How to Build a Housing Bubble

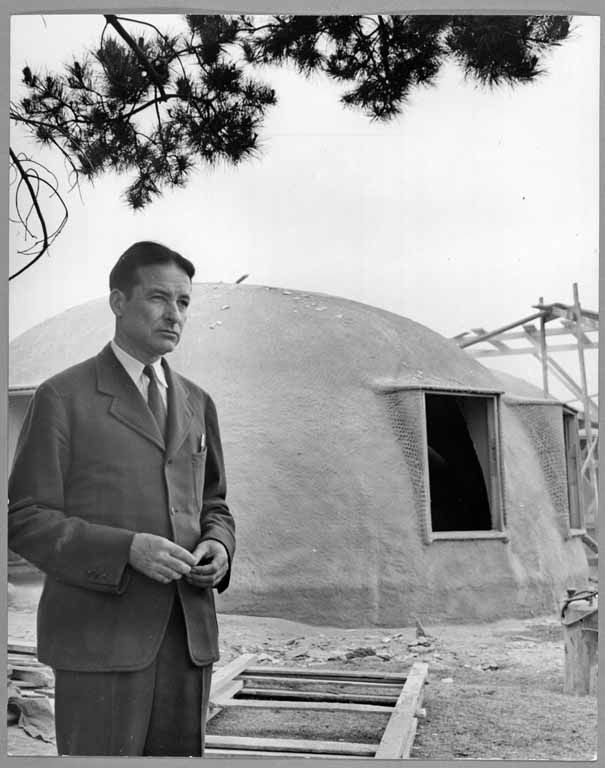

Wallace Neff, Courtesy of Jeffrey Head

By far the best design podcast around—and one of the best podcasts, period—is Roman Mars’ 99% Invisible. On it he covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at the Eye, we will be cross-posting his new episodes so you can check them out, and we’ll also host excerpts from his podcast’s terrific blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

His most recent show—about bubble houses—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

If you were a movie star in the market for a mansion in 1930s Los Angeles, there was a good chance you might call on Wallace Neff.

Neff wasn’t just an architect–he was a starchitect. One of his most famous projects was the renovation of Pickfair, the estate owned by the iconic silent film actress Mary Pickford, and her husband Douglas Fairbanks. If you were lucky enough to be invited to dinner at Pickfair you might find yourself seated next to Babe Ruth, the King of Spain, or Albert Einstein. Life magazine called Pickfair “only slightly less important than the White House, and much more fun.” Neff designed estates for Charlie Chaplin, Judy Garland and Groucho Marx, and his Libby Ranch is now owned by Reese Witherspoon.

But it was the 1,000-square-foot concrete bubble house where Neff lived out his final days that he considered one of his greatest architectural achievements.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Near the end of World War II, architects were anticipating the post-war housing shortage. Neff wanted to create a solution that would not only meet this demand, but address the need for housing worldwide.

The idea came to Neff one morning when he was shaving. He looked down and noticed a soap bubble that had formed on the sink. He reached out and touched it. The bubble held firm against his fingertip. That was the moment the idea struck him. He could build with air. He could make a bubble house.

Having already made his fortune as an architect for the rich and famous, Neff wasn’t in it for the money. He wanted to engineer an innovative way to provide low-cost housing.

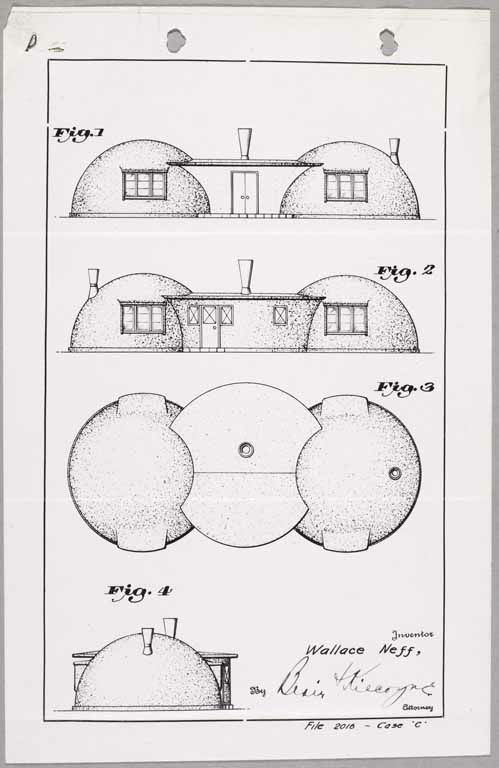

Dome-shaped living structures were not a new idea. The indigenous Acjachemon of Southern California had wickiups, the Ojibwe had wigwams, and the Inuit had (and still have) igloos. During Neff’s lifetime, Buckminster Fuller was creating his own circular solution to the housing shortage: The Geodesic Dome. (See 99% Invisible Episode #64). But Neff’s so-called Airform design was unique.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

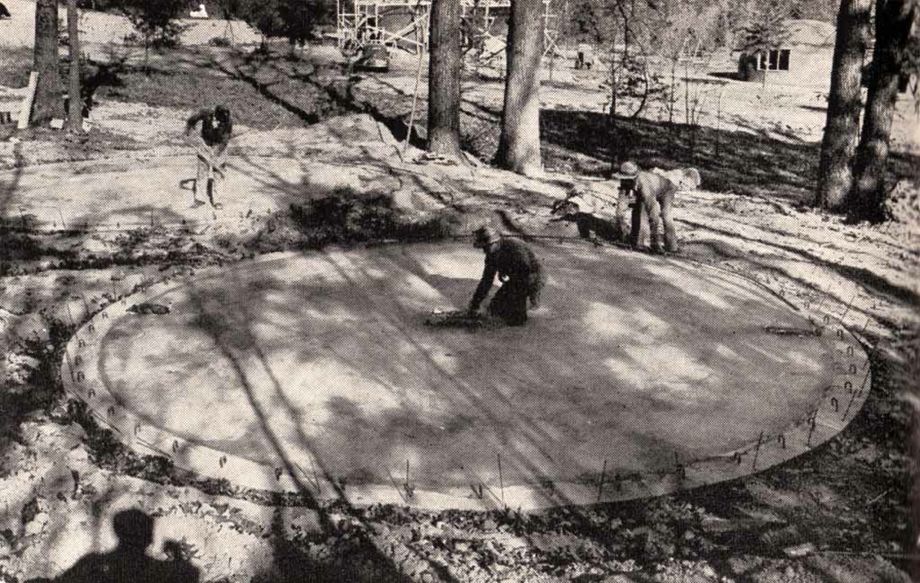

First, a big slab of concrete was poured in the shape of a giant coin.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Next, a giant balloon was inflated and tied down to the foundation using steel hooks.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

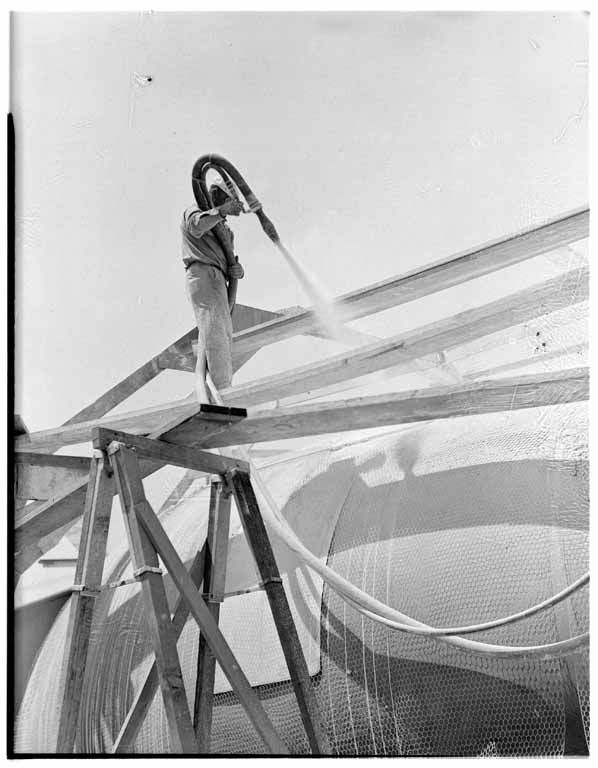

The inflated balloon was coated in a fine powder, then covered with gunite, the product of water and dry cement mix combined at high pressure and shot out of a gun.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Two men with a balloon and a gunite machine could turn a bare patch of soil into a bubble house in less than 48 hours. After the gunite dried the balloon was deflated and pulled out through the front door so it could be used again on the next house.

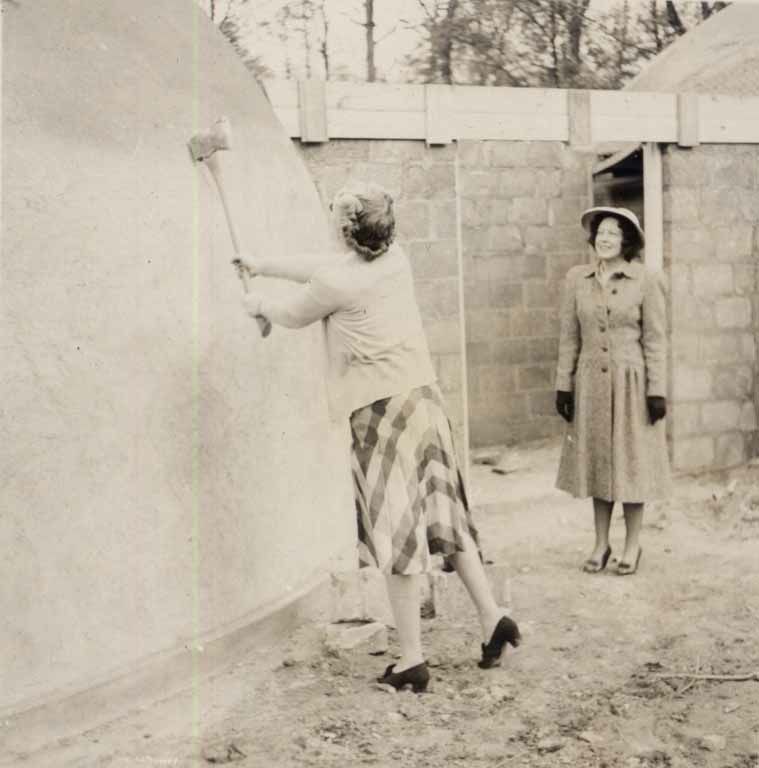

Dried gunite was more than twice as strong as regular concrete. Neff was so confident in his design that he would invite people to bash the walls of the bubble with the back side of an axe. The axe would just bounce off.

Courtesy of Steve Roden and Jeffrey Head

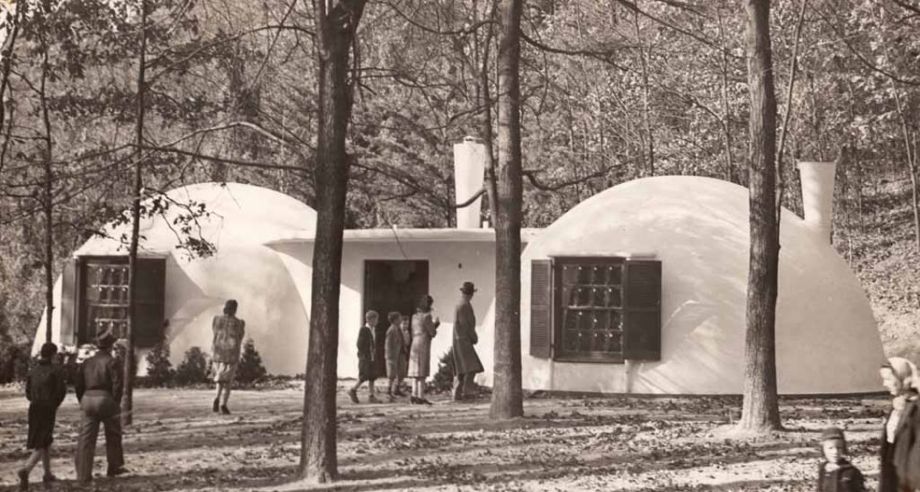

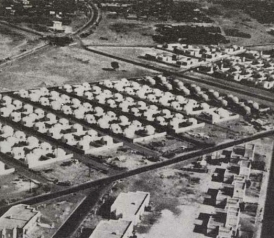

In October of 1941, Neff began construction on a community of 12 bubble houses in Falls Church, Virginia. Paid for by the federal government, it housed government workers. The neighborhood would eventually take on the nickname Igloo Village.

Life in a bubble house could be problematic. Round rooms were challenging to furnish, and the concave walls were not conducive to hanging pictures.

Huntington Library, Maynard Parker Collection

Igloo Village was isolated in the middle of the damp woods, and mold would creep inside the house. Kids from neighboring towns liked to drive by to ogle the bubble houses at night, disturbing the peace with their glaring headlights.

Nevertheless, Neff was able to land a few more clients. The Southwest Cotton Company hired him to build a desert colony of bubble houses in Litchfield Park, Arizona. Loyola University in Los Angeles ordered a bubble house dormitory. And in 1944, the Pacific Linen Supply Company commissioned a bubble structure 100 feet in diameter and 32 feet high–the largest ever built.

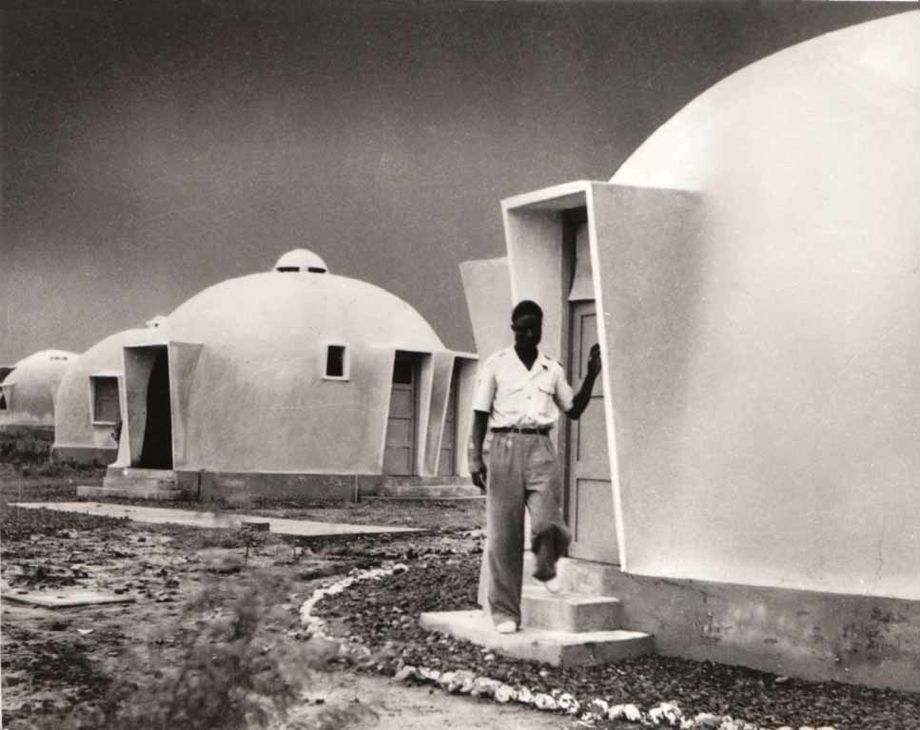

Neff’s bubble eventually burst, as all bubbles do. With the exception of a structure in Pasadena that Neff himself lived in, every one of Neff’s bubble houses in the United States have been demolished. But his idea spread to Pakistan, Egypt, Liberia, India, Jordan, Turkey, Kuwait, South Africa, The Virgin Islands, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Cuba, Brazil and Dakar, where many of the 1200 bubbles houses built in the 1950s–the biggest collection anywhere–are still around today.

Wallace Neff, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Candice Felt, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Special thanks to historian Jeffrey Head, author of No Nails, No Lumber: The Bubble Houses of Wallace Neff.

To learn more about Neff’s bubble houses, read the rest of the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show. 99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.