With a potentially strong hurricane bearing down on the United States the same week as Hurricane Katrina’s 10-year anniversary, it feels like a good time to take a step back and think about what’s different now.

As far as meteorology is concerned, Katrina may as well have been a century ago.

After the disastrous 2005 hurricane season, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began to plan for a crash course in greatly boosting the accuracy of hurricane forecasts. The Bush administration approved the Hurricane Forecast Improvement Project in 2008, and it has since exceeded even its own lofty goals.

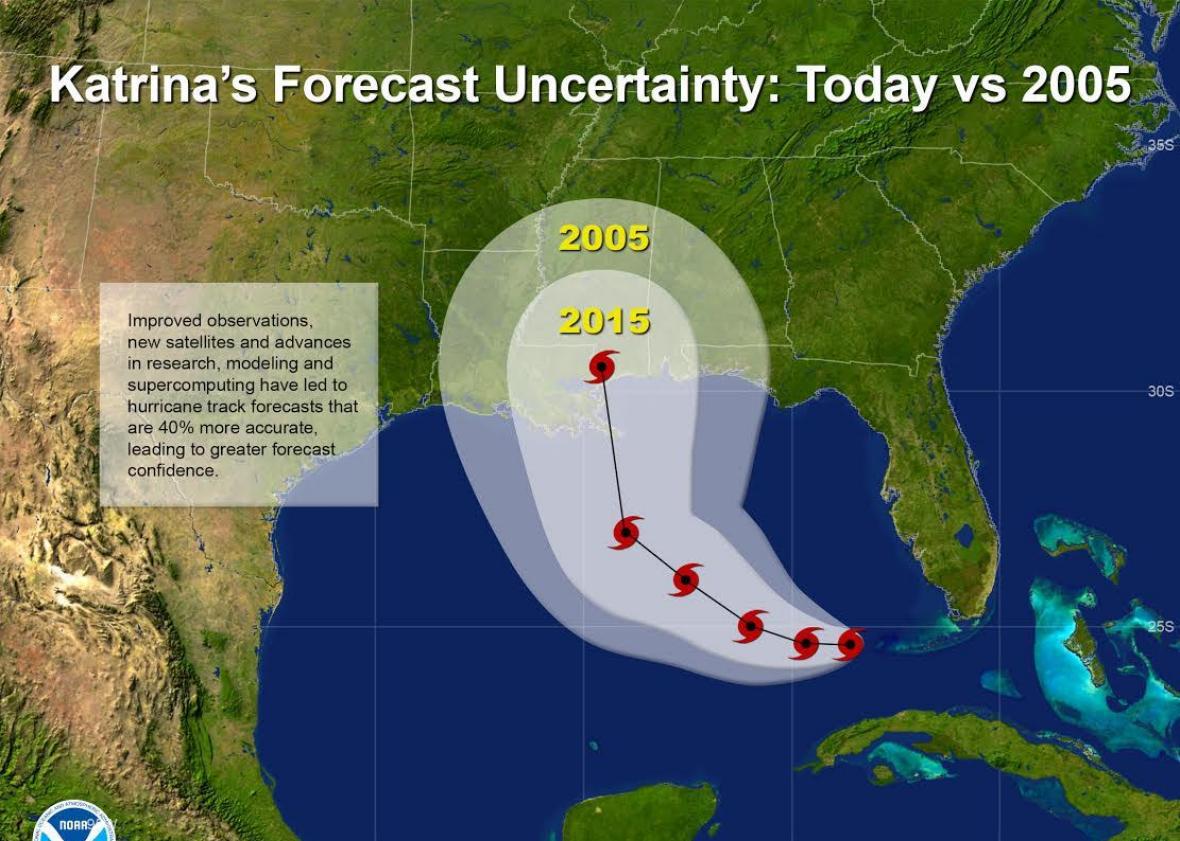

In a statement Wednesday, NOAA said: “Since the 2005 hurricane season, NOAA has launched 5 new satellites, deployed new coastal observing systems and made major breakthroughs in oceanic and atmospheric research, all of which has resulted in a remarkable *40% reduction* in the margin of error of a hurricane’s expected track.”

Seen graphically, the result is stunning:

In a tweet earlier this year, Eric Blake, a hurricane specialist at the National Hurricane Center, called the stunning improvement in hurricane track forecast accuracy over the last decade “one of the most incredible success stories of our lifetimes.” Five-day forecasts today are just as accurate, on average, as three-day forecasts were the year of Katrina. That means two extra days for people in the path to prepare.

Forecasting hurricane strength days in advance has historically proven more challenging than track forecasting, but there’s been vast recent improvement there, too. The U.S. flagship high-resolution hurricane model, the Hurricane Weather Research and Forecasting Model, has improved its accuracy at a rate of 10 to 15 percent per year since 2011.

Earlier this year, HFIP fell victim to its own stunning success, and the budget took a big cut. But the program should still be able to benefit from a massive new NOAA investment in faster supercomputers.

You’d be forgiven if you haven’t noticed much benefit from the vastly improved hurricane forecasts. That’s mostly because, with the possible exception of Hurricane Sandy, there’ve been (thankfully) very few high-profile opportunities to test new forecast systems in the last 10 years. The U.S. is in the midst of a record-breaking drought of hurricane landfalls with winds of 111 mph or higher—“major” hurricanes. We’ve grown complacent, and sooner or later, our luck will run out.

I can guess what will happen then: There’ll be an ominous forecast cone, worryingly camped over a major coastal city for a few days. Officials may wait until the day before to order mandatory evacuations, and many locals might choose to stay. After the stormwaters recede, the damage will be measured in the tens of billions. People on the evening news will say, “We never saw it coming.”

Just this week, on Twitter and in weather message boards, I’ve noticed Floridians confidently quip something like: “If we’re in the cone at five days, I know I can breathe easy. We never get hit when the storm is pointed at us that far out.” NOAA, to its credit, is gently challenging that narrative this month.

Still, at this point, there’s reason to believe that better forecasting isn’t the most important thing in minimizing American losses to hurricanes. Providing two or three extra days of warning may not mean much for low-income families whose evacuation options are limited, as Katrina painfully showed. In a recent op-ed, Peter Neilley, the scientist in charge of forecasting operations at the Weather Channel, said that when preparing for the next major hurricane, psychology is now as important as meteorology. In Katrina, “there was a gap between the perceived accuracy of the forecast and the real accuracy,” Neilley wrote. “Society’s perspective on forecast accuracy lagged behind the true gains that our science had made up until that point.”

The same is true now. Even with perfect forecasts, society can never be perfectly prepared for extreme weather. Only when meteorologists and emergency managers place the “why” of improving forecasts above the “how” will society truly benefit. This is a lesson that the meteorological community is still struggling to learn. That’s why after Katrina, after the horrible tornadoes of 2011, after Hurricane Sandy, we all asked, “How could this happen?” At some point, improving society requires a re-think of why people become vulnerable in the first place, and then taking action to ensure those vulnerabilities are addressed. Better weather forecasts help, but what we need is a better society that prevents those vulnerabilities from reaching potentially disastrous levels in the first place. Many meteorologists are already thinking this way, but we’ll need a whole lot more before we can say we’ve made progress since Katrina.