In November 1834, a 9-year-old boy named Major Mitchell was tried in Maine on one charge of maiming and one charge of felonious assault with intent to maim. He had lured an 8-year-old classmate into a field, beaten him with sticks, attempted to drown him in a stream, and castrated him with a piece of tin. Yet what makes this case so remarkable is neither the age of the defendant nor the violence of his crime, but the nature of his trial. Mitchell’s case marks the first time in U.S. history that a defendant’s attorney sought leniency from a jury on account of there being something wrong with the defendant’s brain.

More recently, there has been an explosion in the number of criminals who have sought leniency on similar grounds. While the evidence presented by Mitchell’s defense was long ago debunked as pseudoscience (and was rightly dismissed by the judge), the case for exculpating Major Mitchell may actually be stronger today than it was 181 years ago. In a curious historical coincidence, recent advances in neuroscience suggest that there really might have been something wrong with Major Mitchell’s brain and that neurological deficits really could have contributed to his violent behavior.

The case provides a unique window through which to view the relationship between 19th-century phrenology—the pseudoscientific study of the skull as an index of mental faculties—and 21st-century neuroscience. As you might expect, there is a world of difference between the two, but maintaining that difference depends crucially on the responsible use of neuroscience. Major Mitchell’s story cautions against overlooking neuroscience’s limitations, as well as its ability to be exploited for suspect purposes.

According to Major Mitchell’s defense, the boy “had received an injury of the head, in the consequence of a fall while quite young, whereby the portion of the brain called, by Phrenologists, the organ of Destructiveness, was preternaturally enlarged and a destructive disposition excited.” In other words, a blow to the head had left him with a permanent bump behind his right ear, supposed evidence of a permanently swollen appetite for destruction. Since a child is not responsible for falling on his head, the defense argued, neither is that child responsible for the consequences of falling on his head. And if Major Mitchell’s assault on his classmate resulted from earlier damage to his “organ of Destructiveness,” then he could not be held legally responsible for that assault.

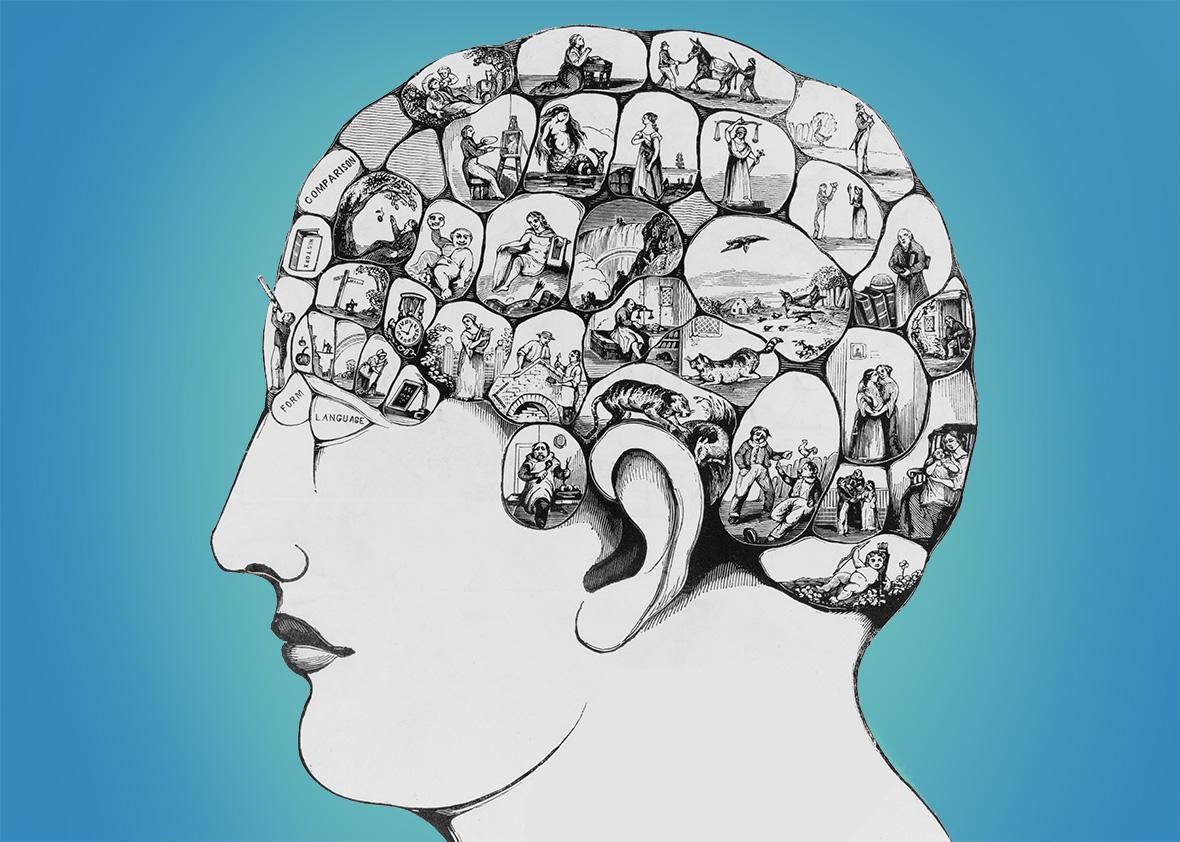

At the time, phrenology was just beginning to garner the veneer of legitimacy. In 1837, the prestigious medical journal the Lancet had published an 18-lecture course on the so-called science of phrenology. Phrenologists believed that different mental faculties were located in distinct organs in the brain and that, like muscles, these organs grew or shrank depending on their strength. In theory, measuring the size, shape, and features of someone’s skull could reveal important facts about a person’s various psychological traits. In practice, these pseudoscientific observations mostly served as a way to reinforce pre-existing stereotypes about the inferiority of women and non-Caucasians.

Mitchell’s judge was not impressed, and he ordered that all phrenological testimony be thrown out. “Where people do not speak from knowledge,” the judge opined, “we cannot suffer a mere theory to go as evidence to a jury.” The boy, though only 9 years old, was found guilty on both counts and sentenced to nine years of hard labor in state prison.

Initially, proponents of phrenology had hoped the trial would serve as “an augury for its future stupendous influence.” They were disappointed by its outcome, admitting that they “could have wished a better case for the introduction of the light of Phrenology, into the dark passages of our Criminal Law.” But in retrospect, the judge’s opinion seems prescient—phrenology has long since been discredited. By 1845, Adam Sedgwick, one of the founders of modern geology and a mentor to the young Charles Darwin, referred to phrenology as “that sinkhole of human folly.”

But uncertain behavioral and brain science continue to appear in—and usually be tossed out of—the courtroom. According to Nita Farahany, a law professor at Duke University and member of the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, neuroscience or behavioral genetics appeared in more than 1,800 judicial opinions between 2005 and 2012 but was viewed favorably in only about 20 percent of those cases. Neuroscience has many legitimate uses that can be relevant to trials, such as detecting brain diseases that impair normal functioning and contribute to illegal behavior, but in many cases, its use is spurious.

Just this year, a defense team in New Mexico argued that its client’s sentence should be reduced because he had a neurogenetic predisposition to violent behavior. That client had beaten an elderly man to death, doused the body in cooking oil, and set it on fire. The judge was not moved by the genetic evidence.

Even though judges tend to be skeptical of shaky neuroscience, it can still have a substantial influence on the legal process. Most people are susceptible to a sort of “seductive allure of neuroscience explanations,” and the fear of a jury’s response to colorful brain scans can motivate lawyers to settle cases out of court. This may be how things went for one lucky plaintiff, who in 2006 hired a Columbia University professor to provide supposedly objective functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, evidence of chronic pain. After the judge admitted those images into the trial, the plaintiff was able to leverage an $800,000 out-of-court settlement from his employer for a work-related injury. There is no way to know whether the admission of the scans influenced the defense’s settlement, but it certainly could have.

Brain scans were first used in the U.S. courts in 1982 in defense of John Hinckley Jr., the man who attempted to assassinate President Reagan. Hinckley was diagnosed with schizophrenia partly on the basis of computer-assisted tomograph and was ultimately found not guilty by reason of insanity. Ten years later, fMRI made its U.S. courtroom debut, revealing that a New York man charged with homicide had an arachnoid cyst pressing down on his brain. As a result, his sentence was reduced from murder to manslaughter.

Other criminal defendants have also benefited from fMRI. These defendants include one man whose sudden, uncontrollable interest in child pornography twice disappeared after a recurring brain tumor was detected and removed. The tumor had been pressing on his orbitofrontal cortex, a region that over the past 15 years neuroscientists have repeatedly found to be involved in social decision-making and, in some laboratory experiments, moral decision-making.

Regardless of how appropriate or inappropriate forensic fMRI may be in certain cases, it seems poised to become big business. Recognizing a financial opportunity, companies like Millennium Magnetic Technologies have sprung up, which for a fee claim to provide fMRI evidence of chronic pain for injury lawsuits. Other companies, like Cephos LLC and No Lie MRI, market fMRI lie detection to clients seeking to prove their innocence. Although the scientific basis for these companies’ claims is flimsy, the services typically charge between $4,500 and $6,000 for brain scans. While both companies have so far been unsuccessful in their attempts to have fMRI lie detection admitted into evidence at trial, there is no way to know how many out-of-court settlements or extralegal disputes they may have affected.

Illustration from Annals of Phrenology, Volume 2, by Nahum Capen via Google Books

Oddly enough, there are reasons to think that Major Mitchell’s fall as an infant really could have influenced his behavior as a 9-year-old. We now know that traumatic brain injury during childhood is associated with an increased risk of psychopathology and violent criminality. In fact, a study that followed 12,000 Finnish children for 35 years found that people diagnosed with TBI prior to the study’s commencement in 1966 were four times more likely than others to be convicted of crimes and to have mental disorders in adulthood.

Even more striking is the recent discovery that the exact brain region Major Mitchell seems to have injured has recently been linked to immorality. The right temporo-parietal junction, or rTPJ—a brain area behind the right ear, where Major Mitchell’s permanent bump was—is now thought by neuroscientists to be involved in “theory of mind.” Theory of mind refers to the ability to perceive the mental and emotional states of others, and it is crucial for healthy socialization. It may also be essential for maintaining ethical behavior, since perceiving both the intentions and the potential suffering of others plays an important role in moral judgment and inhibition.

Recently, researchers at MIT conducted an experiment in which they interfered with participants’ rTPJs using magnetic stimulation. They then asked those participants to judge the moral permissibility of acts in which one person harmed another. Participants whose rTPJ function had been disrupted were less likely to rely on others’ mental states when making moral judgments, and tended to find harms more morally acceptable and less forbidden than other participants did. In a separate experiment using fMRI, the researchers also found that the rTPJ was especially active during certain kinds of moral judgments.

The phrenologist who testified on Major Mitchell’s behalf certainly didn’t know something that neuroscientists are only now beginning to recognize. The history of science is filled not only with impressive predictions but also with striking coincidences, and this is a case study in the latter. Just as Kepler happened to guess correctly that Mars had two moons (after erroneously trying to decrypt an anagram Galileo had sent him about the rings of Saturn), the first argument drawing on “brain science” in the courtroom happened to bear a close resemblance to something that might be admissible in court today. Still, the story can help us understand the value and sophistication of contemporary neuroscience.

Unlike phrenologists, today’s researchers are under no illusion that they have once and for all found the moral center of the brain. Instead, they are beginning to grasp just how multifaceted moral decision-making and behavior really is. The rTPJ is involved in theory of mind, sympathy, and attention to social cues, among other things. These functions, and therefore the neural circuitry of the rTPJ, are only a few among many factors that contribute to and, ultimately, facilitate moral cognition.

Perhaps Major Mitchell’s fall did contribute in some way to his violent behavior. But if it did, it would not have done so by increasing his appetite for destruction. It would only have done so by reducing his attention to and sympathy for others’ suffering. It likely would not have created new urges to be violent; it would only have eliminated some of the natural mechanisms humans have to inhibit our violent urges. Neuroscientists now understand that an “organ of Destructiveness” is a misguided idea not just because there is no destructiveness organ in the brain but because there are no specialized organs in the brain at all.

The smallest unit that many neuroscientists now see as a valid construct is the entire nervous system—not just the brain, let alone one of its isolated parts. This is the biggest difference between the phrenology of the 19th century and the neuroscience of today. The very idea of modularity—of separate little brain regions at work on separate little problems—is no longer supported. And our ability to outgrow that idea has made the conceptual system provided to us by neuroscience that much more complex. It has also made our decisions regarding how to understand, treat, and punish criminals whose brains may be damaged or abnormal that much more complicated.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.