The major winter storm that barreled across the country this week may be over, but storm clouds are still brewing over the future of the Weather Channel—America’s most popular weather source on television.

The channel is in the midst of an all-out brawl with DirecTV, which dropped TWC from 20 million households on Jan. 14 after a carriage dispute. Arguing that it provides critical, life-saving information, the Weather Channel had demanded a penny more per subscriber. Given TWC’s flagging viewership, DirecTV thought that was too much money—and, moreover, criticized TWC for straying from its core mission of 24/7 weather coverage and for choosing instead to air too much reality TV. Direct talks between the parties have ended, and now they’re fighting the battle in the media.

The Weather Channel has gone on the offensive, instituting what amounts to a scorched-earth policy and daring weather nerds nationwide to take sides. It’s even encouraged viewers to appeal to Congress on the grounds that lives are at stake. (In truth, nearly all its observational and predictive weather data already comes from public sources via the National Weather Service, including satellites, radars, weather models, and real-time current conditions.)

On Monday, in an interview with CNN’s Brian Stelter, Jim Cantore, arguably the most famous meteorologist on TWC, doubled down on that argument, saying, “I really think, when you kind of look at the Weather Channel overall, and you think about what happens before a storm, whether you’re an emergency manager’s office, whether you’re the National Weather Service or a local TV station, your first hint at what’s to come is from the Weather Channel.” That statement angered many government meteorologists and set off a social media firestorm.

Jim has since backtracked from his statement.

Then, on Wednesday, the Weather Channel took out full-page ads in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post, with a message from CEO David Kenny to DirecTV demanding the company pay former TWC viewers’ cancellation fees if they want to change providers. The ad also plugged a new website asking current DirecTV subscribers to switch. Conversation about the full-page ads exploded on Reddit, with not many people taking TWC’s side.

DirecTV is not the only threat that TWC is facing. Carriage contract negotiations are coming up soon for other providers as well. Checking the weather forecast is the sixth most commonly reported online activity, ahead of reading the news or getting medical info. That’s a big deal: In the future, mobile, Web, and social media will be people’s go-to sources for weather info. For now, local TV and TWC still dominate, but there are alternatives to the Weather Channel even today. WeatherNation—the channel DirecTV replaced TWC with—takes a much more “just give it to me straight” approach to broadcasting the weather, which some people clearly prefer to the sometimes breathless coverage of TWC.

The dispute crystalizes a discussion that’s long puzzled meteorologists and weather fans: What happened to the Weather Channel?

In my view, the appeal to Congress is a window into the Weather Channel’s inner workings: It’s getting desperate. The channel already sometimes leads viewers to believe it is a quasi-official source of information—with, for instance, its recent decision to create its own winter storm names. It’s not. It’s not even a reliable source of weather analysis anymore. Sure, you can get a steady stream of local temperatures and forecasts on TWC now even during commercials or Highway Thru Hell or Freaks of Nature, but you can do the same thing—wherever you are—with a quick check of the lock screen on your phone. In the 1990s, I watched the Weather Channel for an informed, well-reasoned, slightly nerdy take on the weather, by a real, live person. Now, I have the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang and Twitter. Whether the Weather Channel’s business model will survive the rise of the mobile Web is an open question.

In light of all this, the Weather Co. CEO David Kenny agreed to chat with me by phone on Wednesday about the Weather Channel’s place—past, present, and future—in the meteorological and media landscape. Kenny has been in his role since January 2012. Prior to the interview, I reached out via Twitter to crowdsource a few questions. Where possible, relevant Twitter questions I received are linked within my questions below. (Note: The interview has been lightly edited and condensed.)

Slate’s Eric Holthaus: Between the DirecTV spat and Cantore’s comments about the National Weather Service, it looks like you have a PR disaster on your hands.

Weather Co. CEO David Kenny: Let me be unequivocal that we have a real respect for NWS and NOAA [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] broadly. Whenever we’re in the field, we go to their field offices and have them on air whenever we can. Since 1982, we’ve invested millions of dollars in building a system to display NWS watches and warnings within minutes on a local basis. Folks with vision and hearing problems can access those weather alerts on the Weather Channel.

Now, that doesn’t make us special, but it does make us part of the nation’s weather communication backbone. Sometimes when you’re angry you speak too quickly, and I want to assure you there’s a great, healthy respect for all members of the weather community here at the Weather Channel.

That said, when you consider the sources for weather information on television, we do have a bigger team, we do send people to the field. We view ourselves as additive to what you can get from the NWS, and it’s helpful to have that extra source.

Holthaus: Why should Congress care about your dispute with DirecTV?

Kenny: We speak with Congress often, and we are big advocates for the right appropriations to make the weather infrastructure in the U.S. second to none, the best in the world.

I do think Congress, more importantly citizens, should be concerned when they [DirecTV] are making unilateral decisions. TV matters when safety is at stake. There is more you can do to prepare yourselves. Our partnerships with FEMA, the American Red Cross, to get safety information out to people in a timely manner is a critical part of severe-weather communication. And, after the storm passes, we test to see what people did with our information and to see if it’s effective, and we share that research.

Holthaus: So, is the current dispute with DirecTV an existential risk to your company?

Kenny: No. Television is important to us, but we have a business with a very strong and diverse base.

Holthaus: As someone who grew up obsessed with the Weather Channel in a small town in Kansas and couldn’t wait for the “Tropical Update” at 58 minutes past the hour, there’s a certain lack of seriousness that I see on the current incarnation of the Weather Channel, and the reality TV programming is pretty annoying when there’s life-threatening weather going on somewhere.

Is it just a pipe dream to want my old Weather Channel back? The dependable, fun, geeky take on what some people think is a boring subject but we both know is incredibly interesting and very important?

Kenny: We have to be careful that [our reality TV programming] doesn’t get too grandiose. Everyone is here because they love the weather. We absolutely don’t distract ever from the weather story.

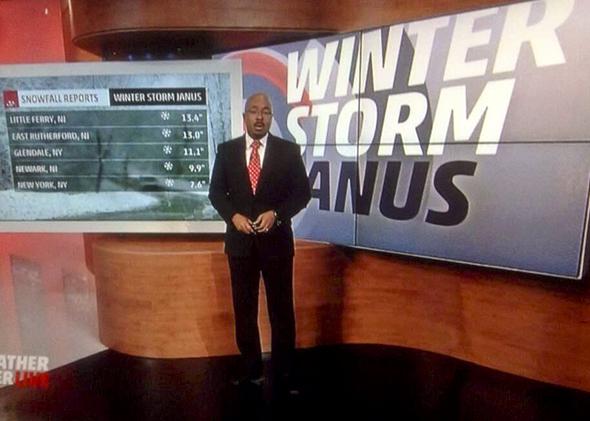

We are firmly behind the concept of a weather-ready nation [a NOAA/NWS initiative to prepare for increasingly frequent severe weather]. That is always our focus. For example, Tuesday, with Janus, we were full-live on air. There is no substitute for a live story. We don’t tape-delay to the West Coast for that reason. A weather alert that comes one hour late is useless. But I can’t say we have the right answer on this.

When I got here, in the pipeline, there was a lot [of programming] that I wasn’t a big fan of. We asked our viewers what they wanted and did a major relaunch back in November with a renewed focus on 24/7 weather information. You should never turn on TWC and not get basic weather, even during commercials. We can now pre-empt some of the country on a local basis when there’s breaking weather.

But the Weather Channel has a very broad base, and what we found is that when people watch weather stories with heroism, like Coast Guard Florida, they say, “Wow, that weather is more serious than I imagined, and these great men and women have the solution.”

We have a new show starting called Building Invincible, focused on upgrading our country’s infrastructure in the face of increasingly severe weather. What should Miami do to prepare for sea level rise? How are building codes working? How do we make sure coastal Louisiana doesn’t get wiped out every four years? Are they live weather? No. Are they stories that are about the weather and how we react to it? Absolutely.

Our programming is about being able to tell the weather story on a day when the weather is not life-threatening.

Holthaus: But there’s always weather going on somewhere, right? For example, the drought in California right now is life-threatening, even though it’s not a tornado barreling through a neighborhood.

Kenny: I respect that. The problem with TV is you can’t serve everybody. I don’t think the Weather Channel is the only answer. We’re complementary with other channels, including digital. The bottom line is, reality television on the Weather Channel needs to be based in science and storytelling.

Holthaus: The Weather Channel’s decision to name winter storms has been controversial. I get it—there’s a certain appeal to knowing what to call the beast of Mother Nature that just ruined your commute home. But some say unilateral winter storm naming is an arrogant ratings grab and not really necessary scientifically. The National Weather Service has refused to adopt the practice. Where do storm names go from here?

Courtesy of Brian Kargus

Kenny: I’m a nerd, and we’ve seen both types of responses to our storm names. We’ve found that the positive feedback has outweighed the negative.

The decision to name a storm is absolutely scientifically based, and the decision is made by Tom Niziol, Stu Ostro, and Peter Neilley, scientists with decades of experience. At least 30 million people must be impacted, and NWS watches and warnings must be likely to happen. We’re not trying to front-run the National Weather Service.

Now, we’ve launched a forum at the American Meteorological Society to discuss winter storm naming. That’s where we all belong. I’d love us all there, discussing this specific question.

What we do know is the most recent winter storms created an enormous amount of social communication. The fact that you can aggregate [all the impacts of] a storm like “Janus” is a very powerful communications tool. This week, the Navy used it, local officials used it. This is not a ratings thing, because then we’d make it proprietary. We don’t want to own these names. I hope some day it gets done by someone other than us, but I also think it’s worth it for us to continue to innovate.

This year I feel much better that people are picking it up. It gets people more interested in weather, and that’s a good thing.

Holthaus: On climate change, I know you were the only network to broadcast in full the president’s speech last summer announcing the White House’s Climate Action Plan. But for some reason, there seems to be the impression, at least on Twitter, that the Weather Channel isn’t doing much in the way of climate coverage.

Kenny: I hope they’ll watch more. We’re doing it well, and we’re doing it scientifically.

This week, I was supposed to be speaking in Davos but had to cancel due to the situation with DirecTV. DirecTV has so unfairly yanked us away from our viewers, which reduces our ability to speak about this important issue in the future. We need to help get the rest of the world to stand up. The science is clear, but science takes time to understand. We’ve got billions of people on the planet, trying to understand how it works.

I don’t think there’s a place for politics on the Weather Channel. When you jump to the politics, you’re really doing a disservice. [Talking about climate change] will work better when more people are talking about the scientific linkage and not talking about the politics. We’re part of a broader fabric; [it] would be good if we all worked together on this. I view us as scientific journalists.

Holthaus: You just spoke of the billions of people on the planet, trying to understand weather and climate. As you can tell, I’m a big fan of Twitter and crowdsourcing content on sunny days from around the world. What would you imagine the hip, 21st century, Internet version of TWC to be like? Let the average person say what weather means to them? Seems like the Weather Channel might do well internationally, as a partner with meteorology services around the world.

Kenny: We are absolutely committed to understanding the role of crowds in observation and validation of weather data. That’s one of the big reasons we brought the Weather Underground on board. We love its network of personal weather stations. That data has made our models better. We’d love to expand the global network of personal weather stations, especially in the Southern Hemisphere and in poorer nations. But we have to make sure it’s good data.

We’re starting to experiment with mobile apps that allow our users to tell us if the forecast is accurate or not, to try to use that information to make our forecasts even better. That’s important both on the science and the storytelling. We’ve tried to make more room for our viewers themselves on air.

What we like about social media is that it gives an instant pulse on what people are experiencing. If we can find ways to help Twitter with nowcasting, I think that would be a naturally fitting partnership.

Holthaus: Anything else?

Kenny: You know, what’s interesting about these questions is that it’s clear that people, even if they’re upset, feel like they have part ownership of the Weather Channel. They grew up with it. Hearing their feedback makes us more effective as a communication device. I’m grateful for the positive and negative feedback and people’s engagement.

I’ve calmed down a bit over the last few days, but I want to make it clear that our fight is with DirecTV and not with anyone in the weather world. The assertion [by DirecTV] that weather is a commodity is an insult to anyone who dedicates themselves to the science. I don’t want to see it attacked. We’re committed to the same thing as everyone else: getting weather information to people who need it.

* * *

Just one Weather Channel supporter showed up on my Twitter feed when I sent a call out for questions. Upon urging from the Weather Channel, she sent along a video she made that she titled “Why I Want the Weather Channel.”

The gist of her statement was, “It feels like I’ve lost my best friend.” As for me personally, I can sympathize. But, I think I lost the Weather Channel years ago.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.