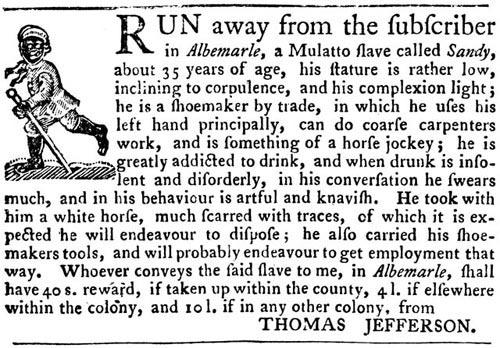

In the fall of 1769, Thomas Jefferson lost a slave. His name was Sandy, and he was a runaway. Sandy was “about 35 years of age.” He worked as a shoemaker. Jefferson described him as “artful and knavish.” He was also “something of a horse jockey.”

Jefferson criticized slavery. Yet when he signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, Jefferson owned almost 200 human beings. When Sandy went missing, he owned about 20; losing even one was significant. So Jefferson used the best available technology to find Sandy: the newspaper ad.

Sandy was caught and later sold for 100 pounds. Around the turn of the century, however, things slowly started to change. A secret network was built to help people like Sandy. Over time, tens of thousands of runaway slaves would escape bondage on the Underground Railroad.

How many of them would have made it in the age of big data?

There is a booming debate around what big data means for vulnerable communities. Industry groups argue, in good faith, that it will be a tool for empowering the disadvantaged. Others are skeptical. Algorithms have learned that workers with longer commutes quit their jobs sooner. Is it fair to turn away job applicants with long commutes if that disproportionately hurts blacks and Latinos? Is it legal for a company to assign you a credit score based on the creditworthiness of your neighbors? Are big data algorithms as neutral and accurate as they seem—and if they’re not, are our discrimination laws up to the challenge?

These questions need answers. Most of the questions, however, focus on how our data should be used. There’s been far less attention to a growing effort to change how our data is collected.

For years, efforts to protect privacy have focused on giving people the ability to choose what data is collected about them. Now, industry—with the support of some leaders in government—wants to shift that focus. Businesses say that in our data-saturated world, giving consumers meaningful control over data collection is next to impossible. They argue that we should ramp down efforts to give individuals control over the initial collection of their data, and instead let industry collect as much personal information as possible.

Privacy protections? They would come after the fact, through “use restrictions” that would prohibit certain uses of data that society deemed harmful. We used to try to protect people at each stage of data processing—collection, analysis, sharing. Now, it’s collect first and ask questions later.

This isn’t a fringe argument. It was endorsed by the World Economic Forum of Davos as well as the president’s own Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, which issued a report on the subject in May. “The beneficial uses of near-ubiquitous data collection are large, and they fuel an increasingly important set of economic activities,” the president’s council wrote. “[A] policy focus on limiting data collection will not be a broadly applicable or scalable strategy—nor one likely to achieve the right balance between beneficial results and unintended negative consequences (such as inhibiting economic growth).”

As Chris Jay Hoofnagle wisely explains in Slate, industry’s noisy embrace of ubiquitous collection is really an attempt to deregulate data privacy. Unfortunately, deregulation will hurt some much more than others.

Davos and the president’s council are basically saying that it’s OK to vacuum up data, so long as you prohibit certain harmful uses of it. The problem is that harmful uses of data are often recognized as such only long after the fact. Our society has been especially slow to condemn uses of data that hurt racial and ethnic minorities, the LGBT community, and other “undesirables.”

In the spring of 1940, Japanese Americans received visits from census examiners. With war burning across Europe and Asia—and with a growing alliance between Japan and Germany—these visits could not have been comfortable. Yet by and large, Japanese-Americans cooperated with the census. After all, by federal law, census data was subject to strict use restrictions: The Census Bureau was required to keep personal information confidential.

Their trust was misplaced. In 1942, Congress lifted the confidentiality provisions of the census, letting the Census Bureau share detailed data with other government agencies “for use in connection with the conduct of the war.” The War Department would go on to use detailed census data to track Japanese Americans and round them up for internment camps.

In the years after the war, a similar story unfolded for gay and lesbian soldiers. Banned from serving openly, many LGBT service members turned to military chaplains, physicians, and psychologists for emotional and medical support. These counselors were the only people the service members thought they could trust. This frequently proved to be a serious mistake. From the 1970s to long after “don’t ask, don’t tell,” military chaplains, physicians, and psychologists used confidentially collected information to “out” gay and lesbian service members to their superiors.

Photo by Dorothea Lange/Getty Images

These incidents now strike us as repugnant discrimination. At the time, the picture was less clear for many. It took the Census Bureau 65 years to acknowledge the full extent of wartime sharing of Japanese Americans’ data. And Congress repealed the military’s ban on openly serving gay and lesbian soldiers only in 2010. That was one year after the president announced an end to HIV/AIDS tests for new immigrants, and the use of that data to deny green cards to those who tested positive. The HIV travel ban had been in place for 22 years.

There is a moral lag in the way we treat data. Far too often, today’s discrimination was yesterday’s national security or public health necessity. An approach that advocates ubiquitous data collection and protects privacy solely through post-collection use restrictions doesn’t account for that.

Last year, in the wake of Edward Snowden’s revelations, sociologist Kieran Healy speculated about whether the British crown could have used metadata analysis to find Paul Revere. (Spoiler alert: They find him.) In a world of ubiquitous data collection, what would have happened to American revolutionaries? What would have happened to gay and lesbian soldiers? What would have happened to runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad?

Runaway slaves lived by subterfuge and evasion. They relied on safe houses and coded letters between their hosts. Spirituals—seemingly innocent religious songs—told slaves to “wade in the water.” The imagery was actually advice on how to avoid the bloodhounds that slave catchers would use to track them.

What would have happened if geolocation were effectively a matter of public record? If any company or individual who wanted that data could get it, either from another company or through the use of a Stingray? What if every horse and carriage were monitored through an analog of today’s license plate-tracking systems? The road to freedom would have been much more difficult—particularly after 1850, when the Fugitive Slave Act forced government officials to help private slave catchers.

These examples may seem extreme. But they highlight an important and uncomfortable fact: Throughout our history, the survival of our most vulnerable communities has often turned on their ability to avoid detection.

There was a time when it was essentially illegal to be gay. There was a time when it was legal to own people—and illegal for them to run away. Sometimes, society gets it wrong. And it’s not just nameless bureaucrats; it’s men like Thomas Jefferson. When that happens, strong privacy protections—including collection controls that let people pick who gets their data, and when—allow the persecuted and unpopular to survive.

Privacy is a shield for the weak. The ubiquitous collection of our data—coupled with after-the-fact use restrictions—would take that shield away and replace it with promises.

Let me be clear. The engineers and entrepreneurs behind big data are good, brilliant people. They aim to advance public health, better our businesses, and improve our society. Many of those benefits will accrue to vulnerable communities. Sophisticated data analysis, for example, is critical to identifying and proving discrimination in voting, housing, and education cases. As data sets grow larger and richer, those benefits will grow as well.

The problem is not that the proponents of big data are nefarious—they’re not. The problem is that all of us, as a society, are startlingly bad at protecting the data of vulnerable communities, and recognizing when use of that data crosses a line. And while data collection and analysis bring powerful benefits, those benefits cannot justify the ubiquitous collection of our information, or a broad reduction in our ability to control it. I’m not arguing against all data collection; I’m arguing against collecting all data.

We should welcome the benefits of big data. But we should also remember our history, and ensure that those benefits do not come at the expense of the basic right to be let alone.

Róisín Áine Costello assisted in researching this article.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.