Was the 1977 New York City Blackout a Catalyst for Hip-Hop’s Growth?

Photo by Dan Farrell/NY Daily News via Getty Images

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about the NewYork City blackout that may have catalyzed the hip-hop movement—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

On July 13, 1977, lightning struck an electricity transmission line in New York City, causing the line’s automatic circuit breaker to kick in. The electricity from the affected line was diverted to another line. This was fairly normal, and everything was fine—until a second bolt of lightning struck.

Electric lines started turning themselves off. As more and more lines failed, the whole system faltered. Eventually, the largest power generator in the area, known as Big Allis, shut down.

Courtesy of Harald Kliems/Wikimedia Commons

And then all of New York City went dark.

On that evening, DJ Grandmaster Caz, a Bronx native, and his DJ partner, Disco Wiz, were spinning records in a park. They had their sound system plugged into a lamppost. Caz recalls the evening: “The record just started slowing down, you know what I mean? So, quite naturally, we thought, it was us. We thought we had drained too much power and we shorted out the electricity. So we’re frantic, we’re looking around, we’re checking buttons, were checking switches, we’re seeing what’s up.”

But Caz and Wiz hadn’t shorted out the electricity. New York was in the middle of a citywide blackout—with power failing in all five boroughs—and pretty soon, things started to get tense. As Caz recalls, “The stores started to close. Like the local bodegas on each corner—we would hear the gates slamming down. It was like they knew what was happening, they knew what was going on, they was like, ‘We closing up now.’ ”

Courtesy of Delaney Hall

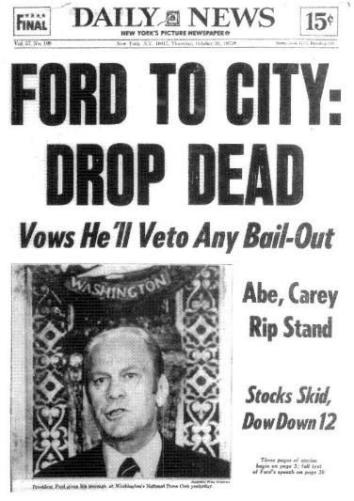

In 1977, New York City was in dire financial straits. A couple of years prior, in 1975, the city had turned to the federal government for a bailout. President Gerald Ford’s response was a resounding no, prompting the New York Daily News to run the now famous headline: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

Ford never actually told New York to “drop dead,” but that’s how a lot of New Yorkers felt. And in the Bronx, people felt even more abandoned. Public programs had been cut, arson was rampant, and poverty was rife. The neighborhood was full of abandoned and burned-down buildings.

Joe Schloss, who researches hip-hop culture at City University of New York, said of the city in 1977: “It was like a powder keg. All it took was something to push it over the edge.”

New York had experienced blackouts before—there was a major outage in 1965 during which New Yorkers stayed mostly calm—but in 1977 the city experienced widespread looting.

“It was chaos that night,” says Caz. “And it was exciting afterwards. But while it was going on, it was scary.”

But Caz also believes that the 1977 blackout may have accelerated the growing hip-hop movement, which was just beginning to put down roots in the Bronx. His theory: The looting that occurred during the blackout enabled people who couldn’t afford turntables and mixers to become DJs.

Caz admits that he himself stole new equipment that night. “I went right to the place where I bought my first set of DJ equipment, and I went and got me a mixer out of there.” He continues, “After the blackout, all this new wealth … was found by people and they just—opportunity sprang from that. And you could see the differences before the blackout and after.”

Caz’s theory—that the hip-hop movement was catalyzed by the 1977 blackout—can’t really be confirmed. Joe Schloss, the hip-hop researcher from City University, buys it, with a caveat. “I think it’s true, but I think it’s also important to keep in mind that basically, hip-hop history is an oral history at this point, and that it’s all mythology in some sense—the true stories as well as the false stories.”

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.