In 1960, with the publication of her first novel, the Alabama-born Harper Lee taught a country of rapt readers that to kill a mockingbird was a sin. Mockingbirds don’t do one thing except make music for us to enjoy. The birds were radically pure, and their deaths numbered as small tragedies.

Over the next half-century or so, To Kill a Mockingbird received a Pulitzer Prize, inspired comics and videogames and rock bands, insinuated itself into high school curricula nationwide, and flew onto the silver screen, where Gregory Peck immortalized the character of Atticus Finch, a soft-spoken and virtuous lawyer who defends a black man wrongfully accused of raping a white woman. The novel melded urgent social commentary with the wry coming-of-age tale of Scout Finch, Atticus’ daughter. Scout—a scrappy tomboy with a caustic streak reminiscent of Lee’s own—learns empathy for the marginalized and pity for the innocent. The black man, Tom Robinson, is convicted by an all-white jury.

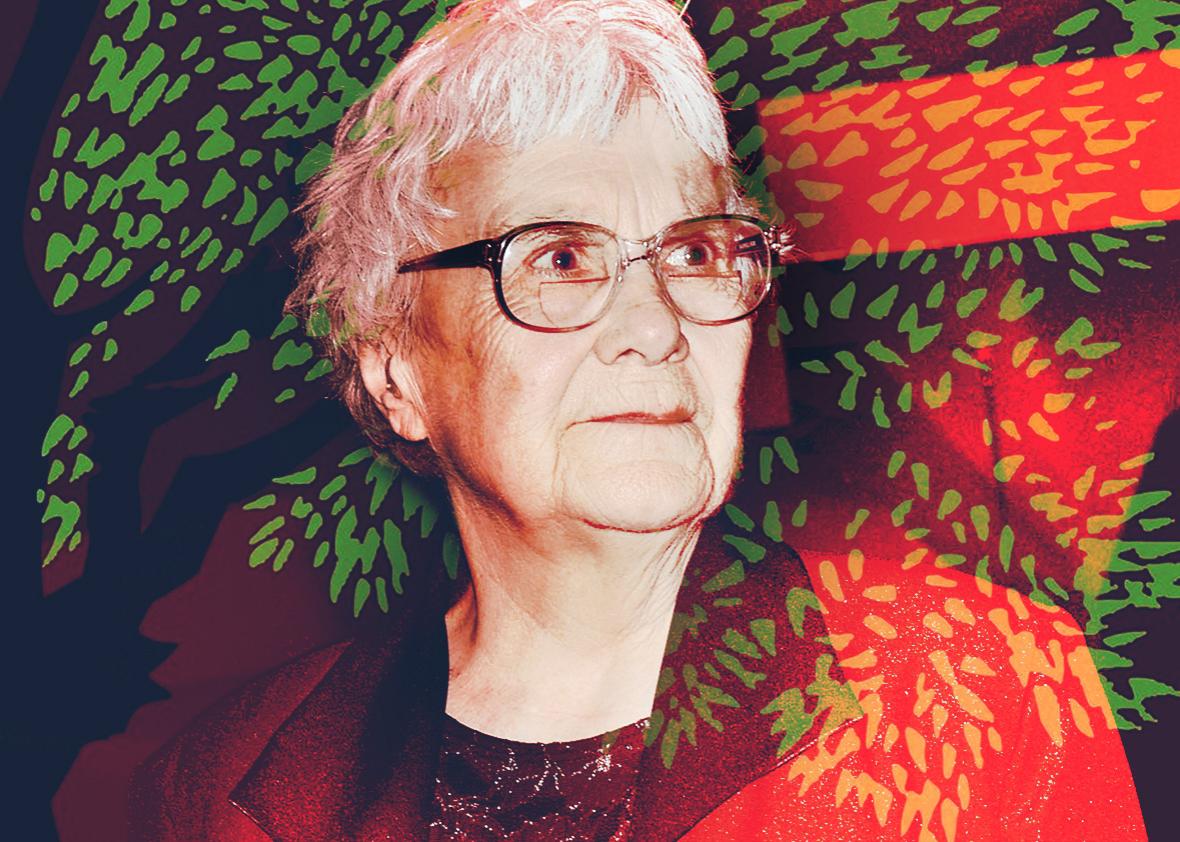

Shortly after publishing To Kill a Mockingbird, Lee retreated from public life, turning down interviews and moving from New York back to her languid hometown of Monroeville. Her legacy was pure, as uncomplicated as her stirring only book, as clear as a mockingbird’s call.

And then, suddenly, in February 2015, HarperCollins announced that an old manuscript of Lee’s—a prequel of sorts to Mockingbird, featuring a grown-up Scout—had been discovered in a vault. Amid the anxieties and protests of fans who feared that Lee’s lawyer/estate executor was taking advantage of her waning faculties, Go Set a Watchman arrived in July (and promptly sold more than 1.6 million copies.)

What followed was a sort of collective disenchantment, or an interlocking series of disappointments: In Watchman, Scout returns to Maycomb and realizes that, where race is concerned, her brightly principled father has feet of clay. (A sample line from Bigoted Atticus: ““Do you want your children going to a school that’s been dragged down to accommodate Negro children?”) Readers seduced by Mockingbird revisited Maycomb, too—and encountered uneven prose, bumpy pacing, a rambling ending. Just as a Scout propped up by Atticus-worship had to come to grips with her father’s weaknesses, so too did a literary canon propped up by Harper Lee-worship have to reorganize itself around the fresh imperfections in the beloved author’s façade. Arguments that Mockingbird had trafficked in simple stereotypes and white savior myths gained new ground. Others lamented the complicated, searching novel that Watchman might have been.

It was all sad, and—here is the funny, almost unearthly, part—all utterly of a piece with Lee’s philosophy as a writer. Forget the likelihood that Watchman was never meant to see the light of day. Lee believed that people have within them both flaws and veins of brilliance, that time’s tides erode innocence and deposit experience. In Watchman, Lee’s antennae for humanity angled toward Atticus, regarded throughout Scout’s upbringing as a demi-god and only later revealed to embody the prejudices of his era. In Mockingbird (which many speculate to be the final draft of Watchman, hammered into shape by editor Tay Hohoff) that same awareness found a form that was perhaps easier to swallow, but no less powerful: empathy for the imprisoned black kid, or the lanky shadow in the weird haunted house.

Now Lee has died in her sleep at the age of 89. Why does her death touch us so acutely? Contra the lessons of Mockingbird, it’s not because Lee only summoned forth flawless songs. Both her heartstopping passages (of which there are many) and her workmanlike ones (of which there are just as many) set out to demonstrate our shared humanness. With her fractured legacy, Lee’s more like the mockingbird in the Kay Ryan poem—“emperor of parts, / the king of patch”:

Nothing whole

is so bold, we sense. Nothing

not cracked is

so exact.