A recent New York Times article reported that up to 18,000 species around the globe are discovered by scientists every year. That flashy number comes from the International Institute for Species Exploration, a taxonomic effort run out of the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry. It’s a rough estimate and probably a generous one, but it’s nevertheless true that scientists document thousands of new species annually—as well as many species thought to be extinct but recently rediscovered.

Newly discovered and rediscovered species are a bright spot in the murky gloom of the extinction crisis. They’re also a reminder of the scrappy resilience of animal and plant life on Earth, even as tropical forests yield to oil palm plantations, the sea and land are stripped of profitable species, and the climate changes.

These scores of discovered and rediscovered species, though, obviously need to be identified and distinguished from animals and plants already catalogued. How is this done? The traditional method is to collect a “voucher” specimen from the field—i.e., taking a bird, fish, frog, insect, plant, etc., back to the lab to describe its taxonomic characters. Typically the specimen is then deposited in a natural history collection, where it’s pinned, pickled, and preserved for later scientific reference and study.

But what if it turns out that the new or rediscovered species exists only in a small and isolated population—that is, one very vulnerable to human impact? Even more likely, what if we just don’t know how many individuals of the species there are in the wild when a specimen is taken?

A recent case from New Guinea provides a good illustration of this challenge. In 2012, Australian researchers working in New Guinea collected dozens of small bats from a handful of known species. Among the specimens taken was a female bat that they could not identify in the field. It was deposited in the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery, where it sat (presumably very quietly) for a couple of years.

This spring an Australian museum researcher requested the specimen and was able to determine that it was, in fact, a New Guinea big-eared bat, a species last observed in the late 19th century and long presumed lost. Despite its happy return from the (apparent) dead, scientists have no idea how many individuals of the species currently exist in the wild.

Cases like the New Guinea big-eared bat reveal a conundrum at the heart of scientific methodology regarding the description of new species or rediscovered species that may exist in small numbers and thus are highly vulnerable to human pressure—including scientific study. The population of the big-eared bat may indeed turn out to be large enough so that collecting one female (or several) doesn’t make the species more vulnerable to extinction. But the point is that we can’t know for sure, and so collecting a specimen in these cases could unintentionally increase the extinction risk to the species. When the population is small and vulnerable enough, every individual matters.

Should, then, scientists take specimens in these cases—when there is uncertainty about population size yet good reason to believe that it may be very small? Should they take this risk?

I don’t think they should. In a recent paper published in Science, I and my co-authors James P. Collins, Karen E. Love, and Robert Puschendorf argue that methodological traditions in field biology and taxonomy encouraging the collection of voucher specimens to confirm a species’ existence can indeed magnify and combine with other forms of extinction risk for small populations of rare and vulnerable species.

Although specimen collection norms are deeply ingrained in many scientific communities, there are now alternative methods of documentation, including high-resolution photography (even with a smartphone), audio recording (if the organism has a call), and noninvasive DNA sampling (for instance, via skin swabbing). The voucher specimen should, we argue, no longer be viewed as the “gold standard” in species description, especially given the power and availability of these alternative technologies and means of description. When used together, these techniques can provide a very effective, nonlethal method for identifying new or rediscovered species.

Our paper has kicked a hornet’s nest. More than 120 academic and museum scientists on six continents apparently took great offense to our proposal, as evidenced by the strongly worded letter they sent to Science (published, with our reply, in the May 23 issue). The authors doubled down on the necessity of the voucher specimen in taxonomic description and vigorously defended natural history museums from what they took to be an anti-scientific assault on their value.

But—and this should be clear from our original paper—the focus of our concern is the special case of collecting specimens from vulnerable populations (especially when we don’t have a reliable estimate of their size). In other words, and despite what our critics suggest, we aren’t advocating the banning of all forms of specimen collection. To say that would have been hypocritical—two of my co-authors (Collins and Puschendorf) have and continue to collect research specimens. And we certainly have no animus toward natural history museums. In fact, we admire them and appreciate the work they do for science and education—and for conservation.

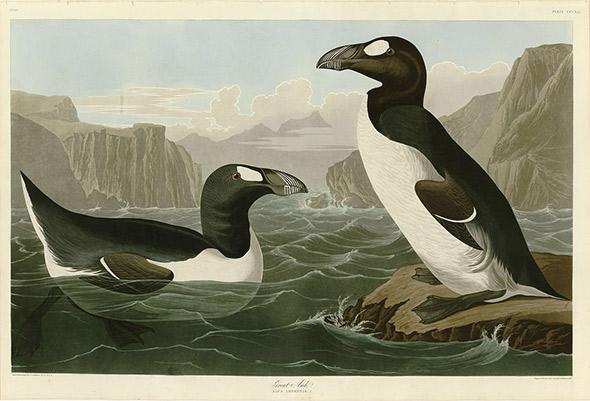

But cases like the rediscovered New Guinea big-eared bat should remind us of the sensitivity of small wildlife populations, and of our own uncertainty about population estimates in the field. Historical examples, too, such as the great auk, the Mexican elf owl (endemic to Socorro Island, Mexico), and the Ozark cavefish (all of which were pressured to some degree by scientific and amateur collectors in addition to other threats), further underscore the high stakes of taking individuals from small populations in the wild.

No scientist or conservationist today would deny the importance and value of describing a new species or confirming the return of one thought lost to extinction. But scientists also have a powerful ethical responsibility to minimize any and all adverse ecological impacts of their work. That holds true even for (and perhaps especially for) vital research to authenticate a species’ existence—or to verify its welcome reappearance in the wild.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.