The world didn’t end last month with the “Mayan apocalypse.” But we still need to think about how close total annihilation caused by nuclear weapons could be.

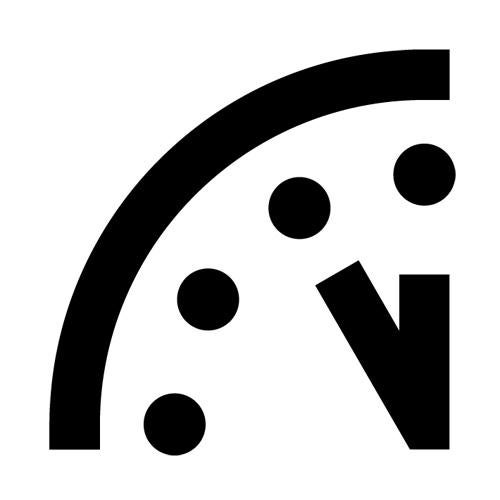

Each year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists considers resetting the Doomsday Clock, which gauges the state of existential global threats to civilization. (Disclosure: I must admit to being co-chair of the bulletin’s Board of Sponsors.) The setting of the clock is, of course, a somewhat subjective activity, and one can argue with the choices made. When it was first released in 1947 to graphically publicize the threat nuclear weapons and a nuclear arms race pose to humankind, the clock was set to seven minutes to midnight. The closest it’s ever been to predicting annihilation came in 1953, at two minutes to midnight. In 1991, it was set to its furthest point so far, 17 minutes to midnight.

A major change in the procedure for setting the clock took place in 2007 (coincidentally, when I took my current position on the bulletin’s board). No longer were nuclear weapons the only threat we would monitor: We would also take into account the growth of potentially destructive biotechnology and the threat of climate change. Exactly what time the clock is set to is less important than the trends we can observe—whether we are moving toward or away from disaster. Last January, the clock was moved forward one minute closer to midnight, in part because, while there was progress in several key areas, hopes that that Barack Obama would drive progress in climate change and nuclear proliferation were not met. This year, in large part because of continued lack of progress, the clock remains at five minutes to midnight—which is not good.

For many, nuclear weapons have fallen off the political radar entirely, except for the ongoing worry about terrorists or rogue states gaining access to nuclear materials and delivery systems.

But the fact remains that the governments of the world already possess perhaps 20,000 nuclear weapons—enough to destroy the world several times over—and we’ve seen little progress in the quest to rein in this danger. So nukes remain the Doomsday Clock’s primary focus. As such, whether the clock moves in 2014, and in which direction, could depend in part on a policy battle now heating up in Congress.

The current nuclear states have made a commitment to reduce their stockpiles, and the Obama administration has made some progress in that vein—for instance, early in his administration, by ratifying the START treaty, which calls for reductions in arsenals in both the United States and Russia. But the heart of encouraging nonproliferation is for nuclear states to behave as though they don’t view these weapons as a long-term strategic resource. If they continue to do so, how can we convince states that do not yet have nuclear weapons to resist pursuing them? It is a tragedy and a travesty that the United States, four years after Obama’s first election, has still not ratified a Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, for example. Doing so would signal that we do not intend to develop new nuclear weapons technologies that might make their use somehow more palatable.

But now a looming crisis may finally force renewed public discussion on our nuclear weapons arsenal, and on the role it plays in our national security infrastructure.

In 1946, the very scientists who first founded the bulletin lobbied successfully to have atomic energy (including weapons) placed under civilian, rather than military, control. They were worried that the military would not only be more inclined to use these weapons, as they had against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but what little transparency and public accountability remained in this area would evaporate. As a result, the Atomic Energy Agency was formed.

In the intervening 65 years, our nuclear weapons complex has grown tremendously in size and cost, and managing and maintaining its infrastructure and security seems to have been beyond the capabilities of any government agency. In 1999 the National Nuclear Security Administration, located inside the Department of Energy, was created to manage all aspects of nuclear development, including managing the national laboratories in which research and production of nuclear weapons is carried out.

In 2012, a bevy of problems, including excessive cost overruns, deteriorating facilities, and concerns over security caused Congress to consider legislation that would transfer control of safety, security, and financial compliance of nuclear research from the Energy Department to civilian contractors. However, after a supposedly highly secure weapons site at Oak Ridge was penetrated by peace activists (including a nun), one options now under consideration is transferring the NNSA to the Defense Department. The Senate passed a resolution to create an advisory panel to investigate management of the NNSA. A final report is expected by February 2014.

If the NNSA is transferred to the military, it will be the first time since the Manhattan Project that management of our nuclear weapons complex will not be in civilian hands. I personally find this prospect worrisome, but the issue is not black and white. One might think initially that, under military jurisdiction, the nuclear program will only grow and become more costly. However, it’s not unlikely that the nuclear program would face cuts, as the armed forces have many other spending priorities. Moreover, removing nuclear weapons from the purview of the DOE would allow that department to actually focus on one of the biggest challenges the United States faces in the 21st century: conversion to sustainable and economically viable new energy sources.

The situation is thus complex, and there may be no good solution. Maintaining our current arsenal is incredibly expensive, and in the current economic climate, the cost simply to update the infrastructure is at best unpalatable. If this current dilemma gets played out openly in Congress, and hopefully in the media, it could pave the way for real progress in disarmament. As has so often occurred, peace might break out not for the right reasons, but because the alternative is simply no longer economically viable.

Perhaps the upcoming debate over the NNSA’s future will finally re-engage the public with this issue—something that is long overdue. Then maybe we can move the Doomsday Clock back, further away from midnight.

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.