Five weeks into the search for missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, more than $30 million has been spent scouring great swatches of the southern Indian Ocean. Yet searchers have still not found a single piece of physical evidence such as wreckage or human remains. Last week, Australian authorities said they were confident that a series of acoustic pings detected 1,000 miles northwest of Perth had come from the aircraft’s black boxes, and that wreckage would soon be found. But repeated searches by a robotic submarine have so far failed to find the source of the pings, which experts say could have come from marine animals or even from the searching ships themselves. Prime Minister Tony Abbott admitted that if wreckage wasn’t located within a week or two “we stop, we regroup, we reconsider.”

There remains only one publically available piece of evidence linking the plane to the southern Indian Ocean: a report issued by the Malaysian government on March 25 that described a new analysis carried out by the U.K.-based satellite operator Inmarsat. The report said that Inmarsat had developed an “innovative technique” to establish that the plane had most likely taken a southerly heading after vanishing. Yet independent experts who have analyzed the report say that it is riddled with inconsistencies and that the data it presents to justify its conclusion appears to have been fudged.

Some background: For the first few days after MH370 disappeared, no one had any idea what might have happened to the plane after it left Malaysian radar coverage around 2:30 a.m., local time, on March 8, 2014. Then, a week later, Inmarsat reported that its engineers had noticed that in the hours after the plane’s disappearance, the plane had continued to exchange data-less electronic handshakes, or “pings,” with a geostationary satellite over the Indian Ocean. In all, a total of eight pings were exchanged.

Each ping conveyed only a tiny amount of data: the time it was received, the distance the airplane was from the satellite at that instant, and the relative velocity between the airplane and the satellite. Taken together, these tiny pieces of information made it possible to narrow down the range of possible routes that the plane might have taken. If the plane was presumed to have traveled to the south at a steady 450 knots, for instance, then Inmarsat could trace a curving route that wound up deep in the Indian Ocean southwest of Perth, Australia. Accordingly, ships and planes began to scour that part of the ocean, and when satellite imagery revealed a scattering of debris in the area, the Australian prime minister declared in front of parliament that it represented “new and credible information” about the fate of the airplane.

The problem with this kind of analysis is that, taken by themselves, the ping data are ambiguous. Given a presumed starting point, any reconstructed route could have headed off in either direction. A plane following the speed and heading to arrive at the southern search area could have also headed to the north and wound up in Kazakhstan. Why, then, were investigators scouring the south and not the north?

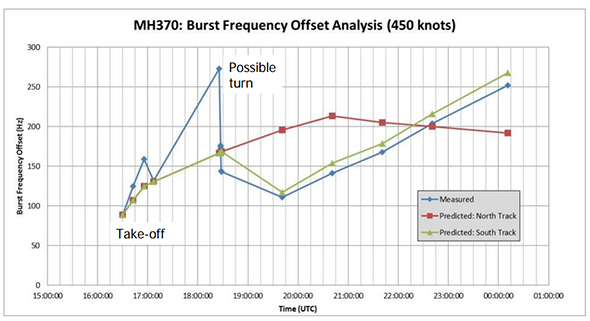

The March 25 report stated that Inmarsat had used a new kind of mathematical analysis to rule out a northern route. Without being very precise in its description, it implied that the analysis might have depended on a small but telling wobble of the Inmarsat satellite’s orbit. Accompanying the written report was an appendix, called Annex I, that consisted of three diagrams, the second of which was titled “MH370 measured data against predicted tracks” and appeared to sum up the case against the northern route in one compelling image. One line on the graph showed the predicted Doppler shift for a plane traveling along a northern route; another line showed the predicted Doppler shift for a plane flying along a southern route. A third line, showing the actual data received by Inmarsat, matched the southern route almost perfectly, and looked markedly different from the northern route. Case closed.

Courtesy Malaysia Airlines

The report did not explicitly enumerate the three data points for each ping, but around the world, enthusiasts from a variety of disciplines threw themselves into reverse-engineering that original data out of the charts and diagrams in the report. With this information in hand, they believed, it would be possible to construct any number of possible routes and check the assertion that the plane must have flown to the south.

Unfortunately, it soon became clear that Inmarsat had presented its data in a way that made this goal impossible: “There simply isn’t enough information in the report to reconstruct the original data,” says Scott Morgan, the former commander of the US Air Force Rescue Coordination Center. “We don’t know what their assumptions are going into this.”

Another expert who tried to understand Inmarsat’s report was Mike Exner, CEO of the remote sensing company Radiometrics Inc. He mathematically processed the “Burst Frequency Offset” values on Page 2 of Annex 1 and was able to derive figures for relative velocity between the aircraft and the satellite. He found, however, that no matter how he tried, he could not get his values to match those implied by the possible routes shown on Page 3 of the annex. “They look like cartoons to me,” says Exner.

Even more significantly, I haven’t found anybody who has independently analyzed the Inmarsat report and has been able to figure out what kind of northern route could yield the values shown on Page 2 of the annex. According to the March 25 report, Inmarsat teased out the small differences predicted to exist between the Doppler shift values between the northern and southern routes. This difference, presumably caused by the slight wobble in the satellite’s orbit that I mentioned above, should be tiny—according to Exner’s analysis, no more than a few percent of the total velocity value. And yet Page 2 of the annex shows a radically different set of values between the northern and southern routes. “Neither the northern or southern predicted routes make any sense,” says Exner.

Given the discrepancies and inaccuracies, it has proven impossible for independent observers to validate Inmarsat’s assertion that it can rule out a northern route for the airplane. “It’s really impossible to reproduce what the Inmarsat folks claim,” says Hans Kruse, a professor of telecommunications systems at Ohio University.

This is not to say that Inmarsat’s conclusions are necessarily incorrect. (In the past I have made the case that the northern route might be possible, but I’m not trying to beat that drum here.) Its engineers are widely regarded as top-drawer, paragons of meticulousness in an industry that is obsessive about attention to detail. But their work has been presented to the public by authorities whose inconsistency and lack of transparency have time and again undermined public confidence. It’s worrying that the report appears to have been composed in such a way as to make it impossible for anyone to independently assess its validity—especially given that its ostensible purpose was to explain to the world Inmarsat’s momentous conclusions. What frustrated, grieving family members need from the authorities is clarity and trustworthiness, not a smokescreen.

Inmarsat has not replied to my request for a clarification of their methods. This week, the Wall Street Journal reported that in recent days experts had “recalibrated data” in part by using “arcane new calculations reflecting changes in the operating temperatures of an Inmarsat satellite as well as the communications equipment aboard the Boeing when the two systems exchanged so-called digital handshakes.” But again, not enough information has been provided for the public to assess the validity of these methods.

It would be nice if Inmarsat would throw open its spreadsheets and help resolve the issue right now, but that could be too much to expect. Inmarsat may be bound by confidentiality agreements with its customers, not to mention U.S. laws that restrict the release of information about sensitive technologies. The Malaysian authorities, however, can release what they want to—and they seem to be shifting their stance toward openness. After long resisting pressure to release the air traffic control transcript, they eventually relented. Now acting transport minister Hishammuddin Hussein says that if and when the black boxes are found, their data will be released to the public.

With the search for surface debris winding down, the mystery of MH370 is looking more impenetrable by the moment. If the effort to find the plane using an underwater robot comes up empty, then there should be a long and sustained call for the Malaysian authorities to reveal their data and explain exactly how they came to their conclusions.

Because at that point, it will be all we’ve got.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.