How Freud’s Couch Became a Pop-Culture Phenomenon

Courtesy of Robert Huffstutter/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about Freud’s couch—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

In 1889 Sigmund Freud was still relatively new in his field, or what we’d call pre-Freudian Freud. At 33 years old, working as an assistant to another psychiatrist, he hadn’t had any of his big ideas yet.

Freud was mostly practicing hypnosis, which was a cutting-edge but controversial treatment. One day Freud gets a new patient, a very wealthy woman named Fanny Moser. Moser was struggling from all kinds of ailments—hysteria, sleeplessness, pain, and odd tics, and she had lots of doctors. When Moser came to Freud, he would have her lie down on a couch, just like he did with his other patients. A lot of hypnotists used couches to get patients into a more relaxed state, but Freud especially needed it because he was kind of a clumsy hypnotist.

Freud would tell Moser, “You’re very getting sleepy,” and she would insist that, no, in fact, she wasn’t. Instead, Moser wanted to talk. At first Freud would interrupt her with his theories, but she wasn’t having it. She wanted to tell him her stories. That’s when the light went on. Freud realized that if you just let patients talk and don’t say anything, they will let down their defenses, and the unconscious will be revealed. This is the moment when the pre-Freudian Freud becomes the Freudian Freud. The Freudian Freud’s new techniques and theories for therapy would come to be called “psychoanalysis,” and it would be embodied, in practice and popular culture, by a single piece of furniture: the couch.

Courtesy of Ann Hepperman

You can actually go visit Freud’s couch, which is on display in his last home in London. Freud had the couch shipped from Vienna after fleeing the Nazis in 1938. Freud saw patients on his couch right up to his death a year later. Freud actually had a few couches, but the one we now associate with him was a gift from a patient, a Madame Benvenisti. She told Freud that if she was going to have her head examined, she might as well be comfortable, so she bought him a plain, beige, divan-style sofa—what some people might call a “swooning couch”—which Freud covered in exotic red Persian carpets and piled up with velvet pillows.

The more patients Freud saw on the couch, and the more he wrote about those patients, the more the couch became thought of as an essential instrument in Freudian psychoanalysis. The couch became a tool to help patients lie down on their backs and look up at the ceiling, which forced them to look into themselves rather than, say out a window or into the face of the analyst. The analyst typically sat in a chair, out of sight from the patient on the couch. Some analysts believe this positioning helps the patient feel freer to open up, but Freud, however, may have had more selfish reasons. He once remarked: “I cannot put up with being stared at by other people for eight hours a day.”

In any case, the couch took on such a central role in psychoanalytic practice that it started to mean good business for analytic couch manufacturers. Imperial Leather Furniture Company in Queens, New York, sold psychoanalytic couches like hot cakes starting in the 1940s.

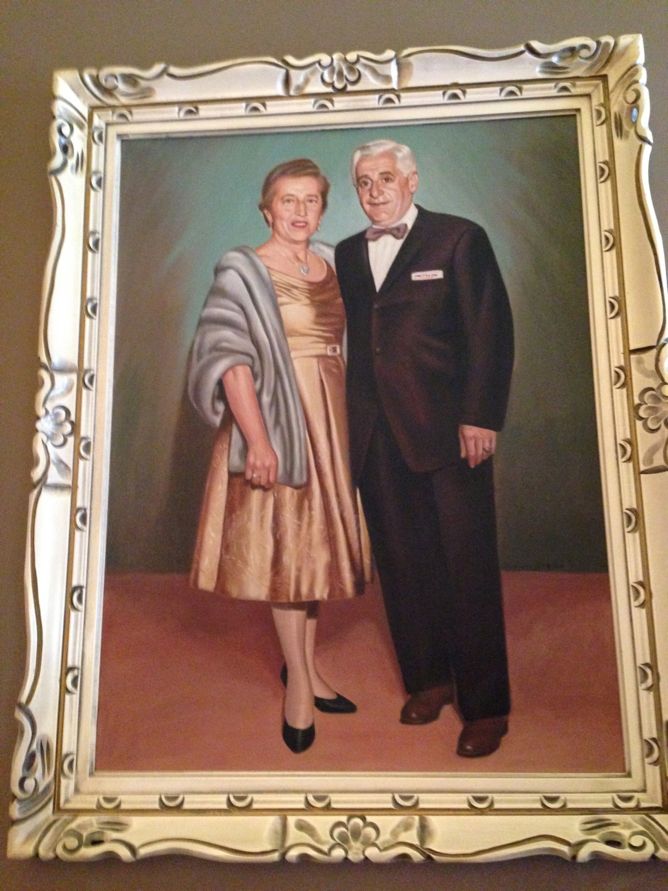

Courtesy of Ann Hepperman

Irving Levy patented a version of a psychoanalytic couch he’d designed with his business partner. Alicia Brafman, Levy’s daughter, says he was extremely proud of his couch design. Every time anyone walked into the store, he’d saunter up and say, “You know we make Freud’s couches.” Which of course, he didn’t. The couch he sold didn’t look anything like Freud’s exotic, cozy pile of cushions. These were sleek; low to the ground; and free of buttons, cushions, and accessories that nervous patients could pick at.

The Imperial Leather Furniture Company boomed in the ’40s, ’50s, and early ’60s, which some have called the golden age of psychoanalysis. Then in the late ’60s, things changed. People started to experiment with alternative therapies, and the first generation of antidepressants offered faster relief. Traditional psychoanalysis fell out of favor. Analytic couch sales declined. But you wouldn’t know it from popular culture.

Even though real therapists aren’t using the couch all that much, cartoonists still need it. Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor of the New Yorker, says the couch is fantastic as a symbol. It’s just what a joke needs. “I think the couch immediately establishes the power relationships here,” says Mankoff. “The psychiatrist is in control.”

It’s not just in the New Yorker. You see the couch all over popular culture. In the Sopranos, Tony Soprano spends a lot of time with his therapist. And even though he always sits in a chair, when the camera pans out, there’s a very typical brown analytic couch in the background, as if the set designer wanted to reassure our subconscious about what he was doing there.

All those different iterations of the couch have compelled thousands of people to make the pilgrimage to see the original couch in London. The couch exemplifies how Freud revolutionized our understanding of the human mind. Freud has given us the id, the ego, the superego, the Freudian slip, and a whole number of complexes, but beyond creating a vocabulary for the brain, he gave it a place to rest. To feel at ease. To lie down and talk.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.