I’ve written quite a bit over the past few years about the death spiral of sea ice at the North Pole. Every year the amount of ice goes up and down with the seasons, growing in winter and declining in summer. But, on top of that there has been a trend downward, such that year by year we see less ice all the time.

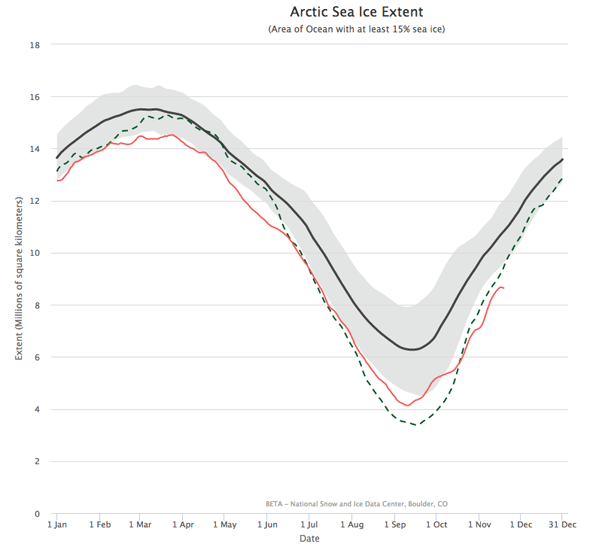

Because of that we tend to see records set nearly every year. For example, this year in March the Arctic sea ice reached its maximum extent,* but it was the lowest maximum extent ever seen since satellite records began in 1979.

Starting in September every year the ice begins to reform, growing to a maximum. It reached that point on Sept. 10 this year, when it had the second lowest extent on record. After that day, though, it started to grow again.

NSIDC

Except … it didn’t. It started to, but then in early October the growth just stopped. A couple of weeks later it started to rise again, but stalled a second time in late October. In the weeks since then the amount of ice has actually fallen a bit. We are now at record low ice for this time of year, and have been for weeks.

Mind you, it’s winter up there. The Sun shines at most a few hours a day at the southern edge of the Arctic Circle right now. Yet temperatures in the Arctic are soaring; in mid-November it was an average of a staggering 22° Celsius, or 40° Fahrenheit, above normal.

Holy cripes. What the hell is going on?

The obvious answer is: global warming. Like I said, as time goes on, average temperatures go up, and amount of ice decreases.

But there’s a less obvious but more important answer, too. And that is: global warming.

That’s not a typo. The proximate cause of the temperature spike has been a weak jet stream. That blows around the pole, and generally keeps the cold air up there and the warm from the south away. But the jet steam has been weak lately, and warm air has been able to push up into the Arctic and keep temperatures up.

So why is the jet stream weak? Yup. It’s global warming. One thing that powers the jet stream is the difference in temperature between mid-latitudes and the more northern ones. As the planet warms, that difference has fallen (the Arctic warms faster than lower latitudes do), and that has weakened the jet stream.

But there’s more. Because the planet is warming, the sea surface temperatures are going up as well. Water that’s usually frigid in October (like the East Siberian and Barents Seas) has been warmer, so ice growth is slow.

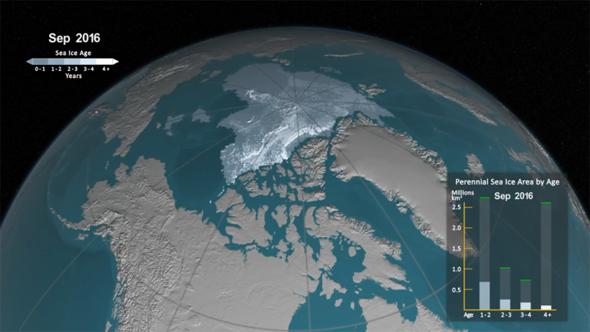

There’s a subtle thing happening here too that’s important. It’s not just that we’re seeing slower ice growth, but the high temperatures are actually melting old, thick ice as well. So it’s not just the extent that’s dropping, it’s the volume as well. That’s important because thin ice comes and goes, melting faster in the summer, but the old thick ice should be here to stay. That’s no longer the case; we’re losing that too.

Here are two videos showing that. The first, from NASA, shows a map of Arctic ice over the years:

The second, by Andy Lee Robinson, shows this even more clearly using a graphical approach:

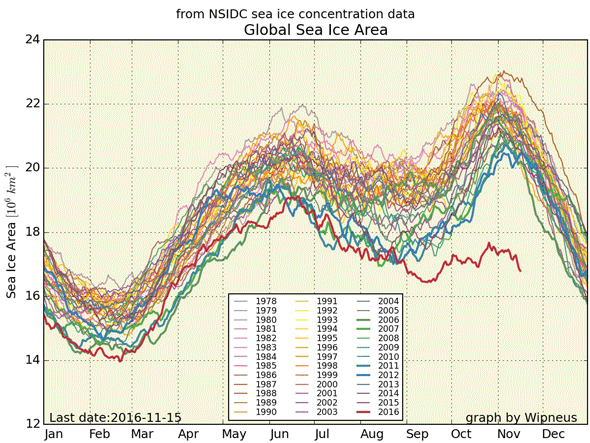

I have to add that another graph has been making the rounds, showing the total global sea ice extent. It’s troubling as well, but it comes with a caveat. Here’s the graph:

Zack Labe/Wipneus

This follows the amount of sea ice at both poles, Arctic and Antarctic. It’s not really a good way to understand what’s happening because the physical conditions at the two poles are very different, and the amount of ice at each is ruled by different circumstances. Combining them just confounds all this.

Right now it’s approaching summer in the Southern Hemisphere, and we expect Antarctic ice to decline. However, even so, it’s falling faster than usual, and the extent there is lower than normal, too.

I include this graph because so many people are talking about it, and it’s important to understand that scientists don’t usually combine the two poles into one graph that way.

However there’s a second point to make as well. Whenever I write about Arctic ice, a herd of climate change deniers converge in the comments and on social media, barking about how Antarctic sea ice is unchanged or even on the rise. But—shocker—that’s crap. The two are unrelated; Antarctic sea ice tends to be relatively steady year to year, and, as you can see, despite that it is pretty low right now.

And they also ignore the fact that Arctic ice has been steadily decreasing for decades. Well, steadily until the past few weeks.

It’s possible that the boreal ice will get its act together and start growing again this season. It’s also possible it won’t. Time will tell.

But time is not on our side. It’s entirely possible we’ll see our first ice-free Arctic summer in just a few decades. Not centuries, or even a century. But maybe by 2040.

The reason this is a concern is twofold. One is that as the northern ice melts, it dumps a lot of fresh water into the oceans. This changes the salinity of the oceans, and that changes how the water flows from the Arctic to the equator and back again. This heat exchange powers a lot of our climate and weather, so having this break down is, in a word, terrifying.

Second, the Arctic is our climate canary-in-a-coal-mine. Because it’s so sensitive to warming, studying it shows us what we’re in for as our planet inexorably heats up.

I won’t spin this: This is not good news. As I wrote recently, all is not lost, and there are still things we can do to help mitigate global warming.

But with Donald Trump in office, and him loading his Cabinet with climate change deniers, I worry very much over what the next few years will entail.

*Extent is a term climate scientists use, and it’s a little different than just the area of the ice. When they measure the ice they divide the area into regions, and if a region is more than 15 percent ice they say it’s ice-covered.