How Landlocked Dallas Once Tried to Become a Port City

Courtesy of Richard Cahan

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about the port of Dallas—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

The above photo taken in 1899 of three fashionable men suspended midair on the lifted arm of a giant dredging machine is a scene from the reversal of the Chicago River.

There are plenty of images like this from this era—scenes of people standing around proudly as they shaped the earth. And in these old photos there seems to be a real sense of awe and reverence for the marvels of civil engineering.

The reason that photo is famous—or at least famous enough for us to have seen it—is because the reversal of the Chicago River was an enormous engineering project that was successful.

But you have to figure that there were countless other photographs depicting similarly awe-inspiring feats of engineering prowess that we have never seen—because those feats turned out to be failures.

Consider the scene below from another feat of civil engineering: the creation—or the attempted creation—of the port of Dallas.

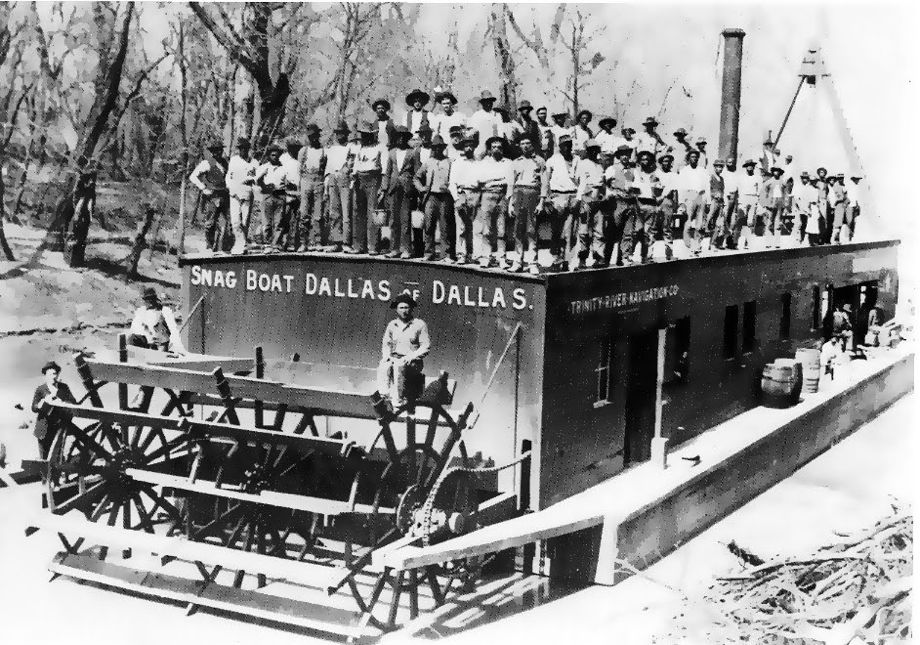

Courtesy of Dallas Public Library Archives

In 1892, the good ship Snag Boat Dallas of Dallas was employed to clear debris (called “snags”) out of the Trinity River in order to make the river navigable to ships. Dallas, it was imagined, could be a port city to the Gulf of Mexico.

Dallas, though, is about 300 miles to the Gulf as the crow files. With all the Trinity River’s twists and turns, it’s actually more like 700 miles of river.

Courtesy of Google Maps

Still, the Snag Boat Dallas of Dallas was able to clear the river well enough to allow the passage of another well-named boat, the steamship H.A. Harvey Jr.

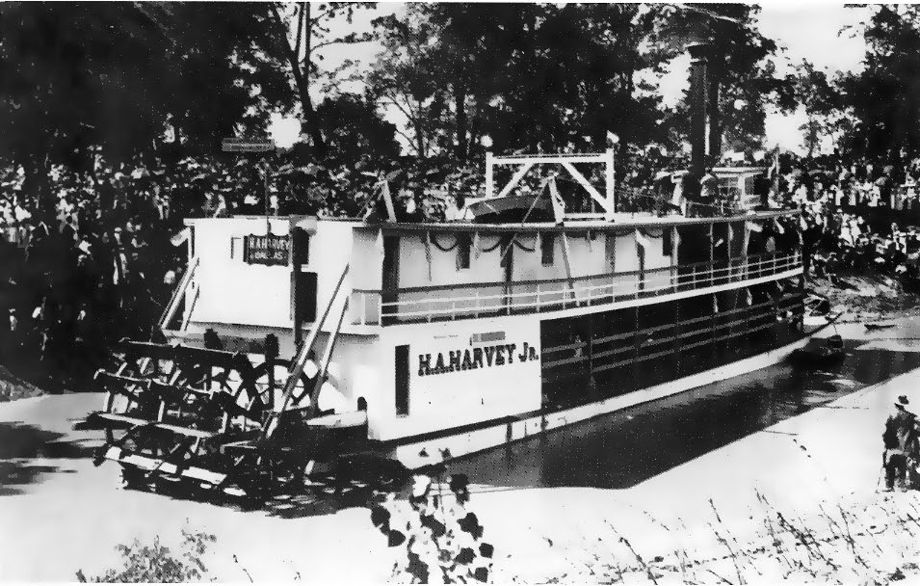

Courtesy of Dallas Public Library Archives

When the H.A. Harvey Jr. arrived in Dallas in 1893 from the Gulf of Mexico, the city went berserk. The front page of the newspaper was printed in red ink because they were ecstatic to be becoming a port city. But the Trinity River still was not easily navigable.

Dallas persuaded Congress to survey the river and figure out where locks and dams could help make it navigable. The Army Corps of Engineers finished the first lock and dam in the early 1900s at a site 13 miles below Dallas. But eventually Congress shelved the project. The locks and dams that had already been built moldered.

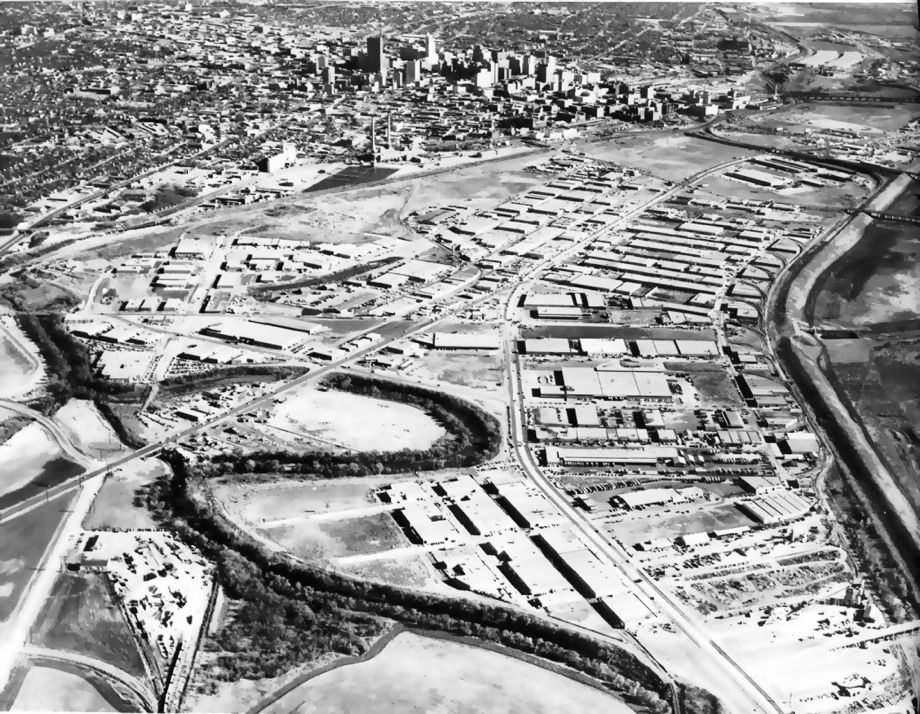

Then, in 1908, the Trinity River flooded and made a mess of Dallas. As a result, Dallas hired esteemed urban planner and landscape architect George Kessler. The so-called Kessler Plan would transform the Trinity River into a straight channel about a half-mile west of its existing course through Dallas. Levees would contain the new channel and open up miles of floodplain for development right next to downtown. Not all of the Kessler Plan came to pass, but the river was diverted and channeled into a 26-mile canal, as seen below:

Courtesy ofIndustrial Properties Corporation: Our 60 Years, 1928-1988.

In a series of fits and starts over the next 55 years, the port of Dallas project kept moving forward. In anticipation of the imminent navigability of the Trinity River, new freeway bridges constructed over the river were built extra tall to allow seagoing vessels clearance underneath. But by the time the money and political clout was ready to finish the project once and for all, Dallas didn’t really need a seaport. The new DFW Airport would do just fine.

So the city of Dallas moved their river from the center of town to a walled-off floodplain for a port of Dallas that never came to pass, and for years the diverted river festered. It became a place to dump sewage, trash, and even bodies. No one went there on purpose.

But now, things are finally starting to change. The Trinity River is becoming a public green space. Making the diverted river easily accessible for public use is a huge urban-planning challenge for Dallas. But little by little, people are starting to use the river. There are some trails for bikes and walking, and you can even take a kayak trip.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.

Correction, Sept. 25, 2014: This post originally included a photo of Dallas’ Margaret Hunt Hill and Continental Avenue bridges and stated in the caption that they were built to be tall enough to allow ships to pass underneath. They were not. This photo has been removed.