Why Is Designing a Chair So Difficult?

Courtesy of jmv/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about chair design—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

“A chair is a very difficult object. A skyscraper is almost easier.” –Mies van der Rohe

Chances are that if architects—including Van der Rohe, Eames, Gehry, Hadid, Libeskind, Corbusier, and Breuer—have designed a big building, they’ve designed a thing on which to sit.

The chair presents an interesting design challenge because it is an object that disappears when in use. The person replaces the chair. So chairs need to look fantastic when empty and remain invisible (and ideally comfortable) while in use.

Again and again, new chair designs rise to this challenge, and more are coming out all the time. Some have argued that there are too many chair designs in this world, including one of the greatest headlines from the Onion: “Report Confirms No Need to Make New Chairs for the Time Being.”

Courtesy of Nelson Minar/Flickr

Yes, there are already a lot of chairs, but what we need from chairs are constantly changing. Consider the café: They used to be places for talking; now, they are places for working. People use the space differently, and the furniture must be adapted to serve the evolving use of a space.

Throughout our lives, we have been told to sit down. In school, in the office, in the polite company of a dinner party. In a car or a plane or a bus or a movie. We spend a lot of time in chairs. Which has led to a lot of talk lately about the unhealthiness of chairs. Sitting is the new smoking, says the Huffington Post, CBS News, Wired, Time, and the Mirror.

All of these new studies and scary headlines have created demand for new ways to sit. There are now medicine ball chairs, adjustable chairs, standing desks, treadmill desks, and even fetal position desks.

Courtesy of Alper Çuğun/Flickr

The chair backlash is upon us. Berkeley architecture professor Galen Cranz saw it coming.

In 1998, Cranz published The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body, and Design. The book's argument, essentially, is that we should stop sitting in chairs. Or at least for so long. Cranz says that three hours is the maximum time a body ought to spend sitting each day.

In her own life, Cranz takes innovative chair sitting to another level by attempting to “eliminate all conventional chairs.” Her house is full of floor cushions, tatami mats, and lots of hybrid chairs, such as a medicine ball on an office chair chassis, and one that looked like a sleek, pared-down horse saddle.

When she’s out in public and gets tired, Cranz opts to kneel, squat, lie down. “I lay down in a bank, and someone asked me if I was having a heart attack,” Cranz says. “I understand. But I said, ‘No, I’m fine, I’m resting because the line is so long!’ ”

It takes gusto to avoid chairs.

Courtesy of Weldon Kennedy/Flickr

Cranz explains that we all got suckered into the seated position once we got off the farm:

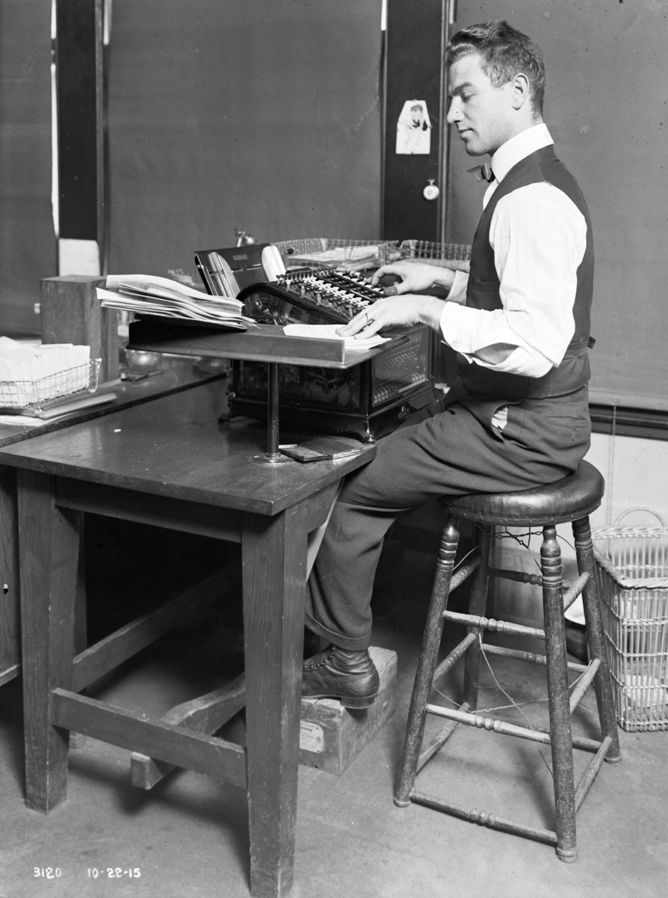

In the 20th century we moved from being an agricultural economy, where most people worked on farms, then we moved into a manufacturing economy, where a lot of people worked in factories. Some sat, some stood to work the machines along the conveyor belts, and then we moved into a service economy. And that seems to be where the chair really took off and became the dominant apparatus for our lives.

When we settled into the service economy, sitting became the position in which to type, file, and fill out paperwork. This is when office chairs became the chairs in which people spend most of their time.

Until very recent history, office chairs weren’t made to fit your body. They were made to fit your job. There were managerial chairs, middle-managerial chairs, secretarial chairs—the sizing was completely status-dependent. This meant that in some cases you could have a 120-pound executive sitting in a gigantic chair and a 160-pound assistant secretary sitting in a tiny chair. For the most part, status trumped ergonomics.

Then, in 1992, the Aeron chair was born. It came only in three sizes: small, medium, and large. The Aeron chair brought in an age of egalitarian office ergonomics, all made visible by the chair’s swivels and adjustment technology. All workers were equal in their Aeron chairs. And the Aeron chair defined what an office chair ought to look like.

Courtesy of Cubicle Sherpa/Flickr

Though expensive, the chairs saw extraordinary demand. Perhaps, in part, because of a growing number of repetitive strain injury lawsuits. Companies suddenly found it cheaper to buy fancy adjustable chairs than to pay for legal settlements or medical bills.

But fixing the chair doesn’t totally solve the problem. It turns out that the chair has an accomplice: the desk.

Flat surfaces force you to bend forward. Even if you have excellent posture, you still tend to lean over your keyboard, or your dinner, or your book. The spine curves into a big C-shape, which is awful for your spine, and also compresses your organs and limits their functions.

Because of this chair/desk paradigm, the ability of chair backs to really solve this problem is limited.

If you must sit in a chair, Cranz says it’s best to ignore the chair back and sit yourself right at the edge of your seat, essentially turning the chair into a stool. Stools, says Cranz, are a good alternative to chairs, because they get your body out of the C-shape. They position the body halfway between sitting and standing.

Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives/Flickr

Still, it’s not like there should be one single piece of furniture to correct all the problems of chair-sitting.

“The lounge chair is not the answer. There’s no the answer. What we need is variety,” according to Cranz. “The best posture is the next posture.”

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.