turned pilots into “children of the magenta” who are too dependent on the guiding magenta-colored lines on their screens. Langewiesche concurs: “We appear to be locked into a cycle in which automation begets the erosion of skills or the lack of skills in the first place and this then begets more automation.”

However potentially dangerous it may be to rely too heavily on automation, no one is advocating getting rid of it entirely. It’s agreed upon across the board that automation has made airline travel safer. The accident rate for air travel is very low: about 2.8 accidents for every 1 million departures. (Planes made by Airbus, by the way, are no more or less safe than those from its main rival, Boeing.)

Langewiesche thinks that we are ultimately heading toward pilotless planes. And by the time that happens, the automation will be so good and so reliable that humans, with all of their fallibility, will really just be in the way.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.