Was This Woman a Heroine or a Villain?

Courtesy of Craig Michaud via Wikimedia Commons

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at the Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about controversial monuments to Hannah Duston—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

About 10 miles north of Concord, New Hampshire, off of Interstate 93, there’s a little island with a great, big monument on it.

A close-up view reveals that the monument depicts a woman holding a hatchet in her right hand and a bunch of scalps in her left:

Courtesy of Marc Nozell via Flickr

When it was erected in 1874, this was the first statue to honor a woman in the United States. But despite this historic status, the monument is controversial because of the woman it memorializes and what she did.

The woman in the monument is Hannah Duston (sometimes spelled Dustin) and in 1697 she was living in Haverhill, Massachusetts, when she, her infant daughter, and her nurse-maid, Mary Neff, were kidnapped by a band of Abenaki Native Americans. The three were marched north and at some point Hannah’s infant daughter was killed by the Abenakis. They stopped for the night in Boscawen, New Hampshire, (on the island above, where the monument now stands) and while the Abenaki families slept, Hannah and her companions killed 10 of them—including six children—and then scalped each victim before making their escape back to Haverhill.

Illustration by Junius Brutus Stearns (1810–1885) via Wikimedia Commons

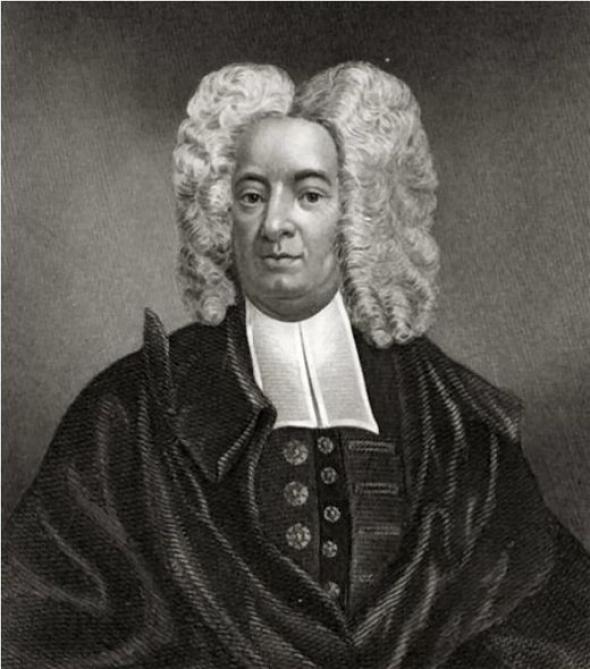

After she returned home, Duston and her husband traveled to Boston where she told her story to a Puritan minister named Cotton Mather. Mather wrote it down and told it to rapt church-goers throughout the colonies.

Illustration by Peter Pelham via Wikimedia Commons

Hannah Duston’s story was revived again in the 1800s during the era of “Manifest Destiny” by writers such as Henry David Thoreau and John Greenleaf Whittier, who were looking to tell the stories of American heroes and heroines. But as the original Cotton Mather version of the story was rewritten and retold, people changed the narrative to suit their purposes—often omitting the part of the story in which Duston and her companions kill the sleeping children.

In 1879 another monument was erected in Haverhill, Massachusetts, showing a more fierce Hannah Duston. This monument also features bronze illustrations of other parts of Duston’s story:

In addition to the monuments, there are landmarks in her name—memorial boulders, streets, a nursing home. There are kitschy items like this Hannah Duston whiskey decanter, commissioned by Jim Beam in the 1970s, as well as a Hannah Duston bobble-head, which you can still purchase at the New Hampshire Historical Society museum store. These items are offensive to some people who know the whole story, as are the monuments in Boscawen and Haverhill. The monument in Boscawen is often covered in graffiti; Duston’s nose has been shot off with a rifle. Every few years someone proposes to tear it down, or clean it up, or amend the signage to tell more of the history. With every proposal comes a public argument. Is she a heroine, or is she a villain?

The debate continues, but for now, the monument on the island remains neglected and crumbling. It’s fitting, too, as that’s probably the most accurate symbol of how people feel about Hannah Duston today—ambivalent about who she was, but not quite ready to let her go.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.