The Allure of Unbuilt Structures

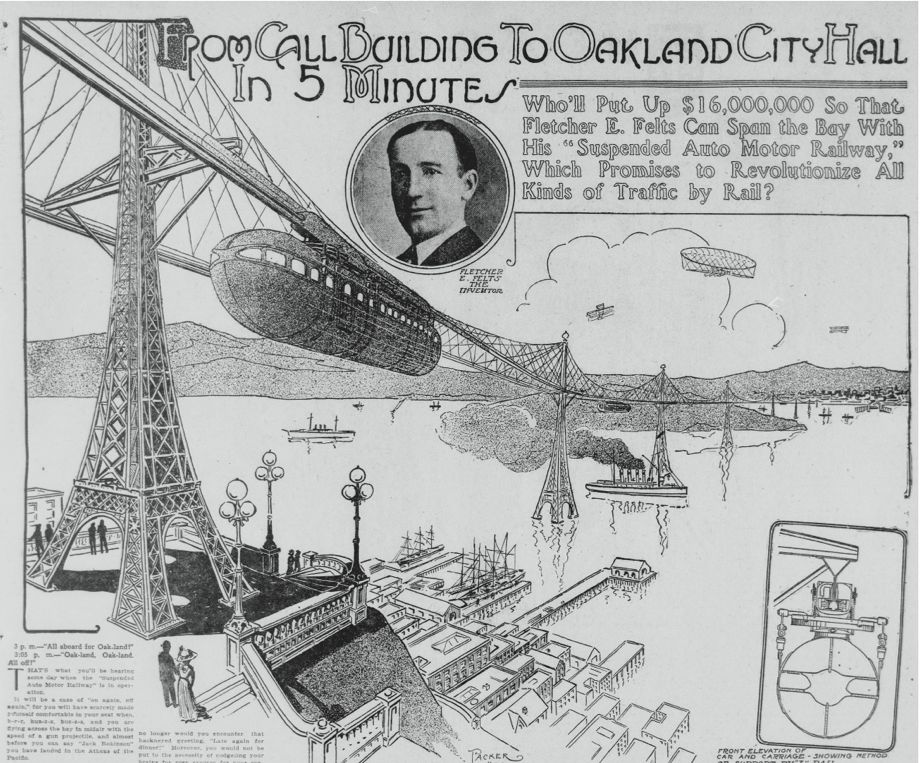

Image courtesy The Urbanist via the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibiliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside.

By far the best design podcast around—and one of the best podcasts, period—is Roman Mars’ 99% Invisible. On it he covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at the Eye, we will be cross-posting his new episodes so you can check them out, and we’ll also host excerpts from his podcast’s terrific blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

Starting in February 2014, he plans to take season 4 of the show weekly; you can support his Kickstarter campaign here.

His most recent show—about the allure of the unbuilt—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

There is an allure to unbuilt structures: the utopian, futuristic transports; the impossibly tall skyscrapers; even the horrible highways. They all capture our imagination with what could have been.

Imagine Fletcher E. Felts’s “Suspended Auto Motor Railway,” a high-speed funicular suspended from a bridge of soaring towers over the Bay, connecting downtown San Francisco to Oakland, as seen in the illustration above. An article in the San Francisco Call published on April 17, 1910 describes it this way:

"It will be a case of ‘on again, off again’ for you will have scarcely made yourself comfortable in your seat when b-r-r, buz-z-z, bu-z-z-z, and you are flying across the bay in midair with the speed of a gun projectile, and almost before you can say “Jack Robinson” you have landed in the Athens of the Pacific.

Now that’s rather a startling statement, isn’t it? But Fletcher E. Felts who has looked into the future, says we are going to have such a railway.

“Oh, pshaw!” you say contemptuously, “It’s only a dream.” But, you know, some dreams come true.”

Felts’s unbuilt auto motor railway reminds us of when we used to dream big.

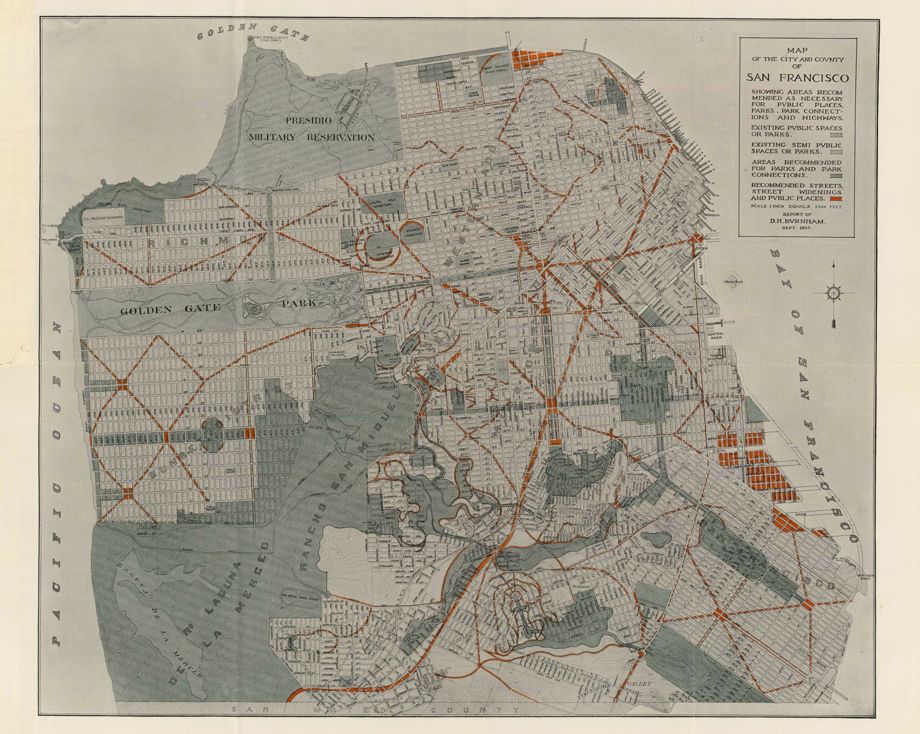

So, too, does Daniel Burnham’s vision of a San Francisco "City Beautiful." Daniel Burnham was the mastermind behind the White City at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was the pinnacle of the "City Beautiful” movement, which espoused big civic centers and grand neo-classical structures to stir the soul.

Burnham was hired by big-time downtown business owners of San Francisco to turn this raggedy (if well-off) city into something majestic. Burnham’s team showed up and they set up shop in a cottage on the summit of Twin Peaks so they could survey the city and craft the perfect plan…which was completed in the fall of 1905.

Image courtesy The Urbanist via the David Rumsey map collection

And the legend goes, all the books were delivered to city hall for distribution on April 17, 1906—the day before the great earthquake pulverized San Francisco.

When you’re tasked with starting something over from scratch, you can use that as an opportunity to create an ideal version of what you’re rebuilding, or you can do it fast and cheap and the closest to what you remember it being like before. Tragically, San Francisco authorities went with the latter.

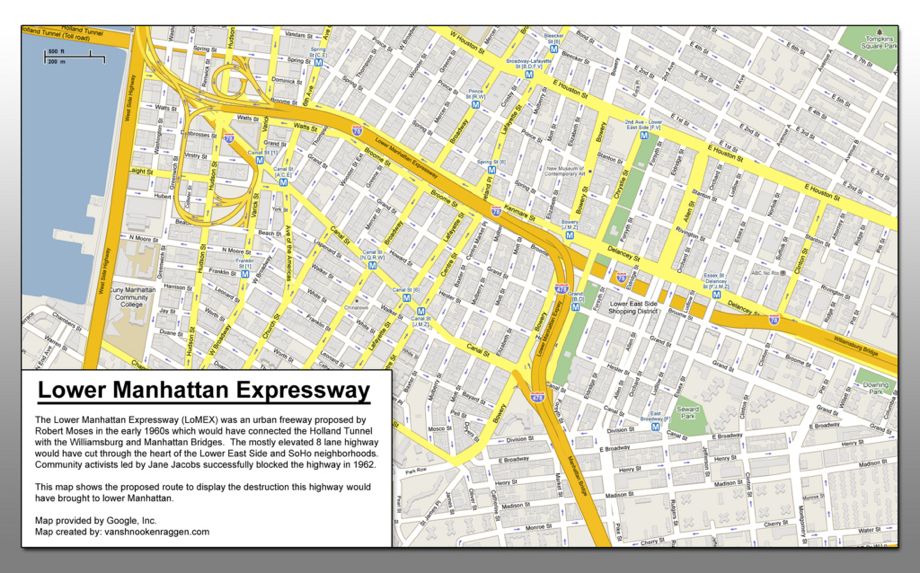

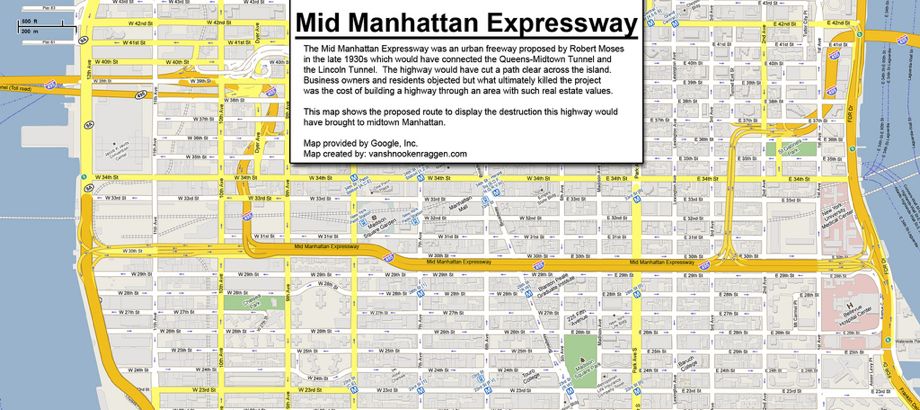

Yet as much as we curse our forebears for their shortsightedness for not realizing Burnham’s imperial city or the gunshot funicular, we are actually a richer society in the absence of most of what never got built. And, of course the unbuilt world spans coast to coast. Case in point: mid-20th-century Lower Manhattan (as imagined below).

Image courtesy Andrew Lynch

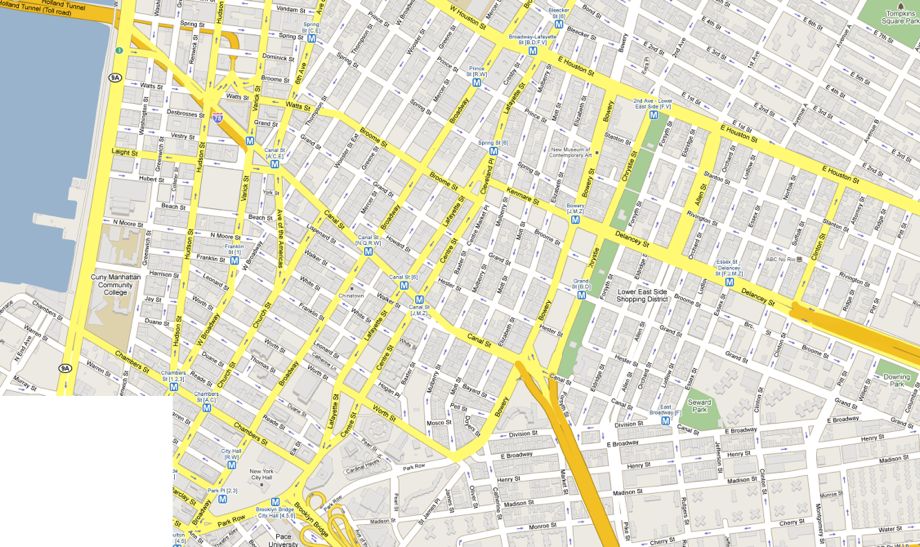

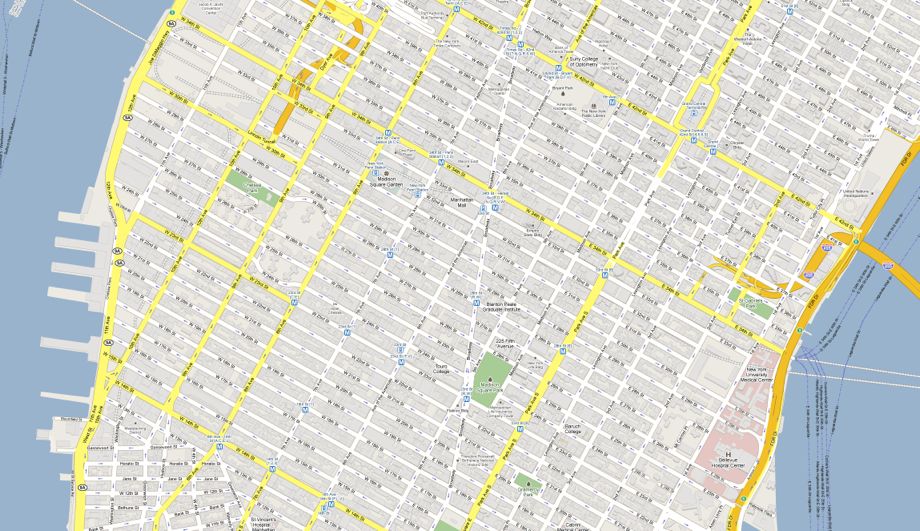

Manhattan today actually looks like this:

Image courtesy Google Maps

Here's another one that came very close to becoming a reality:

Image courtesy Andrew Lynch

And here's what really is:

Image courtesy Google Maps

These fake maps were created by an artist/cartographer/realtor in New York City named Andrew Lynch, who goes under the name Vanshnookenraggen. Andrew wanted to see what what New York City would look like if Robert Moses had succeeded in building two giant expressways through the densest place in the United States.

For the unacquainted, Robert Moses was the man behind these plans, and the true power broker of New York. In fact, Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1100-page opus about Moses is called The Power Broker.

Moses built bridges, and beaches, and highways, and public housing, and he did a lot of the master planning of New York City and surroundings. He even restructured the city governance. But some of what he’s most famous—or really, infamous—for is what didn’t get built. These proposed highways would have completely altered the urban fabric of New York City. Whole blocks would have been leveled. On and off ramps would wind around buildings, and make the experience of walking around Manhattan completely terrible.

The highways were controversial in terms of how much they would have disrupted the city. Jane Jacobs, an activist, urbanist, and resident of Greenwich Village, fought Moses’ plan, and in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she went on to describe the interrelatedness of the urban fabric with civic life. She called it “the intricate sidewalk ballet.”

In a strange way, Moses’ Lower Manhattan Expressway helped crystallize the story of Jacobs' neighborhood. It’s almost as if the threat from this unbuilt road made Greenwich Village into the place it now seems destined to have become.

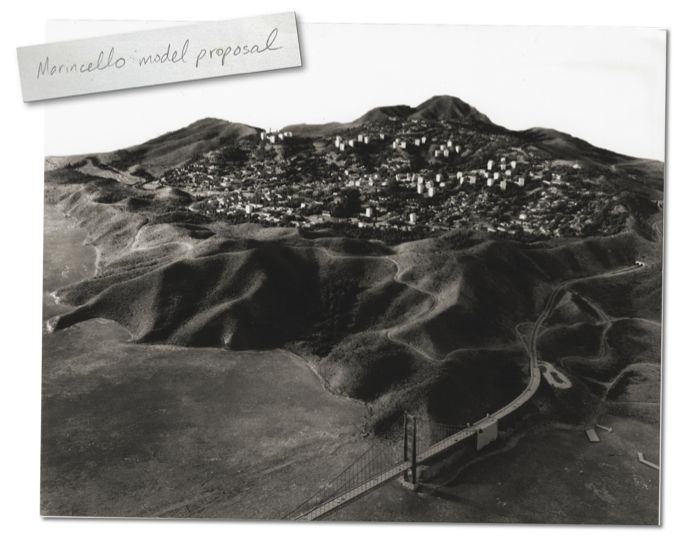

Which brings us back to the the Bay Area. The Marin Headlands is a landscape of beautiful rolling hills on the north side of the Golden Gate Bridge, opposite San Francisco. It’s striking because of what isn’t there. It is a pristine recreational area a stone’s throw away from one of the most expensive cities in the world. It’s hard to believe no one tried to build on it. But, of course, someone did.

Image courtesy Aaron Ximm

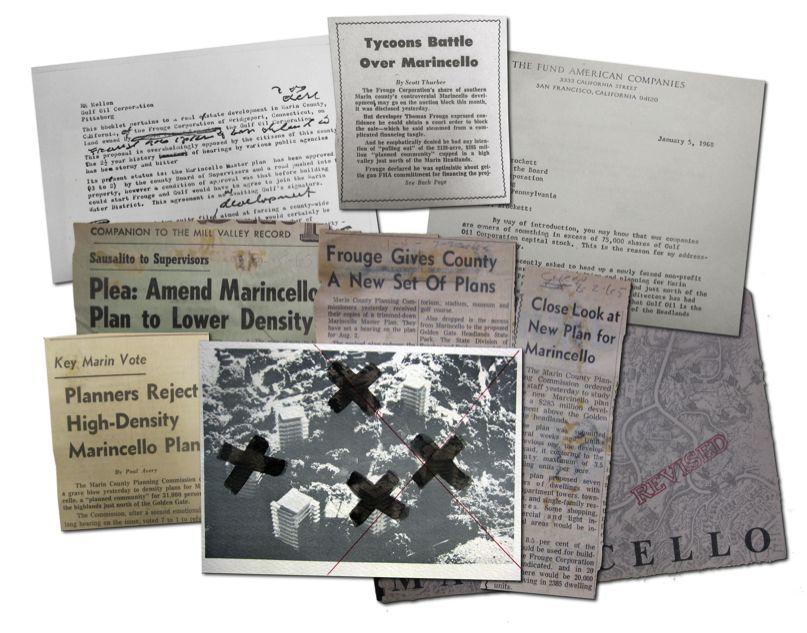

Marincello was a massive proposed development of houses and towers that sailed through committee without too much controversy. But once the public caught wind of the plan, a group to block it sprung into action. The threat from Marincello spurred the creation of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area that protects the Headlands from all future development.

Image ourtesy Aaron Ximm

Marincello may be unbuilt, but to say that there’s nothing there in the Headlands is not seeing the grand thing San Francisco actually did build for itself and everyone who visits. What they actually built was a magnificent wilderness. They built the very reason we all love it.

To learn more about unbuilt structures and to see additional photos, read the rest of the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show. 99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.