How Apple’s User-Friendly Design Doomed the Computer Mouse’s Complex Cousin

Courtesy of the Doug Engelbart Institute

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about an alternative to the computer mouse—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

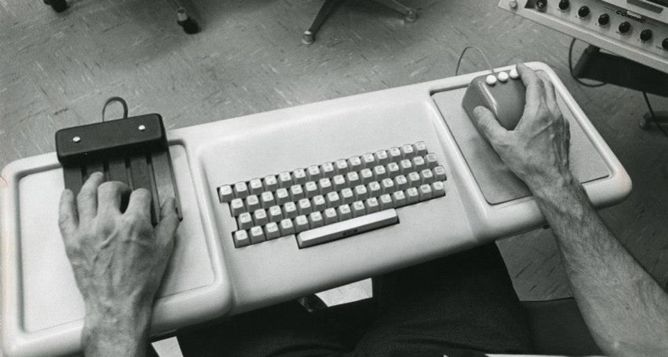

If you are looking at a computer screen, your right hand is probably resting on a mouse. To the left of that mouse (or above, if you’re on a laptop) is your keyboard. As you work on the computer, your right hand moves back and forth from keyboard to mouse. You can’t do everything you need to do on a computer without constantly moving between input devices.

There is another way.

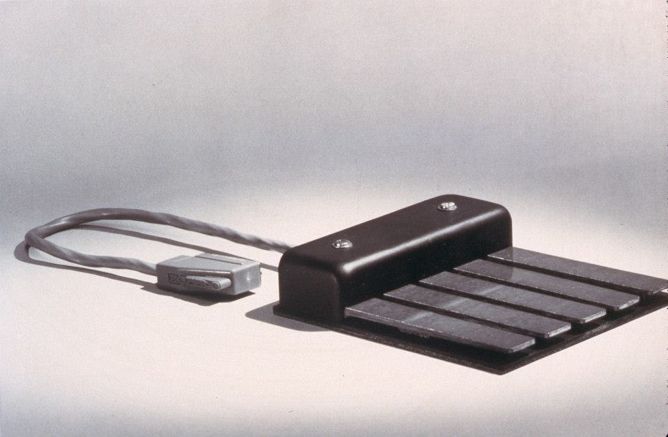

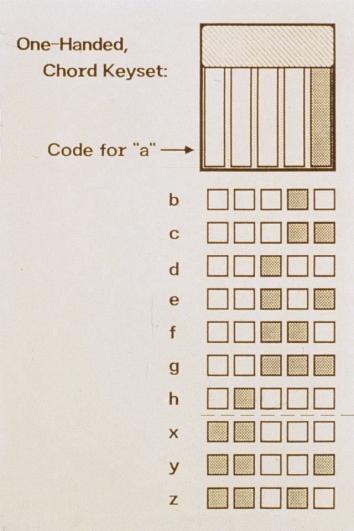

A device called a “keyset” could help you navigate virtual environments without moving your hands back and forth. With the mouse in your right hand, the keyset would occupy your left hand. Its five buttons resembled piano keys.

Courtesy of SRI International and Christina Engelbart

Used in tandem with a mouse (specifically, a three-button mouse), the keyset enabled the user to type out all the characters of the alphabet and execute shortcut commands. The keyboard, thus, would be secondary—perhaps even irrelevant—meaning users could keep their eyes their screens and not glance down at their fingers.

This could be the way of the future. But it’s actually the way of the past.

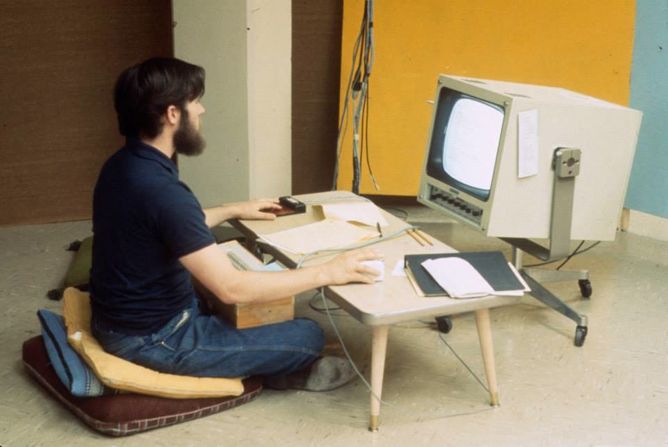

Courtesy of SRI International and Christina Engelbart

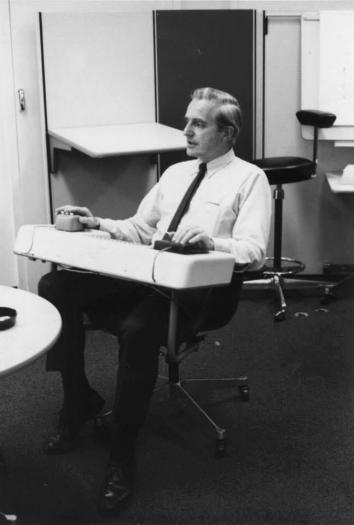

Doug Engelbart invented the keyset in the 1960s. Engelbart was also the person who invented the mouse.

Engelbart’s first mouse was a block of wood about the size of three decks of cards stacked on top of one other. It pivoted atop a metal wheel and had three buttons.

Not satisfied merely pointing and clicking, Engelbart imagined that his mouse would be used in combination with a keyset to execute all kinds of commands that today are difficult to imagine doing without a keyboard.

Courtesy of Luisa Beck

Take word processing, for instance. The five-button keyset could produce all 26 letters by memorizing combinations of these keys used together. Learning to type would take a lot of practice, but Engelbart believed that with lots of repetition, the muscle memory would take over.

While Engelbart realized that learning the keyset was difficult, ease of use wasn’t the top priority. He wanted the computer inputs to be as powerful as possible, and that required some complexity. He imagined that consumers would learn how to use the mouse and keyset slowly over time, like how one learns to operate a car.

The virtuosity and discipline required for Engelbart’s mouse and keyset illustrate his larger ideas about what computers had the potential to do. Engelbart thought computers could help us communicate and collaborate—a total departure from how most engineers thought of computers in 1950s, which was just as giant calculators.

Courtesy of SRI International and Christina Engelbart

In the early 1960s, Engelbart got funding to start his own lab. His team of researchers started building entire online collaboration systems and experimenting with video conferencing, collaborative text editing, outlining tools, hyperlinks, and devices such as the mouse and keyset.

These complicated ideas weren’t particularly popular or marketable, and by the late 1970s, Engelbart’s team ran out of funding to continue their research. Many of Engelbart’s researchers migrated to Xerox PARC (one of the most cutting-edge computing research institutes in its time), as did many of Engelbart’s prototypes.

And that’s how, in 1979, Steve Jobs first saw the mouse (and keyset) while visiting PARC.

Although Jobs found the mouse-and-keyset setup intriguing, he thought it was way too complex. Jobs believed that computers should be as simple and user-friendly as possible. Per Jobs’ directive, Apple’s version of the mouse would have only one button.

Apple never even considered including Engelbart’s keyset in the early personal computers. The keyset was too costly, clunky, and complicated; Jobs knew that consumers didn’t want to buy computers they’d have to learn how to use over the course of many months. Jobs wanted customers to come into Apple stores, look at their products, try them out, figure them out in the first few minutes, and buy them immediately. Even today, Apple products are so simple that a toddler can operate them perfectly.

Courtesy of SRI International and Christina Engelbart

Engelbart used to compare the sleek, simplified Apple products to a tricycle. You don’t need any special training to operate a tricycle, and that’s fine if you’re just going to go around the block. If you’re trying to go up a hill or go a long distance, you want a real bike. The kind with gears and brakes—the kind that takes time to learn how to steer and balance on.

Engelbart thought that because the consumer market prioritizes simple and user-friendly devices over more complex and “learnable” devices, it has only been selling us tricycles. Although, without people like Jobs, perhaps only a few people would be on bikes, and the rest of us would be too intimidated to get on wheels at all.

Though the ease-of-use paradigm has mostly won out, Engelbart’s philosophy continues to influence technologists today. A device called a monome—used mostly for music—is complex enough that even its creators haven’t totally mastered it.

The best design may be the one that gives us a clear path to learning if we choose to. Put another way, designs that helps us transition from tricycle-riding to bicycle-riding, so that if we want, we can choose to go up some really big hills.

Courtesy of SRI Internationaland Christina Engelbart

For this episode, producer Luisa Beck spoke with Christina Engelbart, executive director of the Doug Engelbart Institute, and Larry Tesler, who worked at Apple from 1980 to 1997 as vice president and chief scientist.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.