Penn Station Wasn’t Always the Laughingstock of New York City

Courtesy of Erwin Bernal/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about New York City’s Penn Station—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

New Yorkers are known to disagree about a lot of things. Who’s got the best pizza? What’s the fastest subway route? Yankees or Mets? But all 8.5 million New Yorkers are likely to agree on one thing: Penn Station sucks.

There is nothing joyful about Penn Station. It is windowless, airless, and crowded. Some 650,000 people suffer through Penn Station on their daily commute—more traffic than all three of the New York area’s major airport hubs combined.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Hatred of Penn Station manifests itself in popular culture; in Broad City, Abbi Jacobson’s character gets dumped because her boyfriend would rather end their relationship than enter Penn.

Though Penn Station is a drab, low-ceilinged rat maze of a station, it used to be the opposite. It was vast, light-filled, and gorgeous.

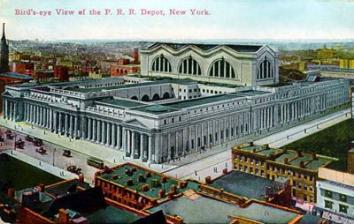

It was the fourth-largest building in the world when it was finished.

The original Penn Station in New York City opened in 1910. It was majestic. Travelers would enter through an exterior facade of massive Doric columns. Inside was a grand staircase into a waiting room not unlike a Roman temple. It was a Parthenon for trains.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The old Penn Station was the brainchild of Alexander Cassatt, head of the Pennsylvania Railroad. For Cassatt, Penn Station would fix a problem that had plagued New York for years—getting between Manhattan and New Jersey. At the time, passengers could only get across the Hudson River via ferry. Cassatt built the first-ever train tunnel to run underneath the Hudson River, which was considered one of the greatest engineering feats of all time.

The grandeur of Penn Station would thus crown his monumental achievement. Newspapers called it the eighth wonder of the world. Everyone loved it.

Courtesy of the New York Public Library/Flickr

Everyone, that is, except for one other railroad family that owned another station across town.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Vanderbilt family owned Grand Central Terminal, which was not anywhere near as “grand” as it is now. Not wanting to be outdone by the beauty and grandiosity of Penn Station, the Vanderbilts tore down their Grand Central and built a newer, shiner, Beaux Arts–style Grand Central Terminal. This is the one we know today.

Courtesy of Eric Baetscher/Wikimedia Commons

Penn Station was only 40 years old at this point, but its glory days were already numbered. After World War II, passenger trains just weren’t as popular anymore. The Pennsylvania Railroad Co. couldn’t afford the upkeep of Penn Station’s grandeur. Its glory gave way to grime.

Pennsylvania Railroad executives knew that they could profit if they could rent out the space above the station to a big, tall building. There were proposals to build parking garages, amphitheaters, and a 40-story office tower. But the one that won out was the futuristic sports and entertainment palace—Madison Square Garden.

A deal was struck: Pennsylvania Railroad would keep the train tracks in place and sell the air rights above them. Penn Station would be demolished in the process.

Courtesy of New York Architecture

The only New Yorkers who seemed to care about the destruction of Penn Station were a small group of activist architects who called themselves AGBANY—the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York.

On Aug. 2, 1962, 200 architects marched up and down Seventh Avenue shouting slogans like “Polish don’t demolish!” and “Save our heritage!” The men wore suits; the women wore white gloves and pearls. The lettering on their signs was impeccable. But demolition continued on schedule.

A year later, on Oct. 28, 1963, jackhammers tore into Penn Station’s granite slabs. The demolition took about three years. By 1966, most of Penn Station’s remains—the Doric columns, the granite and travertine details—had been dumped in a New Jersey swamp.

Courtesy of Szapucki/Flickr

The new Penn Station was summarily hated by everyone. In 1968, architectural historian Vincent J. Scully famously remarked that where once “one entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.”

After the destruction of Penn Station, Mayor Robert Wagner created the first Landmarks Preservation Commission. In 1965, the group helped pass the city’s first-ever landmark law so that something as drastic as the destruction of Penn Station never happened again. The landmark law passed unanimously.

But the landmark law didn’t have teeth. It didn’t protect anything inside a building or scenic parks. Most problematically, the commission didn’t meet very often—they gathered only six months per three-year period. When they were out of session, bulldozers and wrecking balls operated at will.

Courtesy of MTA/Flickr

Many historic buildings continued to fall even after the landmark law was passed. Among the victims were the Singer Building, once the tallest building in the world; the old Metropolitan Opera House; and Radio Row, an entire business district that was razed to make way for the World Trade Center.

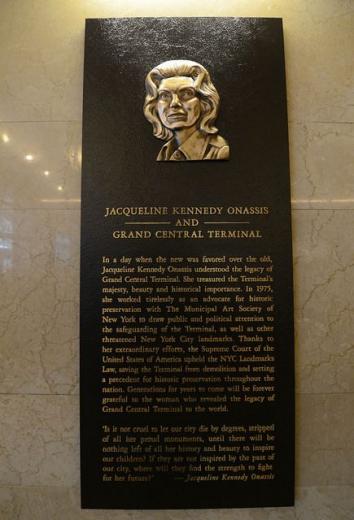

And in 1968, Penn Station’s old rival, Grand Central Terminal, was slated to join this list. But then it got a celebrity endorsement from Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

With Jackie O. so prominently involved, the fight went from a New York battle to a national one. The case went to the Supreme Court, and on June 26, 1978, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of New York City’s landmark law.

Justice William Brennan wrote of Grand Central’s architecture: “Such examples are not so plentiful in New York City that we can afford to lose any of the few we have. And we must preserve them in a meaningful way.”

For this story, reporter Ann Heppermann spoke with Jill Jonnes, author of Conquering Gotham; Peter Samton, a one-time architecture activist with AGBANY; reporter Roberta Gratz; and preservationist Kent Barwick. Editorial assistance was provided by Julia Barton.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.