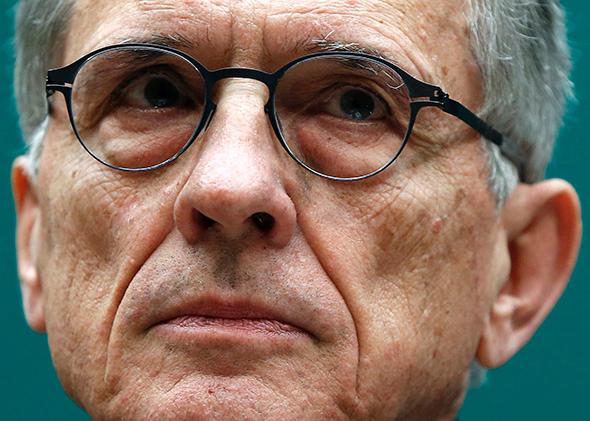

The Wall Street Journal and New York Times have reported that controversial FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler is floating a “trial balloon” for its net neutrality rule. If the reports are accurate, the proposal would ignore 3.7 million comments that almost unanimously urge the FCC to ban fast and slow lanes and to adopt straightforward, solid legal authority—after losing twice in court for lack of authority. In addition to ignoring the public, it would also ignore dozens of senators and members of Congress in Wheeler’s own party, not to mention the president who appointed him.

The rule—which will likely be adopted Dec. 11, with an internal draft circulated by Nov. 20—would permit fast and slow lanes on the Internet, in part because it rests on a new and exotic theory of legal authority that will almost certainly fail in court, for the third time —even though judges and members of Congress keep pointing to an obvious, strong authority at the heart of communications law.

While the actual proposal is not available to the public, the reports appear in line with what the FCC is telling stakeholders. Based on those reports, there are two major problems here—the rules and the authority they rest on. Both are important. In 2010 we were told to focus on the rules and ignore the authority, and that’s exactly why the FCC lost in court.

Problem 1: Fast Lanes and Slow Lanes

Data can generally travel the speed of light unless networks are congested. When there’s congestion, usually the cheapest and best thing is simply to add capacity generally, not to prioritize certain sites over others. A rule against paid fast lanes would encourage additional capacity; a rule permitting paid fast lanes would simply encourage cable companies to create congested slow lanes on the Internet so they could make money by selling fast lanes to big companies. The FCC reached the same conclusion in a previous decision under a previous Democratic chairman. (If you’re ambitious, see Page 59,207.)

The current FCC—led by a controversial and embattled chairman who was once a top cable lobbyist—instead wants to permit fast lanes in some circumstances, and at most will adopt a “rebuttable presumption” against paid prioritization, likely with a vague “case-by-case approach.”

Here’s how it would work. If you file a complaint and prove that Verizon or Comcast is offering fast lanes, then the FCC will presume the fast lanes are “unreasonable” or “harmful.” But this presumption is “rebuttable,” meaning that Verizon or Comcast will then have the opportunity to prove that its fast lane is actually good for consumers. This rebuttable presumption is what cable and phone companies such as Verizon and Comcast have been asking for. Unless the FCC set out a very strict set of clear factors that need to be proved, it would not provide nearly the level of certainty needed to protect large Web companies, let alone startups, nonprofits, and average Americans.

Imagine that you run a startup or nonprofit that has filed a complaint. AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast can spend millions on lawyers and economists, trying to rebut presumptions and arguing that each fast-lane deal is a good thing. You’d have to hire your own guns to respond to each rebuttal, in a long war of attrition. That’s why a long list of companies and groups are calling for bright-line rules instead of this vague “case-by-case” business: the Internet Association (which is made up of the largest tech companies), Tumblr, Vimeo, Sidecar, Reddit, and Imgur. They’re all calling for something similar: a rule against tolls to reach users and against discriminating based on content or application. That’s a readily enforceable standard and would provide certainty to the economy.

Problem 2: The FCC Will Lose in Court

The proposal is deeply confusing, but here’s the gist. It would break up Internet access into two separate services offered by cable and phone companies—one service is offered to average users, and simultaneously a second service is offered to every website on the Internet so that it can reach those users. So Comcast offers me one service, governed by a part of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 now referred to simply as Section 706, and that service gets me to the Internet. At the same time, it also offers Tumblr a telecommunications service, governed by Title II of the Communications Act. The service offered to Tumblr is essentially the “service” of not being blocked by Comcast and to be carried all the way to me. While this might be hard to wrap your head around, these services are completely overlapping at all points because Comcast (or Verizon) is providing me a service by carrying Tumblr sites to my computer and providing Tumblr a service of not blocking them when I request those sites.

To be clear, the FCC has never before broken up any service in this way. Usually Title II applies to services where a phone or cable company offers to connect users to other users—right now this includes Internet access services offered to businesses, Internet access in many rural areas, and also long-distance and mobile phone calls.

This two-service approach will never hold up in court because, among other reasons:

- It’s totally new and extremely hard for people to explain and understand. Judges do not usually embrace exotic legal theories coming from federal agencies.

- A Title II service actually has to meet a definition set out by Congress. The definition requires the service to be “offered” “directly” “for a fee.” But Mozilla, Vimeo, and Tumblr do not pay every consumer ISP in the United States (or the world) fees to reach their consumers.

- The service may not even be “directly” offered since it’s a magical service offered from Comcast to all websites it is not blocking.

The FCC should obviously not propose bad rules that will be struck down; it should propose good rules that will be upheld.

So far, people are still trying to dig through exactly what Wheeler is trialing. But the tl;dr is the FCC is still barreling toward rules that will permit paid prioritization and get struck down in court—and that could cause lasting harm to the open Internet that has transformed our lives and our economy.

Disclosure: The author is a lawyer who has advised startups and nonprofits on net neutrality issues, but these views should not be attributed to them.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.