An ongoing, largely successful effort to accelerate improvements in hurricane forecasts has been cut significantly, and meteorologists aren’t happy about it.

The Hurricane Forecast Improvement Program is a 10-year initiative that launched in 2010, and it’s designed to enhance scientists’ ability to anticipate rapid fluctuations in track and intensity for tropical cyclones, which routinely rank among the costliest and deadliest storms on Earth. In its first five years, HFIP has produced a state-of-the-art hurricane forecast model that’s helped to improve hurricane forecast accuracy by 20 percent since 2010, among other achievements. That’s amazing progress, essentially making a five-day forecast as accurate as a two-day forecast was just 10 years ago.

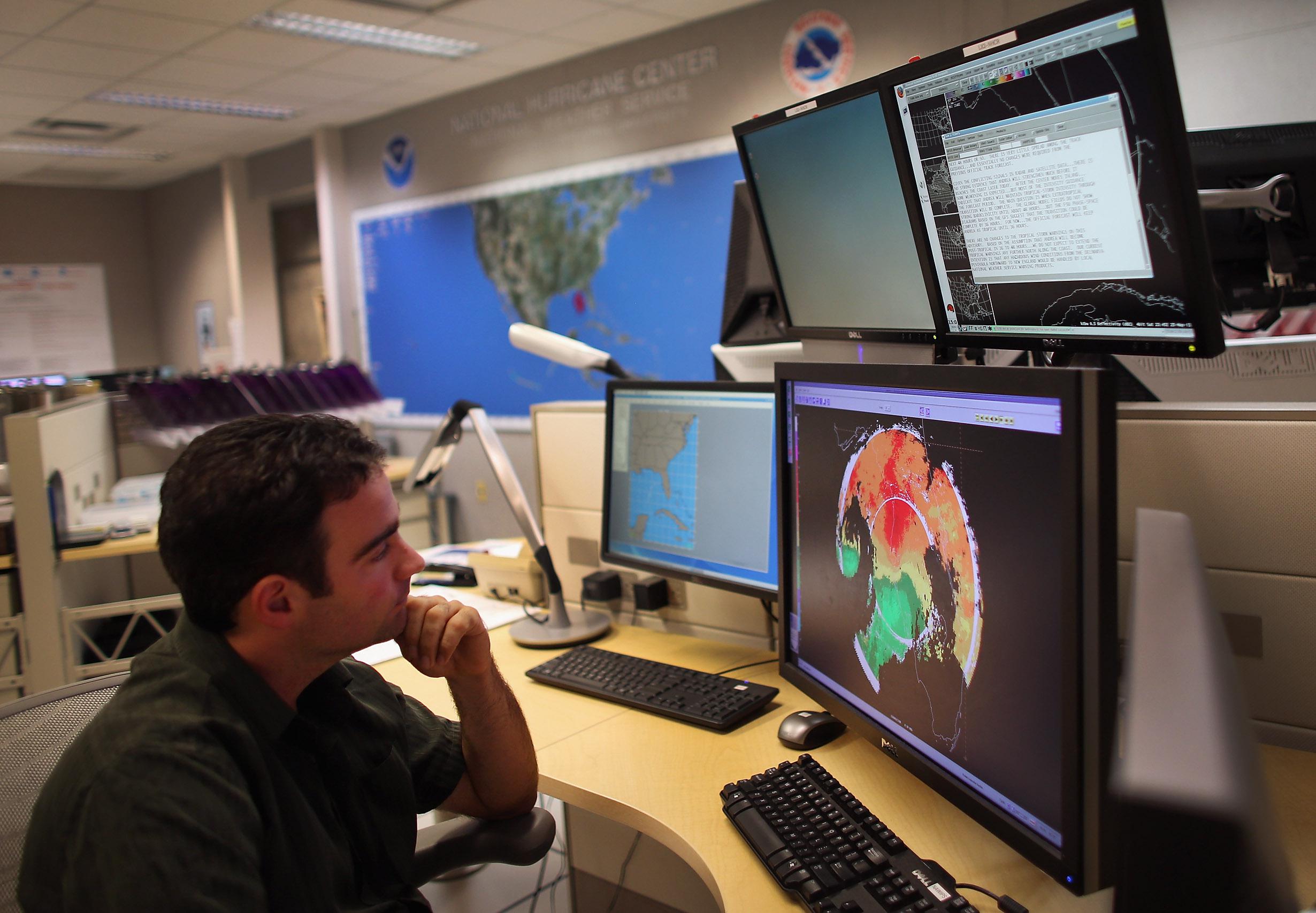

Now, the program is apparently a victim of its own success. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration cut the program’s base funding for the current fiscal year by about two-thirds, to $4.8 million from $13 million, in an attempt to refocus on “immediate, key needs” rather than longer-term goals.* Because of the cut, NOAA estimates that it will have to scuttle a target to further double the accuracy of two-day intensity forecasts from current levels over the next three to four years.

The cut was announced at the National Hurricane Conference in Austin, Texas, last week and was first reported by the Washington Post’s Jason Samenow on Tuesday

Chris Vaccaro, a representative for the National Weather Service, confirmed to Slate the cut will affect HFIP for the remainder of the 2015 fiscal year, which runs through Sept. 30. But despite the significant cut, Vaccaro says the program isn’t dead and is still producing useful science.

“It’s important to emphasize that there is still funding for HFIP, work is still being done and advancements will continue to be made,” Vaccaro said.

In 2015 the program’s hurricane forecast model is actually getting an upgrade, though the program’s partnerships with university scientists may take a hit. Vaccaro also notes HFIP has access to an additional pot of $4 million this year for supercomputing resources, which wasn’t affected by the cut.

But HFIP would have had access to that money anyway, so it doesn’t really make up for the $8 million in cuts. That’s alarming. On average, hurricanes are the costliest storms in the United States and in many parts of the world, routinely killing hundreds or thousands of people in a single day. Disaster deaths are in a long-term decline in the United States and around the world, thanks in part to programs like HFIP—an incredible feat, considering more and more people are moving into harm’s way. As a result of the cuts, NOAA says warnings and evacuations will be less precise, a considerable inconvenience and cost to the economy. With billions of dollars on the line, it’s hard to figure how it makes sense to save $8 million with this move.

Hurricane-focused meteorologists say the most disheartening thing about the budget cut to HFIP is that NOAA is giving up on longer-term goals. Of the dozen or so meteorologists I contacted, reactions included shock and incredulity:

Eric Blake, a forecaster at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center: “It’s hard to believe this is a good program to slash funding when it appears to be working. I understand budget tightening, but a cut of two-thirds seems extreme.”

Kerry Emanuel, hurricane researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: “I do not know what kind of politics is responsible for this, but the decision clearly does not serve the interests of our country.”

Marshall Shepherd, past president of the American Meteorological Society and host of WX Geeks on the Weather Channel: “Shocking … undeniably hurricane track improvement translates to lives and dollars saved. It is shortsighted to stunt this progress and hinder potential improvement in intensity forecasts. We can’t continue to be a culture that cuts progress, then panics only after a horrific tragedy.” Shepherd is referring here to a recent significant increase in funding for NOAA supercomputers after the National Weather Service forecasts for Hurricane Sandy were seen as lacking in accuracy.

Nate Johnson, a TV meteorologist in North Carolina, the last state to experience a hurricane landfall: “The cuts are disappointing, especially since the program has already led to improved forecasts, with the promise of continued improvement. I can’t help but wonder if the recent drought in Atlantic hurricanes contributed to a sense we don’t need to invest in improving forecasts for future storms.”

As of Wednesday there hasn’t been a major hurricane landfall (defined as a Category 3 or greater) in the United States for a record 3,453 days—nearly 10 years. With a building El Niño in the Pacific, which typically brings weak Atlantic hurricane seasons, that streak has a good chance of continuing this year.

But surging coastal populations in places like Miami as well as steadily rising sea levels are combining to set the stage for an eventual calamity.

Call it complacency or an unfortunate consequence of a tight budgetary environment, but programs like HFIP are exactly the opposite of what we should be cutting.

*Correction, April 8, 2015: This post incorrectly misstated the base funding for HFIP was cut by more than two-thirds. The budget was cut from $13 million to $4.8 million, which works out to 63.1 percent, which is slightly less than two-thirds.