Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird became iconic almost immediately after appearing in 1960: best-seller status; the Pulitzer Prize the next year; a classic movie soon after, with Gregory Peck in an Academy Award–winning role. It has since gone on to sell more than 40 million copies in umpteen editions, and has become obligatory on high school reading lists (which also means it is widely banned). The copy I picked up recently references the original cover art but the flap copy no longer describes it as a novel—instead, it is “one of the best-loved stories of all time,” for once not an exaggeration. The very idea of its being a “story” preserves Mockingbird’s Southernness—a tale told, and well—while transforming it safely into a kind of universally known folklore.

Or was it always just a coming-of-age book? Despite the book’s success, or perhaps because of it, Lee’s fellow Southern writer Flannery O’Connor saw it as kid’s stuff; in her archives at Emory University, where I am the curator of literary collections, O’Connor dismisses Mockingbird as “children’s literature.” In his groundbreaking Love and Death in the American Novel, critic Leslie Fiedler argues that classic American novels—from Huckleberry Finn to the Leatherstocking Tales—are “notoriously at home in the children’s section of the library, their level of sentimentality precisely that of a pre-adolescent.” He means that there’s a certain prepubescent innocence in American literature, once devoid of women except as puritan ideals, but that this innocence married to Gothic horror created the power and paradox of our literature. I would go further: like Huck Finn, children’s literature speaks not just to a book’s young characters and readers but a relatively young country wrestling with a tangled history of race and caste.

For Mockingbird changed literature, especially children’s literature. Fiedler’s provocative comment that “our classic literature is a literature of horror for boys,” though published the same year as Mockingbird, seems out of date exactly because of Mockingbird’s success. Harper Lee’s debut almost singlehandedly invented the category of “young-adult” fiction—we could not be luckier that the genre’s chief example depends on such a thoughtful book for which beauty is a best friend and race, ladyhood, and justice all share time on the front porch. These days Mockingbird has become so influential, even ubiquitous, that celebrities name their kids after the “tomboy” narrator Scout—she has become an American icon, a fictional character like Jay Gatsby, Tom Sawyer, or Holden Caulfield whom people treat as real.

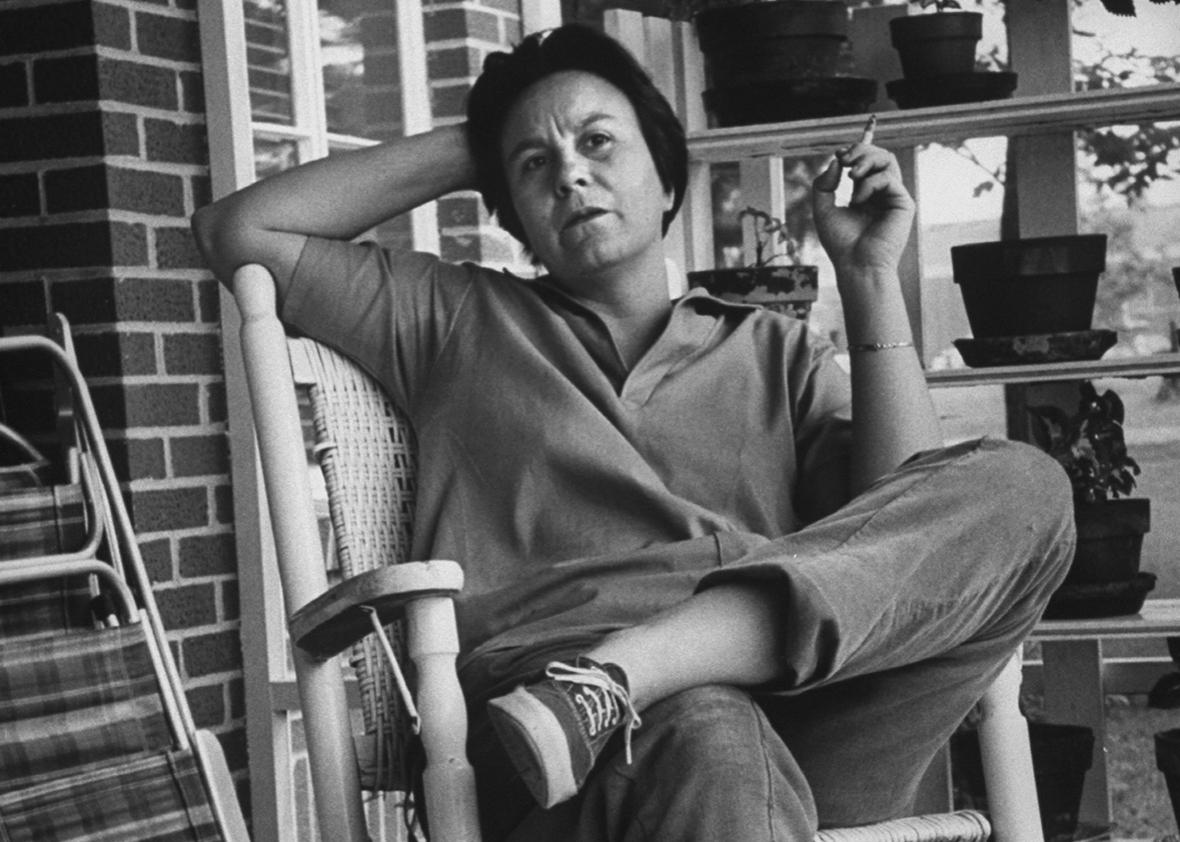

Lee herself has joined the ranks of American classics: like Ralph Ellison, she wrote a near-perfect novel universally recognized but, the story went, never could or would finish another; like J.D. Salinger, Lee walked off the public stage and hasn’t give us more words though we thought them our due and her duty. Her publishing silence over the past 55 years also calls to mind other Southern and “near-Southern” writers, gone too soon, sometimes by their own hand, whose work lives on in A Confederacy of Dunces and The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake. Like Mockingbird itself, the many tales about the book’s author veer between everyday insight and grand speculation, Southern to the bone.

This has led to some strange misperceptions, or at least oversimplifications. Lee is seen more and more as a childlike recluse, when she is by all accounts a sophisticated presence, though certainly private. This we cannot reconcile. Rather than the plucky protagonist Scout, or the understanding and patient father and lawyer Atticus Finch, Lee gets treated as if she is her other memorable character, Boo Radley, who won’t ever come out and play. She too has become an icon literally hard to see—at least till recently.

Rereading To Kill a Mockingbird, I was struck by what I had forgotten of the book: in a manner of pages we encounter shame, history, ruin, conflicting stories, and wounds badly healed; in short, the South. Though set in the Depression, Mockingbird actually spoke to the civil rights movement during which it was published. Read now, it seems oddly current, the best definition of a classic.

“They’ve done it before,” Atticus says after his black client is wrongly convicted by an all-white male jury, “and they did it tonight and they’ll do it again and when they do it—seems that only the children weep.” Scout’s naiveté and her older brother Jem’s disappointed tears prove crucial here. The reader becomes another neighbor, knowing much more of the story than Scout can tell us (or that we can reveal to her or otherwise ourselves). At the same time, we learn alongside Scout the mores and failings of Maycomb, Alabama, and the South with its lost causes and mysteries and maintained manners; the book invokes bravery almost as much as the N-word. It is to Lee’s credit that I hardly had recalled the amount of racism thrown about by characters we might otherwise admire—racism in the book is a form of confusion as much as anything, with Scout fighting her cousin who calls her lawyer father “a nigger-lover” though she doesn’t quite know what he means. It’s how he said it, she explains. By the time she asks her black maid Calpurnia and Atticus what rape is, we’ve left any typical children’s book behind.

For race is the true protagonist of the American novel. Our most popular classic fictions have known this, from Moby Dick to Beloved; all these books take on race or talk it out, often in other forms; they are less “horror stories for boys” than ghost stories from a haunted conscience. The South’s heroes are all either saints or martyrs. Suffering is part of the landscape, as seen in Mockingbird through mean old Mrs. Dubose who hurls abuses and insults at the children from her porch but decides to kick morphine at the last and finds dignity in a natural, if painful, death. In a world of defeat, dying on one’s terms can seem the most heroic of acts—even if it suggests another kind of “Lost Cause.”

* * *

This week’s release of Go Set a Watchman, Lee’s second book—a story written first but with its action taking place decades after, shelved for years and only recently uncovered—is more anticipated and dreaded than Boo Radley’s emergence from his haunted house. How does one provide a sequel to a ghost story?

One way is to say it’s just a story, nothing to be scared of. Tales about Watchman abound, including the rather unconvincing and convoluted one from Lee’s camp—or at least her lawyer—of only finding the manuscript last year and putting it out now. Anyone who works in an archive as I do knows that most of the archive’s ghosts are well known; how could a semi-sequel to the most beloved book of our time, once submitted to a publisher who convinced her to tell its backstory first, remain completely unknown? It would seem books and biographies of Lee, like Charles J. Shields’s 2006 biography Mockingbird, regarded Watchman not so much as an early draft but a working title, much like the lawyers and the Sotheby’s appraiser did. (The lawyer has just this week changed the story again, making mention of a possible third book!) No matter the timing, the rediscovery (let’s call it) certainly shouldn’t be met with fire.

Some argue that existence of Watchman does not mean it should be published; others seem to wish it didn’t exist at all. I rather think that archives exist to keep things safe, but not secret. The author is not the only solution or last word as to what should emerge from the archive—or safe deposit box. I don’t mean here some radical notion about copyright, simply that editorial decisions are group efforts and exactly that, decisions; unlike a courtroom, a book’s editorial choices are not verdicts, at least not singular ones. (They shouldn’t be merely financial.) But unlike Scout in the first novel, who must accept that verdicts are made by flawed humans, we have become less and less comfortable with the tensions found in the archive and novel form alike. In both a novel and the archive the writing starts out singular, usually done by one person, even if amid a community of others; yet the reading of an archive is always multiple. The editing of a book, especially a first novel, is necessarily a team effort, and from what I’ve read of both Mockingbird and its process, the book would seem to have been well served. To Kill a Mockingbird’s success, not to mention its filming, suggest that the book and its characters have long been beyond one person’s control—even its very much alive author.

It might do us better to see Watchman as information, a document as well as a novel, one that it is better that the world see whole than leave to scholars to debate privately. Lee’s latest (and earliest) book takes up the characters readers and viewers have come to love and sets them 20 years later, in the midst of the Civil Rights movement. It feels apt that we share some elapsed time between the publications with a grown-up Scout. Like fictional Maycomb, we’ve grown but not quite outward, rather more and more inward.

Atticus has returned to us arthritic and older; Jem, as those who read the first chapter online before publication found out, is killed off abruptly in a sentence. As a literary work, Watchman’s first chapter may be its worst. But the book is more than apprentice work: in it we can find the shimmering voice and pointed tone that are Lee’s hallmarks. The text itself contains echoes, even exact ones, giving a sense of this as a draft—but hearing Aunt Alexandra (again) described as having “river-boat, boarding room manners” is like seeing an old friend long lost. There are also welcome flashbacks, such as a nice set piece with Dill (modeled on Lee’s childhood friend Truman Capote). Such reconnectings I found welcome and uncanny, reminiscent of the oral tradition.

What worries aren’t the echoes but the flat notes. Though many across the country lined up at midnight to get the first copies of Watchman at bookstores, including in Lee’s hometown of Monroeville where an Atticus Finch impersonator showed up too, some would say that the Atticus of Watchman is the true impersonator. Atticus Finch has long been not only the ideal of the Southern gentleman—a fair-minded one, seeking justice and despising those who’d take advantage of a Negro—but also America’s kindly father. (He’s also become Gregory Peck, and vice versa.) Like Jean Louise, the grown-up Scout, readers of the new (yet old) story have been shocked to learn the gentleman lawyer is on the Citizen’s Council. Such White Citizens Councils, often connected to the Klan, sprang up around the South after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Once again, we experience the world with Scout/Jean Louse; along with her, we are enraged or puzzled by Atticus as he now appears.

Yet should we be surprised? Atticus has always personified the paradox of whiteness in the South, a place where white supremacists regularly wave a separatist flag yet claim themselves patriots. (Such ironies became highlighted when the alleged Charleston killer Dylann Roof took selfies burning the American flag, while waving the stars and bars in other photos.) Still, it is hard to imagine the power of Watchman without the Atticus of Mockingbird we know so well, on screen and in the classroom—otherwise, the disappointment would seem merely symbolic, rather than as soul-crushingly personal as it becomes for Jean Louise.

“Sometimes, we have to kill a little so we can live,” says the once loveable Uncle Jack. The last third of the book devolves into extensive dialogue between the characters, which, while believable, is far more predictable than the quirks and complex lessons of Mockingbird. As the book’s white guys, and Aunt Alexandra, issue pat rhetoric about “states’ rights” and the influence of outside agitators, it can’t help but feel familiar—even recent, given select resistance to the Supreme Court gay marriage ruling. When we learn Atticus too joined the Klan, merely “to find out exactly what men in town were behind the masks,” it is hard to know what to trust, much less who. The characters’ whoppers like “A long time ago the Klan was respectable, like the Masons” belie the violence in the history of white supremacy, and in the language used to justify it.

Far more powerful foils for Jean Louise come with two fascinating parallels with Mockingbird: namely with the courtroom and with Calpurnia, the Finch’s maid. The fictional courtroom—its inspiration now a tourist attraction in Monroeville—has become redolent of Gregory Peck’s Oscar-winning closing argument and Atticus’s greatest triumph-in-defeat for his black client in his rape case. (There is, in Atticus, always something of the Lost Cause, though originally for justice.) Watchman mentions a similar-sounding, long-ago court case, down to the black man’s wounded arm, but one in which Atticus wins an acquittal, a story that can only feel perfunctory; in Watchman, Jean Louise sneaks into the courtroom’s “colored balcony,” this time alone, to eavesdrop on the Citizen Council. To see the courtroom turned into a bigoted executioner’s chamber is powerful indeed.

Afterward Jean Louise visits Calpurnia, echoing the time she accompanied her caretaker to AME Sunday service in Mockingbird. In Watchman, she’s ostensibly visiting after Calpurnia’s grandson kills the (white) town drunk in a driving accident; Atticus has agreed to take the case so the dreaded NAACP won’t stir things up. “Now, isn’t it better for us to stand up with him in court than to have him fall into the wrong hands?” he says. The book is filled with guilty pleas. Reeling, Jean Louise seeks out “her old friend” Calpurnia—not to comfort the grieving grandmother but to comfort herself, not for redemption but reassurance. Calpurnia’s subtle rebuff—“Calpurnia was wearing her company manners,” treating Jean Louise more like a stranger—becomes a stark gulf when the woman asks, “What are you all doing to us?” Jean Louise drives home, Scout no longer.

The book could have ended near there, exploring what it means for her to be “extravagant with her pity, and complacent in her snug world,” wrestling with race’s ambiguities or leaving them as conflicts. If so, the new book might be brave in ways Mockingbird, as a novel of childhood, could avoid; the innocence in it is not just Tom Robinson’s, but Scout’s too. (You could say in a bigoted world the book brilliantly lends him hers.) Yet while it charts “the malignant limbo of turning from a howling tomboy into a young woman,” Watchman is never quite able to maintain the dueling racial contradictions within the mind of adult Jean Louise, raised, as she realizes, “by a black woman and a white man.” It would take a book like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye to stay there at Calpurnia’s crowded house, to see beyond the front porch in ways Mockingbird first suggested. But Watchman ultimately returns to the strictest definition of family, and duty, as Jean Louise is supposed to. No wonder Jean Louise’s corseted, “enarmored,” elitist Aunt Alexandra becomes all the more prominent here. Is the aunt’s propriety ultimately what prevails?

Though set in childhood, Mockingbird is the more mature book, especially with its double perspective of the childhood Scout and the grown narrator looking back. Yet, for a time, Watchman proves quite moving when its language, and Jean Louise’s, changes after her colossal disappointments—filled with ellipses and regularly switching from a distanced third person to a closer narration, even regularly slipping into first person. For those near-brilliant middle chapters, we experience the “blight” alongside Jean Louise, who, “had she insight, could she have pierced the barriers of her highly selective, insular world, she may have discovered that all her life she had been with a visual defect which had gone unnoticed and neglected by herself and by those closest to her: she was born color blind.” This family trait is literal (and neatly echoes Mockingbird) but here means far more. Later she declares herself symbolically

blind, that’s what I am. I never opened my eyes. I never thought to look into people’s hearts, I only looked in their face. Stone blind. … I need a watchman to lead me around and declare what he seeth every hour on the hour. I need a watchman to tell me this is what a man says but this is what he means, to draw a line down the middle and say here is this justice and there is that justice and make me understand the difference.

For many, dare I say millions, Mockingbird has served to do exactly that. If only the rest of Watchman had such insight into the white segregationist mind and its justifications. For, as leaders like Martin Luther King suggested, segregation not only claimed black lives don’t matter and placed black bodies in jeopardy, but damaged what might be called the white soul. Perhaps with further vision and revision, Watchman could have testified to this. As is, it can never compete with Mockingbird but can’t help but be compared. But Watchman does press the question: Could Lee ever have written about such hate and remain as well loved?

—

Go Set a Watchman, by Harper Lee. HarperCollins.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.