The Fifth Obstacle to Sensible Eating: Inertia

External obstacles — confusion , money , time , and outside influences — are real, but there is no greater obstacle to change than our own inertia. If we are sufficiently motivated to change, it doesn't matter what our external obstacles are, but if we are truly resistant to change, it won't matter how much time, money, or support we have.

Our habits and inclinations come from various places. By nature, humans are hardwired to eat certain things. We are attracted to highly caloric foods — fats and sweets — because our species survived periods of hunger and scarcity, and our bodies adapted to attract us to the foods that would keep us alive. Of course, this attraction has outlived much of its usefulness.

And then there are the propensities we get from our upbringing. Much of what we know and do foodwise comes from the people who raised us, when we were raised, and where we grew up. My family was Jewish — of Russian, Polish, and Lithuanian descent. My parents were not religious and did not want to impose religion on my sister and me, but the cultural heritage remained. We ate the amazing cooking of my Great-Aunt Anne: chicken soup with matzo balls, brisket, stuffed cabbage, sweet and sour meatballs, chicken a la king.

My father was born shortly before the crash of 1929, my mother shortly before the start of World War II. He lived through the Depression, both of them lived through war; they witnessed the Holocaust. My sister and I were of the "clean your plate" generation, the "children are starving in Africa" generation. We were lucky to have food at all.

I was raised in the '70s and '80s. Instant foods were relatively new and something of a luxury. My mother could cook, and did, but she worked full-time, so convenience foods helped. For breakfast, my father warmed frozen honeybuns in the toaster; my sister and I ate sugared cereals or toast with margarine and Smucker's. The toast was Wonder Bread. The milk was whole. The coffee was Maxwell House instant (in fact, I didn't know what non-instant coffee was until college) with light cream. My father made pancakes from scratch on Sundays and baked his "famous" chocolate cake on special occasions. The flour and sugar were white.

On weekdays, we bought lunch at school. On weekends it might be a sandwich of cold cuts and mayo or mustard, store-bought potato salad and cole slaw; or maybe Campbell's Chicken and Stars or Tomato soup; or a hamburger or hot dog with mustard or ketchup or sweet green relish; or maybe tuna fish or peanut butter and jelly. My sister and I enjoyed the canned entrees of Chef Boyardee.

Dinner was a meat, a starch, and a vegetable, usually from a can or from the freezer. The meats were roast beef, steak, chicken, sometimes ham, London broil, ground beef with B&M baked beans, hamburgers, minute steaks, cube steaks, pork chops. The pasta was Prince spaghetti. The sauce was Ragu. A typical dinner during the week might be chicken parts baked in a pan with a can of Campbell's Cream of something soup thrown over it. Potato Buds or Uncle Ben's converted rice might be the starch or even egg noodles with gravy, or canned boiled potatoes. A vegetable might be canned corn (even creamed), peas, or green beans or a Boil-n-Bag something or other from the freezer. My mother used Shake-n-Bake, and I helped.

This menu was not uncommon fare at the time and was not considered unhealthy.

Even later, when we introduced salads, the lettuce was iceberg, the tomatoes were pale pink and hard and came in a cellophane-wrapped three-pack. The dressing was Ken's Italian, creamy Italian, Seven Seas Green Goddess, or, on rare occasions, blue cheese.

We also went out to eat frequently — two to three times per week — and Chinese food was a staple. It was Cantonese when I was young, then Szechuan/Mandarin when I was older. We went out for Italian, Greek, seafood. We ate fast food: Pewter Pot, IHOP, Pizza Hut, McDonald's, Kentucky Fried Chicken, York Steakhouse, Friendly's. Summers we spent in Maine, which added to our repertoire: lobster, blueberry pie.

Dessert was Friendly's ice cream, cookies, cake, pie, or Jell-O gelatin or instant pudding. And there was always dessert. My parents weren't strict. I don't much recall them telling me I would ruin my supper (yes, we used the word supper ). We were deprived of nothing, but we were not gluttonous. Everything ordered was small, never large or even medium. At restaurants we each had one dinner roll with one pat of butter. Salad dressing was drizzled on top, not a coating for both sides of every leaf. Sodas were the typical drink, not even an issue.

Even within the same family, we had our own inclinations. My father was skinny and finicky. He liked his beef and he didn't like to try new things. My sister took after him. She liked her steak well-done and only the white meat of poultry. She'd carefully dissect her food before eating it. At the end of the meal she'd have a neat pile of scraps at the edge of her plate. I took after my mother. I tried and liked everything. I liked my steak rare — the redder the better — my chicken and turkey meat dark . I ate the skin. I took seconds, thirds. I was born a member of the clean-plate club.

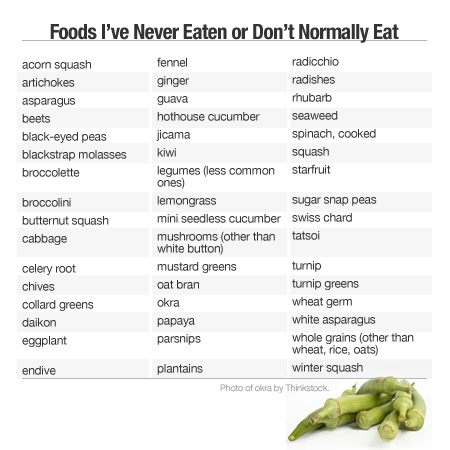

There were also foods we never ate at home. I don't recall ever eating spinach in my parents' house. Or asparagus. I had never heard of chard, kale, or kohlrabi. Consequently, there were foods I never developed a taste for — leafy greens, spicy foods — and others I grew too fond of: sugar, chocolate, beef. When I went to Chinese restaurants years later with friends, I never even saw the spicy dishes printed in red on the menu because I was so accustomed to skipping right over them.

Registered dietitian Dana Angelo White told me her nutrition clients either eat as their parents did or they do the opposite. It can be hard to change when your taste buds were formed by the foods your parents liked. For many years my concept of a meal was meat-starch-vegetable-dessert. When I married a vegetarian, it took a long time to figure out what I could make that we both would like. I ended up eating as my husband does for many of those years (but let's not confuse "vegetarian" with "healthy"), but whenever I got sick, tired, especially hungry, I'd revert to my default way of eating. This is what we get from our upbringing: default behaviors. And these are the behaviors we return to.

We eat certain foods because we like and are accustomed to them. Without them we don't feel satisfied. A morning without a cup of coffee doesn't feel quite right. A dinner without meat might not feel like a meal at all. A day not topped off by a sweet dessert might feel incomplete.

Some of us live in mortal fear that the things we like will be taken away. This is why we binge the night before going on a diet. This is why diet advertisements tell people what they can eat instead of focusing on the weight loss.

Of course these are just habits, and habits can be changed, right? Some " experts " actually offer numbers for how many days it takes to form, change, or break a habit . This is absurd. I've changed habits for months, entire years even, and then reverted. I tried to be a vegan for nine months and then one Thanksgiving, I ate turkey, and that was the end of veganism. One year I worked out for two hours a day. No more. For two years I rose between 5 and 6 a.m. to write before work. And then I stopped.

In some cases it's a matter of finding the right motivation. When I was in college I smoked cigarettes. I always felt it was a disgusting, unnecessary habit that pointed to some moral failing on my part. You know how it goes: I quit and I started and I quit and I started for years and years and years. I, of course, knew about the health issues: I'd seen films in school and television ads showing black, shriveled lungs. Nonetheless I could never quit for good until I found the right motivation, which was, oddly, money. Smoking was too expensive. (Hilariously, when I started smoking, cigarette prices had reached about a dollar a pack and when I quit they were about $2.) Whenever I craved a cigarette, the only way I could keep myself from buying them was to tell myself it was too expensive. I don't know why this worked — maybe because I am a cheap-ass from a long and proud line of cheap-asses — but eventually it stuck.

But you can't quit food completely; you have to have "willpower." While on an organized diet, I was offered advice about how to deal with cravings, which essentially consisted of substituting a "healthier" choice (e.g., a glass of skim milk) for the food I wanted (e.g., a Strawberry Frosted Pop-Tart — or two), distracting myself by getting involved in an activity, or simply waiting the craving out. If I just waited — if I just had willpower — I was promised, the craving would go away. But it never did. I was capable of craving chocolate nonstop for three days — until I finally broke down and had some, because I just couldn't take it anymore. When I crave, my brain offers up images of food to entice me to eat, and it doesn't quit until I listen.

A study at Duke University conducted by psychology and neuroscience professor Wendy Wood found environment to play a much bigger role in changing habits than willpower. Our routines and environments cue us to have certain desires at certain times and places and to perform specific behaviors. Our triggered response overrides our willpower.

Change is hard. Change takes work and awareness and thought, and it's much easier to go about your day and do what you normally do. Regular life is difficult enough.

So what can we do to confront our habits? I've addressed some of this in previous weeks. I've worked on getting nutrients in , spending less money , eating mindfully , and avoiding temptation . This experiment is about broadening my palate beyond what my parents taught me.

Experiment No. 5: Trying New Foods

This is the week I face my food inertia.

Each week, I tend to buy many of the same foods (apples, bananas, oranges), avoid the same foods (leafy greens), and overlook foods I'm not so familiar with (celery root, guava, papaya).

So this week, only two rules: I cannot buy the foods I normally buy; and I must buy and try foods I've either never eaten or don't normally eat.

Below is a list of some of those foods. Please suggest others to me. Also, feel free to include recipes and/or instructions. I have no idea how to eat an artichoke aside from dipping each leaf into a vat of clarified butter.

Also see our Magnum Photos gallery on weird and funky foods .