Hey, have you heard this song, “Bad Blood,” that topped Billboard’s Hot 100? What a hater’s anthem! You have to marvel at the nerve of this pop star. The lyrics are a parade of she-can’t-be-trusted sneers; the music is lurching, glossy strut-pop; and the high-pitched chants in the chorus are all sass. And can we talk about the guest vocalist? He’s clearly the secret weapon—no way would this song have reached America’s top of the pops without him.

Kendrick? No—what chart-topping “Bad Blood” are you talking about? Because I’m talking about this one:

OK, so maybe Neil Sedaka’s radio-conquering team-up with Elton John (No. 1, 1975) hasn’t aged all that well. And it looks awfully basic next to Taylor’ Swift’s “Bad Blood,” which just reached No. 1 on the Hot 100 this past week—with major backup from Kendrick Lamar, widely regarded as the most talented rapper of the 2010s.

But Sedaka’s “Blood” has one or two other things in common with Swift’s, beyond its peak chart position, superstar assist, and bitchy lyrics. Both are, in their own ways, popcorn-movie–style blockbusters. Sedaka’s is Jaws: It came out in ’75, it was tooled for mass consumption, and the result was hugely successful if, in retrospect, rather primitive. Swift’s “Bad Blood,” on the other hand, is like Avengers: Age of Ultron: a cutting-edge, totally overhyped behemoth that used every trick in the book to draw eyeballs.

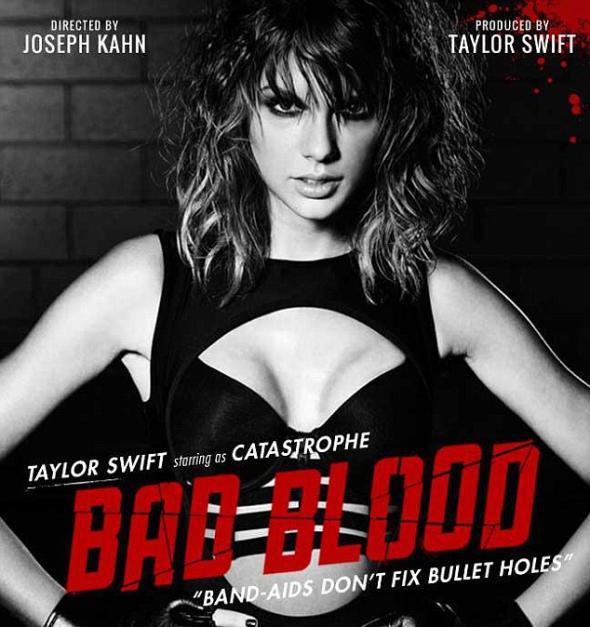

Like a modern summer blockbuster, Swift’s “Bad Blood” single was also given a heavily promoted May release date—complete with a series of Sin City–inspired posters—and the all-star music video premiered on the televised Billboard Music Awards. This worked like gangbusters: After re-debuting at No. 53 (the song had spent a couple weeks on the lower rungs of the chart before it was released as an official single), “Bad Blood” shot all the way to No. 1 a week later—evicting a song from an actual movie blockbuster, Furious 7’s “See You Again” by Wiz Khalifa and Charlie Puth.

In short, it took an army to make this fourth single from Swift’s 1989 album a chart-topper. Swift’s critics accuse her, generally unfairly, of being a prefab, premeditated commodity. I am usually among those defending her songwriting skill and unwavering fan service. But “Bad Blood”—among the weakest tracks on Swift’s latest album, now a smash—makes that defense harder. It gives ammo to Swift’s haters, which is ironic, since the song, even more than last fall’s “Shake It Off,” is all about defying haters.

Or at least, one hater in particular: “Bad Blood” is a poison letter to Swift’s fellow pop dominator Katy Perry, according to pretty much everyone (including Perry herself). In an interview Swift gave Rolling Stone late last summer in the run-up to 1989’s release, she explained, under tissue-thin cover, that the song was inspired by a fellow award-show-attending pop star and frenemy who, in the end, “tried to sabotage an entire arena tour.” Translation, as revealed by the press: Back in 2013, Perry lured a small troupe of Swift’s backup dancers over to her tour. For Swift, that was the last straw.

This teapot-tempest led Swift—collaborating with her Swedish producer-songwriter BFFs, Max Martin and Shellback—to compose this schoolyard taunt of a song, its nagging two-note hook a musical homage to that playground classic “Nyah, nyah” (“Baaaaaaad blood … Maaaaaaad love … Prooooooo-blems …,” etc.). To Swift’s credit, both the melody and lyric of “Bad Blood” certainly are direct. Like any proficient pop song, it’s relatable and broadly applicable to a range of commonplace contretemps, from a stolen paramour to a fight over the office fridge: “Band-Aids don’t fix bullet holes/ You say ‘sorry’ just for show.” (Hey, Taylor—they’re backup dancers!) On the whole, though, little of Swift’s trademark wit and spiky eloquence—recall the clever way she sent up the tabloids’ image of her on “Blank Space”—wound up in the finished product.

That said, the version of “Bad Blood” that’s atop the Hot 100 is an improvement on the track that debuted on Swift’s 1989 album seven months ago. That’s thanks largely to two people, including one less-heralded artist who’s the remix’s MVP. That guy is 28-year-old producer-songwriter Ilya Salmanzadeh, who reimagined “Blood” for single release. Yes, another Swede—Ilya, as he’s known professionally, is one of his countryman Max Martin’s newest protégés (they collaborated on Ariana Grande’s “Problem” and Jessie J’s “Bang Bang” last year). For the rebooted “Blood,” Ilya has deepened the track’s bass thump, amplified its DJ Mustard–like “HEY!” and pared away most of Taylor’s verses, reducing the song to its refrain plus just a handful of musical highlights. Producer-remixers can have a huge impact on late-breaking album cuts, and if Ilya isn’t quite at the level of a Nile Rodgers or a team like Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, his mix was vital to making the song radio-ready.

But then, of course, the other key player on the “Bad Blood” remix is Kendrick. Long before they collaborated, Kendrick Lamar and Taylor Swift were vocal admirers of each other’s work. Swift was such a superfan of the rapping on Lamar’s now-immortal 2012 album Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City that, on the day she found out 1989 had broken debut-week sales records, she dropped a triumphal, endlessly rewatchable Instagram video of herself lip-dubbing the rapper’s “Backseat Freestyle.” For his part, Lamar has outed himself as a fan of Swift’s prior anti-hater anthem “Shake It Off.” So an actual recorded collaboration between K-Dot and T-Swizzle was probably inevitable.

Lest anyone doubt Kendrick’s appreciation for Taylor, in the second of his two verses on “Bad Blood” he drops a reference to “Backseat Freestyle.” It’s one of many examples of Kendrick’s tongue-tripping turns of phrase on this single; I particularly admire his pileup of percussive plosives on “It was my season for battle wounds, battle scars/ Body bumped, bruised …” But your regard for Kendrick’s performance is directly proportional to your expectations of him at this dizzying moment in his career as rap’s leading light. This is Kendrick in accessible, maximum-pop mode, doing for Swift here what Rakim did for Jody Watley’s “Friends” in 1989 (regarded as the template for the pop song–plus–rap bridge we now take for granted on Top 40 radio). Kendrick’s more than fine on “Bad Blood,” but many of us hold him to a higher standard now.

Besides, Kendrick didn’t really have to bring his A-game to “Blood” to make it a No. 1 hit (his first ever on the Hot 100, for the record). All he had to do was show up.

For decades, labels have used new singles to entice fans to buy greatest-hits albums containing songs they already own. (This is why Earth Wind & Fire came to record their classic “September” for a 1978 hits album, and why Daryl Hall and John Oates recorded two new hits for the 1983 compilation Rock ’N Soul Part 1.) In the age of the digital download, this milk-the-fans tactic has spread to the level of the single. The invention of iTunes more than a decade ago messed with the music industry’s old system for generating hits—in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, albums would go many singles deep. When the labels controlled when each single would be issued at retail, it was possible for, say, the fourth single from Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (“You Make Loving Fun,” No. 9, 1977), the fifth single from Madonna’s True Blue (“La Isla Bonita,” No. 4, 1987), or the seventh single from Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation (“Love Will Never Do (Without You),” No. 1, 1991) to chart high. Now—in an age when all the tracks on an album are available for a la carte purchase from the jump—labels releasing a late single from an album need to give fans a powerful new incentive to purchase a song that’s already been on-sale for months.

This is where Kendrick comes in: A remix of an old single entices both the new, one-off fan and the completist Taylor über-fan to click “buy.” In fact, Swift’s bête noire Katy Perry used the tactic twice successfully in 2011—the fourth No. 1 single from her Teenage Dream album, “E.T.,” was fueled by a Kanye West remix; and the fifth, “Last Friday Night (T.G.I.F.),” was nudged to the top by a Missy Elliott remix. In all these cases, the remixes are the pop-music equivalent of the Star Wars Special Edition cycling through theaters, DVD, Blu-Ray, and streaming video—opportunities to make fans open up their wallets all over again.

Speaking of effects-heavy productions, let’s talk about that “Bad Blood” music video. Swift and her team not only spent major coin to make sure its CGI was state-of-the-art, she also packed the video with a dozen and a half celebrity guests, including so many supermodels you’d be forgiven for thinking the clip is a quarter-century-later sequel to George Michael’s “Freedom ’90.” The cast—each with a fantasy superhero name—is headed by an array of such real-life Friends Of Taylor as Lena Dunham, Ellie Goulding, Hayley Williams, and (in the role of the Katy Perry–manqué villain) longtime bestie Selena Gomez. It’s an impressive four-minute vision of female badassery that goes some distance toward making the sneering “Bad Blood” a would-be feminist manifesto à la Mad Max: Fury Road.

That wasn’t the only way the “Bad Blood” video paid off: On its debut, it set a one-day Vevo record of more than 20 million views. Those video views, coupled with nearly 400,000 in digital sales of the single, the vast majority of them for the Kendrick remix, combined to pole-vault the song to No. 1. With the song also rising at radio, it’s now got an early lead for the Song of the Summer.

If there’s one achievement that’s a reach for Swift now, it’s the all-time record for most No. 1 singles from an album. That number is five, currently held in a tie by Michael Jackson’s Bad (1987–88) and Katy Perry’s Teenage Dream (2010–11). “Bad Blood” is the third No. 1 from 1989 and the fourth officially promoted single, following last fall’s “Shake It Off” (No. 1), winter’s “Blank Space” (No. 1), and early spring’s “Style,” which, despite being one of the album’s best tracks, stalled at No. 6. Naturally, given the ongoing dominance of 1989’s singles, chart-watchers have begun to speculate about whether Swift stands a chance at tying or beating this record.

At the risk of underestimating the reigning Queen of Pop, I suspect she’ll come up short. Tracks like the ’80s-tastic “New Romantics” or “All You Had to Do Was Stay” may have a tough time topping the chart even with a remix, and the underperformance by “Style” reminds us Swift is still mortal. (Both Jackson and Perry scored their five No. 1s consecutively.) Of course, given that the chart record is co-owned by her personal pop nemesis, I wouldn’t put it past Swift to try any tactic—guest rappers, slick videos, TV stunts, you name it—to give Perry a scare. In the pop wars, as in Hollywood sequels, no expense is spared to extend the franchise.

Previously from Why Is This Song No. 1?: