How to Design the Perfect Bank Heist

Courtesy of Ilona Gaynor

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at the Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about bank heists—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

In 2011, architect Armin Blasbichler asked his architecture students at the University of Innsbruck to plan bank heists because, as he says, “architects have a specific view on buildings and organizational structures—on how things relate together, weak points and strong points.”

Blasbichler certainly wasn’t the first to think of a heist as architectural or artistic practice. As far as we know, Janice Kerbel was the first artist to do it—she meticulously planned out her heist on a London Bank and detailed it in an exhibition and book.

But authors and screenwriters did it long before she did (though maybe not as meticulously). This week, we look at three different heists—dreamed up by an artist/designer, a writer, and an actual bank robber—with designs that range from the spectacularly complicated to the deceptively simple.

Courtesy of Ilona Gaynor

Heist No. 1: Under Black Carpets. Mastermind: Ilona Gaynor. Location: Los Angeles.

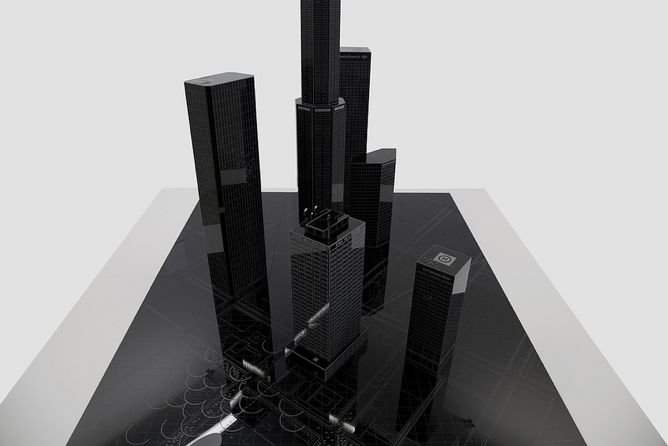

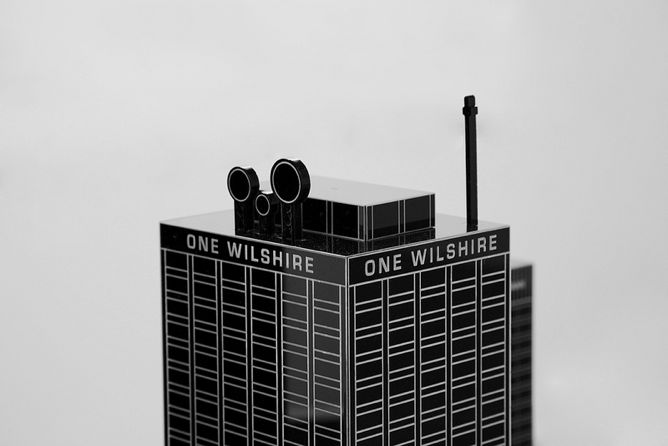

Ilona Gaynor is a designer and artist based in London whose work is influenced by Janice Kerbel. One of Gaynor's ongoing projects is a design proposal for an art exhibition that would recount the story of an intricate fictional heist using model constructions like those seen here, short films, sculptures, and photographic prints.

Her imaginary heist is set in Los Angeles, because she’s interested in the “feedback loop” that happens between real-life heists and those in Hollywood movies. From about 1960 to 2000, L.A. was the bank robbery capital of the world. In the worst years there were more than 2,500 robberies a year in L.A.; that’s about one robbery every 45 minutes of the working day. In 1983, L.A. had more robberies than the next four cities (New York; San Francisco; Portland, Oregon; and Sacramento, California) combined.

Courtesy of Ilona Gaynor

L.A.’s bank robbery statistics are now much less jaw-dropping; in 2013 there were only 212 reported robberies. Some have conjectured that the physical layout of L.A. played a role in making it the bank robbery capital of the world for several decades. Gaynor thinks it may have had something to do with the “intrinsic pull of Hollywood on everything having to do with the iconography of a heist.”

In the spirit of the Hollywood-style heist, Gaynor’s heist, which is meant to be a spectacle, begins with a plane crashing into the high-rise, One Wilshire (a building that houses computer servers) in L.A. As emergency responders are busy with this distraction, five banks in the immediate surrounding area are being robbed. Gaynor’s plan involves drilling concentric circles into the banks, pulling out the vaults, and loading them onto a truck.

Heist No. 2: Inside Man. Mastermind: Russell Gewirtz. Location: New York City.

In the early 2000s, Russell Gewirtz—who is best known for writing the screenplay for Spike Lee's Inside Man—wasn’t a writer, hadn’t been to film school and had nothing to do with Hollywood. He was just a guy, working in real estate, who liked thinking about the “perfect heist” as he walked past an empty bank on his way to work every day. Those daily musings eventually turned into the plot of Inside Man.

Gewirtz decided that the perfect heist could be done by dressing the hostages up like the robbers so that when it was all over, the police wouldn’t be able to tell who was who.

The hostage/robber switcharoo was clever, but Gewirtz knew he still needed a way for the robbers to get their stolen goods out of the bank. The stolen goods couldn’t go out with the hostages/robbers, so he decided to have the robbers literally build a solution. They construct a small cell with a false wall hidden behind some shelves in the basement of the bank. One of the robbers stays hidden in this cell for a full week until the police are done gathering evidence.

Heist No. 3: Choir Boy Robber. Mastermind: Tom Justice. Locations: Illinois, California, Wisconsin.

The imaginary heists designed by Gaynor and Gewirtz are both extremely complicated and involve multiple players and a lot of moving parts. In other words, their designs leave open a lot of chance for things to go wrong.

Sometimes simple is best. Just take it from Tom Justice, a real-life bank robber who stole close to 130,000 dollars from 26 banks in Illinois, California, and Wisconsin over the course of four years.

Tom Justice would go to a bank alone, approach a teller, present a note saying this is a robbery, and walk out without a lot of fanfare—which, according to FBI statistics, is how most bank robberies happen. And unlike the previous two designers, Justice actually carried his out in real life.

The FBI called Justice the “Choir Boy Robber” because he always folded his hands and set them on the counter and kept his head slightly bowed.

Before his first few bank robberies, Justice practiced obsessively. His bicycle was his get-away vehicle, and so the first thing he’d do was figure out where he was going to leave the bike (unlocked) while he was inside robbing the bank. From there, he counted steps, observed police patterns and made notes for months before actually carrying through with the robbery.

In his last few robberies, Justice did less planning and stopped observing local police patterns. While leaving the scene of his last robbery, he was questioned by a police officer and had to ditch his custom-made racing bike and abscond on foot. They didn’t find Justice, but they found the bike, which they ultimately traced back to him. Tom Justice spent nine years in prison and was released in 2010.

Everyone we interviewed for this story named Michael Mann's 1995 film Heat as their favorite heist movie. Justice said, “in prison, Heat is the No. 1 movie amongst convicts.”

In 1997 there was an actual robbery at a Bank of America that unfolded in a manner that seemed to some people (including artist Ilona Gaynor) to be suspiciously similar to the events in Heat. As in the movie, the heist ended in the “North Hollywood Shoot-Out,” a violent exchange of gunfire between the robbers and police.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.