A great story changes with the times. Decades after it’s published, a narrative with depth and dimension will still give up secrets, signifying different things to each generation. But this feat is particularly tricky in the horror genre, since society’s fears—the fuel in any good horror story—can change significantly over time. A story that can still terrify readers 90 years after it’s published is a rare thing.

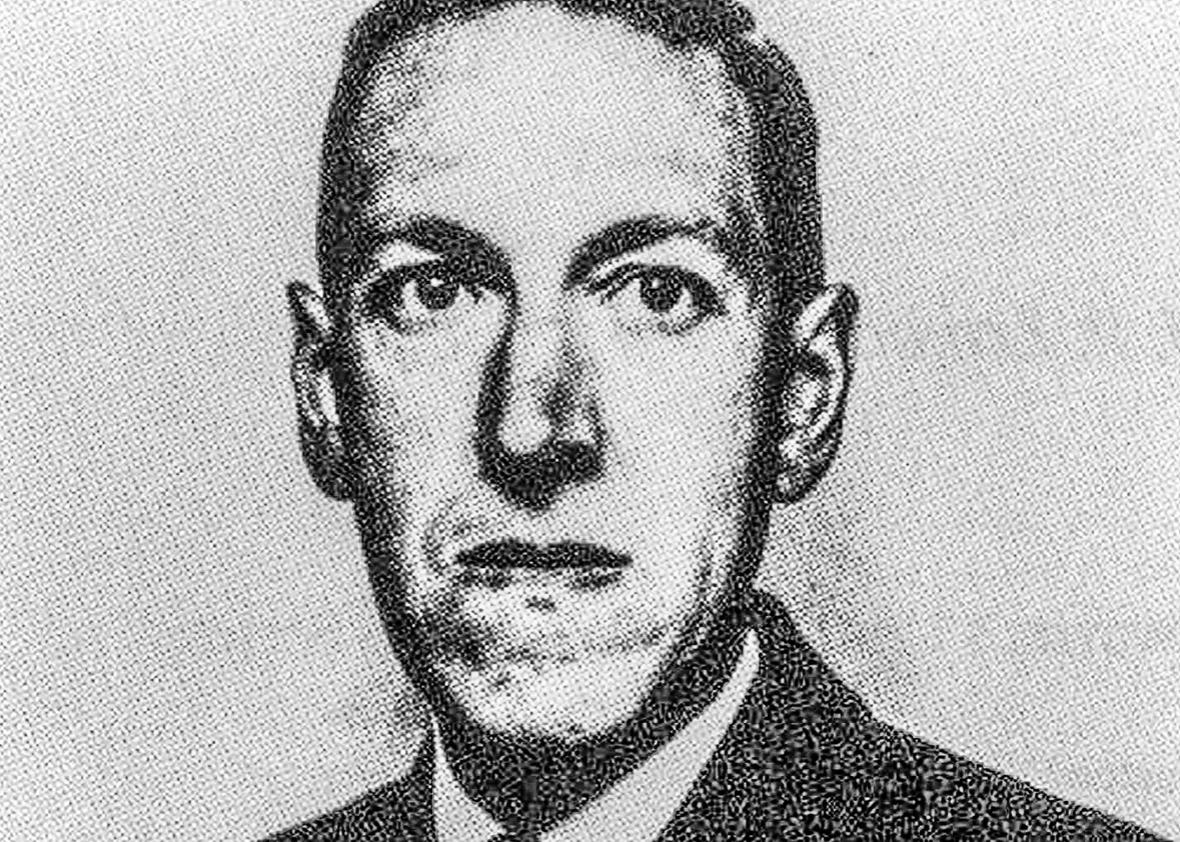

H.P. Lovecraft, master of the weird tale, has taken some hits recently. Greater awareness about his racism has triggered a re-evaluation of his work, including a call to remove his image from the World Fantasy Award. These (important) cultural conversations are emblematic of a fundamental problem: Lovecraft’s work hasn’t aged well, and as a result, some stories aren’t as scary as they used to be.

Effective horror stories present a stand-in for people’s anxieties. (For example, it’s not the ghosts that frighten us in The Shining—it’s Jack’s alcoholism.) In Lovecraft’s work, the underlying anxieties are often racial. For instance, in his most famous story, “The Call of Cthulhu,” a worldwide cult consisting of “diabolist Eskimos,” South Asians, and Louisiana voodooists attempt to raise Cthulhu, an apocalyptic alien god living in stasis under the Pacific Ocean. Multiple Lovecraft stories deal with race mixing. Taken as a whole, his stories seem to postulate that anyone who isn’t white or upper-class is secretly colluding to end the world. These elements are undeniably offensive to modern readers, but this racial dimension, originally intended to enhance the horror, also doesn’t scare us like it used to. Cultural progress has reduced (though by no means eliminated) American anxieties about race, blunting these stories. Like the 1950s tales of nuclear mutants, they no longer speak to modern fears.

But not all Lovecraft stories are getting less frightening. While one Lovecraftian theme loses its edge, another—the tainted landscape—is more relevant than ever. Because here’s what our society is scared of: being poisoned.

I don’t mean in the Agatha Christie, this-tea-smells-like-almonds sense; I mean in the asbestos sense. We worry that our society is full of toxic materials that corrupt our bodies and our planet. Articles warn us away from pesticides in our food, baby products made overseas, and anything dyed with Yellow No. 5. Air purifiers fly off the shelves in China, and Americans show increasing concern about contaminated groundwater. We worry everything we touch, eat, and breathe is killing us—and Lovecraft is right there with us.

In Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space,” a meteor lands on a farm in rural Massachusetts, not far from the university town of Arkham. Puzzled by the meteor’s strange properties, the Gardiner family invites scientists to examine the object, which emits an unknown spectrum of ultraviolet color. Soon, local farmers realize something not quite right is happening at the Gardener place. The well water tastes foul. Fruits and vegetables grow in fantastic colors, and animals exhibit strange behavior. Before long, the vegetation turns gray and brittle, and the bodies of their livestock start to crumble and cave in. At night, the farm glows with an indescribable color. A neighbor warns the Gardeners not to drink from their contaminated well, but the family—already going mad from the noxious water—doesn’t listen. The Colour, a sort of vampiristic pollutant from the stars, eventually leaves Earth after eating its fill. The ashen blight around the farm, however, continues to spread about an inch a year. In the end, the narrator reveals that the state intends to flood the valley and use it as a reservoir for the nearby city of Arkham.

“I hope the water will always be very deep,” he concludes. “But even so, I shall never drink it.”

“The Colour Out of Space” is a story with staying power, malleable enough to adapt to changing fears. Though Lovecraft died in 1937, long before mass-pollution became an American concern, the story resonates surprisingly well with 21st-century horrors. Nuclear meltdowns like Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi plant leap to mind when one reads about the glowing trees and mutations at the Gardener farm. Likewise, the most disturbing part of the story—that the family is unable to leave, even when warned—recalls the so-called cancer villages in China, where whole towns live in a carcinogenic environment. “The Colour Out of Space” speaks to our mass-pollution fears—air quality, industrial pollutants, oil spills—the unwholesome elements we breathe or consume, but have little power to change. In “The Colour Out of Space,” as in life, once we admit there’s a problem it’s often far too late. By the end of the story, we can only hope the Colour won’t pollute the reservoir.

But if “The Colour Out of Space” is about macro-pollution, Lovecraft’s The Shunned House zeroes in on the micro-pollutants that make an individual property unlivable. In the story, an antiquarian takes interest in the sinister legends surrounding a home in Providence, Rhode Island. The house isn’t so much haunted as it’s unwholesome—for more than a century, anyone living there has weakened and died. It’s as if something, perhaps the unnatural basement mold shaped like a doubled-over body, saps their vitality. Eventually, the house develops a distasteful reputation and sits empty. It’s only after the narrator confronts a sickly vaporous entity, and fumigates the basement with chemicals, that the property becomes safe for habitation.

The Shunned House is one of Lovecraft’s most frightening tales. While other works contain more sweeping or original visions, there’s something disturbingly credible about a house that sickens tenants. What’s particularly chilling is that it kills gradually—so gradually the pattern’s only detectable with decades of hindsight.

Lovecraft deepens the dread with descriptions familiar to anyone who’s lived in a house past its prime. His treatment of the humid cellar, full of unexplained vapors and “white fungous growths,” cues immediate recognition and revulsion.

I’ve been in places like that cellar, and I bet you have, too. For me, it was a hotel room where the bathroom’s wooden walls were soft and stained black with mildew. My throat could feel spores in the air. Like the characters in The Shunned House, humans instinctively know and fear contaminated dwellings. Asbestos will drive us out of a building. Studies increasingly raise concerns about carbon dioxide building up in homes. Gas stoves feed a constant, low-level anxiety that a leak might suffocate us in our sleep. The fear is familiar, and thus terrifying.

The story even takes a brief detour into social commentary at one point, when the homeowners desert the house and begin renting it to poor families—a situation that really occurs in apartments with black mold.

Despite Lovecraft’s archaic writing style, these stories feel at home in today’s fiction, where eco-horror is the bleeding edge. You can see this environmental anxiety in the mutated landscapes of the Southern Reach Trilogy, the resource scarcity of Stephen King’s Under the Dome, and carcinogenic wastes of Mad Max: Fury Road. Climate change is sci-fi’s new nuclear war, the overriding force that creates monsters or turns us against one another.

Any horror writer can frighten readers, but only a master can frighten his original readers’ great-grandchildren. What other modern fears will make us reinterpret Lovecraft’s work? Will our social media-steeped society, where stolen identities are just a copied profile picture away, identify with Charles Dexter Ward? Perhaps climate change will strengthen At the Mountains of Madness, which ends with scientists begging their colleagues not to drill or melt Antarctic glaciers.

In the future, when the sea rises, will we think of Cthulhu emerging from the deep as we watch our cities drown?

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.