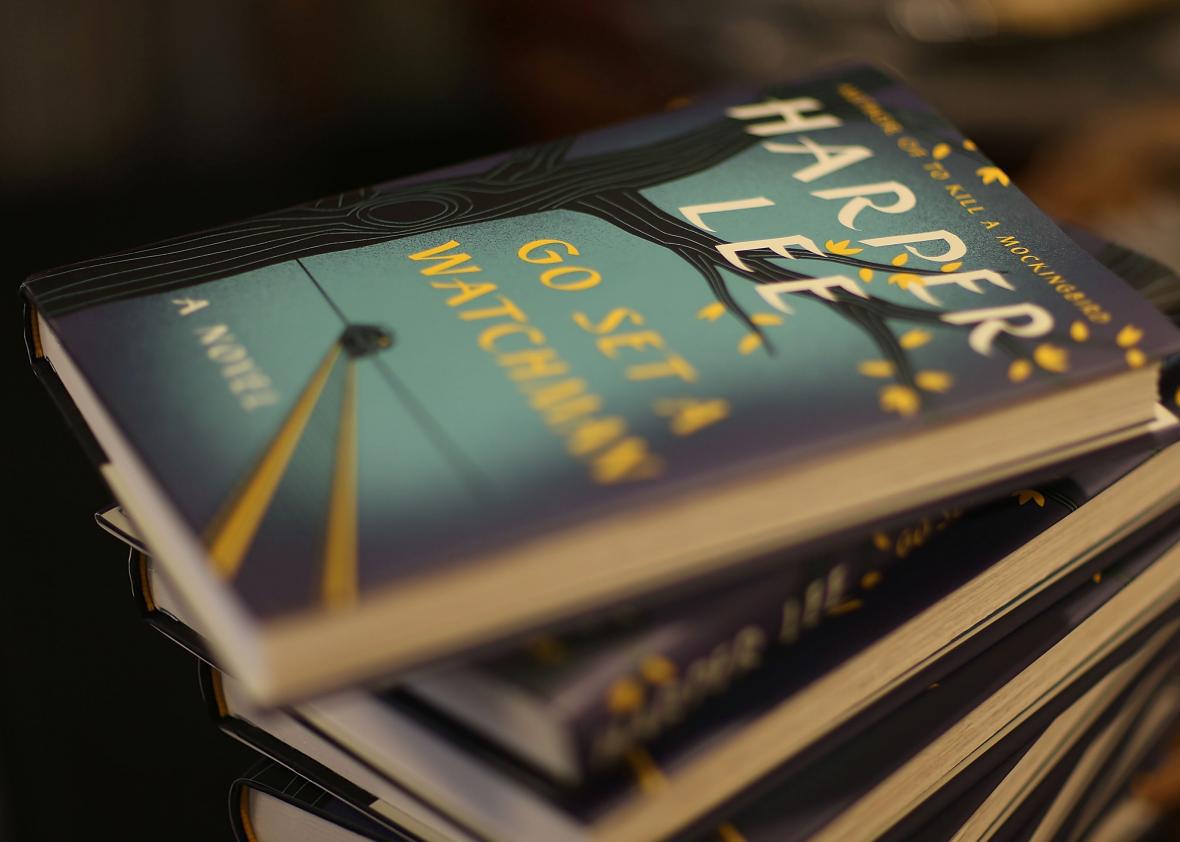

Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman has arrived to disturb and disenchant us, an unedited draft (unless you consider To Kill a Mockingbird the edited version—and passages airlifted from one book into the other nourish that theory) released under queasy circumstances. Reviews have already touched on the new novel’s stiltedness; told in the third person, it hasn’t yet discovered the fluid immediacy of Scout’s voice. Conversations can sound like academic debates brined lightly in regionalisms. (“Hell … I’m a healthy old man with a constitutional mistrust of paternalism and government in large doses.”) Chapters wander off like dairy cows—you can skip the section on a Methodist church service, and skim many of the scenes with love interest Henry Clinton—and various themes get poked, confused, abandoned. Jean Louise, once a tomboyish rapscallion, has had to wrestle herself into womanhood: There are fascinating but underdeveloped nods to menstruation, sexuality, gender performance, and feminism. Flashbacks from Jean Louise’s childhood are vivid and funny (so much so that you understand why Lee’s editor, Tay Hohoff, encouraged her to shift her focus to the younger, wilder Scout the second time round), but unintegrated, as if Lee wished to strand the past on a charmed, inaccessible island.

The book has its share of graces. Jean Louise, independent, stubborn, sarcastic, does more than satisfy our curiosity about what a grown-up Scout might look like—she’s right wonderful to follow. You sense some of Harper Lee’s own rebelliousness and humor in her; as with Mockingbird, author and character seem beautifully intimate with one another. A set piece in which Jean Louise entertains the preposterous corseted meringues who make up Maycomb’s lady society is delicious, all acid-tipped niceties and suppressed boredom. Another scene—Scout’s failed reunion with her black housekeeper Calpurnia, who is suddenly and devastatingly closed to the white woman on her doorstep—is almost a reversal of the empathic connection Scout made with Boo Radley in Mockingbird. Even the clumsy, ellipsis-ridden torments that run through Jean Louise’s head (“He kills me and gives it a twist … how can he treat me so? God in heaven, take me away …) feel like less-controlled rehearsals for younger-Scout’s fervent inner monologues. Which is to say: Behind every misstep glimmers the eventual course correction.

But I’ll cut to the chase, because the thing most people are agonizing over, at least since Friday’s New York Times review, is Atticus.* In Mockingbird, of course, Jean Louise’s father (seared into our corneas and souls by Gregory Peck) represented the town’s saintly, moral heart, a lawyer committed to “equal rights for all and special privileges for none,” a staunch believer in racial equality. He couldn’t save Tom Robinson from prejudice, but he tried. Whereas in Watchman, also a story of lost innocence, not only has Atticus managed to acquit Robinson, he is a bigot who chairs “white citizen’s councils,” supports segregation, and sympathizes with the Klan. Uncovering his hateful views pamphlet by pamphlet and meeting by meeting sends Jean Louise into crisis. Between Mockingbird and Watchman, Lee has rescaled her hero’s disillusionment, transferring it from the realm of society to the more intimate level of character. Maycomb hasn’t really failed Scout—her dad has.

The toppling of Atticus as a moral icon feels attractively modern and nuanced—and true to this ambivalent racial moment, in which white police officers can gun down black teenagers, but we’re beginning to perceive the poison stitched into the Confederate flag. Written in the ’50s, Watchman also aligns with the contemporary impulse to complicate and undermine our idols. (Think Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy or the storm of antiheroes on prestige television.) Here are some things Atticus says:

“Honey, you do not seem to understand that the Negroes down here are still in their childhood as a people.”

“We’re outnumbered, you know.”

“Do you want your children going to a school that’s been dragged down to accommodate Negro children?”

“Can you blame the South for wanting to resist an invasion?”

Yet, for me, making Atticus a brightly principled character in To Kill a Mockingbird did a better job of emphasizing racism’s horror. Watchman’s focus on universal human frailty seemed jaded and stale—less compelling, at least, than the first book’s image of virtue flashing forth, then extinguished, again and again and again.

Atticus’ fall and partial resurrection in Watchman feels … off. The watchman in the title comes from a biblical verse, where it figures the human conscience. (“I need a watchman … to draw a line down the middle and say here is this justice and there is that justice,” Jean Louise broods.) Atticus, too, is introduced as a “watchman”—he’s literally a man who “wore two watches … an ancient watch and chain his children had cut their teeth on, and a wristwatch.” Morally, then, Atticus has a doubleness about him. (You could call it hypocrisy, if you wanted to be uncharitable; Lee would probably prefer contradictoriness.) And much of the novel’s drama flows from Jean Louise’s struggle to stop worshipping her father as an infallible light, to “reduce him to the status of a human being,” as her uncle puts it, and love him despite his flaws and inconsistencies.

Yet coupled with the Atticus-as-watchman motif is a recurring metaphor about Jean Louise’s blindness. “I never opened my eyes,” she grieves toward the end of the book. She’s not talking about failing to see her father’s politics clearly—she means that she’s been too stubborn to cast off her own ideological blinkers. This has prevented her from embracing Atticus and his imperfections. But … should she? As Scout’s uncle explains to her, “you’ve never been prodded to look at people as a race, and now that race is the burning issue of the day, you’re still unable to think racially.” What if our hero’s specific, naive, troubling form of blindness is colorblindness? Shouldn’t everyone else’s vision be corrected? Lee’s sympathies apparently lie with Dr. Finch, a “truth-telling” eccentric who steers his niece toward enlightened tolerance via poetic parables and mild, Socratic queries. But modern readers may wonder why Jean Louise needs to spend so much energy learning to see eye-to-eye with bigots.

What’s especially insidious about Lee’s outwardly lovely message of reconciliation and empathy (which also animates To Kill a Mockingbird) is the way it syncs up with Lost Cause romanticism. “Has it never occurred to you,” Dr. Finch asks his niece, patiently guiding her toward open-mindedness once more, “that this territory [the South] was a separate nation? A society highly paradoxical, with alarming inequities, but with the private honor of thousands of persons winking like lightning bugs through the night?” (This to explain Atticus’ participation in the racist citizen’s committee.) “No war was ever fought for so many different reasons meeting in one reason clear as crystal,” Finch continues. “They fought to preserve their identity.”

But self-actualization myths aside, they, the gray-clad army, fought to preserve slavery. And when Jean Louise’s uncle declares that “what was incidental to the War Between the States”—e.g. the fate of black Americans—“is incidental to the issue in the war we’re in now”—e.g. the Civil Rights Movement—I felt ill. It was as if, in crafting a moral arc for Scout that went from dogmatism to loving acceptance, Lee was signing off on a vision of the Civil War as a noble clash of empires, each worthy in its way. In the wake of intrafamilial tragedy, the book suggests, echoing Lost Cause talking points, what matters is not petty differences of opinion but restoring unity. Rescuing Atticus as a moral force, as a compromised but beloved part of Scout’s past, almost registers as a small Confederate redemption.

Of course, Lee, born in 1926, is a product of her time. And she weaves in plenty of stirring language about the fundamental humanity of all people, black and white. But Jean Louise also reflects, “I did not want my world disturbed, but I wanted to crush the man who’s trying to preserve it for me. I wanted to stamp out all the people like him. I guess it’s like an airplane; they’re the drag and we’re the thrust, together we make the thing fly.” Would the Atticus of Mockingbird agree that bigots help keep the aircraft of state aloft?

Speaking of that beleaguered Atticus, I reject the notion that he has to answer to Lee’s new book (which smells like a discarded draft of Lee’s old book). The Atticus in To Kill a Mockingbird is a fortress, a living literary creation, and from what I remember of the vitriol slung his way when he took up Robinson’s case, he’s endured far worse. Go Set a Watchman, which neither tarnishes Mockingbird’s legacy nor changes its meaning, enlists familiar characters in a painful thought experiment. The results are just that: shards of speculation, provocative, worthwhile, and sad.

*Correction, July 15: This post originally misstated that the New York Times review of Go Set a Watchman was published on July 13. It was published on July 10.