A few months ago, I used the shale gas boom to argue that our innovation system is broken. We constantly unleash poorly understood powers and scramble to ride out the unintended consequences. My basic point was that we need to be more precautionary—when a new technological activity has some unknown possibility of causing harms, we ought to restrain the activity until cause-effect relations are better understood.

I assumed that this was the principled position (it is the precautionary principle, after all) and the alternative was rapacious corporate capitalism. But I later found out that in 2004, Ray Kurzweil and other transhumanists hatched the idea of “proaction” as an explicit and ethical counterweight to what they saw as the dangerous creep of precautionary technology politics. The futurist philosopher Max More went on to formulate the proactionary principle.

Whereas the precautionary approach adheres to the Hippocratic dictum of “above all, do no harm,” the proactionary adheres to the Faustian dictum of striving to overcome limits. The former demands knowledge before action. The latter creates a meshwork of technoscience by treating innovation as both social change and scientific experiment. More argues, “Being proactive involves not only anticipating before acting, but learning by acting.” This point can be put in engineering terms. A paradox of engineering is that it transforms the world precisely by not modeling all of its complexities. If we attempt to model everything we’ll never leave the drawing board. Testing designs in the real world is an essential component of the social learning process known as progress. According to this principle, the way we developed shale gas (indeed, the way we carry out innovation more broadly) is not just how things must be—it is the way they should be.

If we had followed a precautionary approach all along, More notes, “progress would have ground to a halt,” and we would have “no chlorination and no pathogen-free water; no electricity generation or transmission; no X-rays; no travel beyond the range of walking.”

The best way to handle emerging problems is to make adjustments along the way. One example is the list of “recommended technologies and practices” for shale gas development compiled by the EPA. Through ongoing real-world experiments, the industry is learning and adopting new techniques and practices that can boost both economic and environmental performance.

Two ideals lend the proactionary principle its ethical heft: utilitarian beneficence and freedom. Sure, some people might suffer from mistakes, but in the long run, innovation brings about the greatest good for the greatest number. This is so, of course, only as long as we are free try out new ideas. More portrays proaction as Ayn Rand for the 21st century: “[D]on’t cut off the hands of those who spread the seeds of the future.”

In the documentary Gasland, director Josh Fox never says anything good about natural gas. Even if drilling is polluting some water wells, it is also powering millions of homes and businesses. Thus, fairness is arguably a third ethical dimension of the proactionary principle: We ought not to tell a biased story about only the bad impacts of a new technology.

Yet as with Rand’s triumphant defense of the captains of industry, we should ask whether More’s principle is anything other than an ethical veneer on the process whereby the rich get richer. Is there substance here, or is this more neoliberal mumblespeak like strategic dynamism?

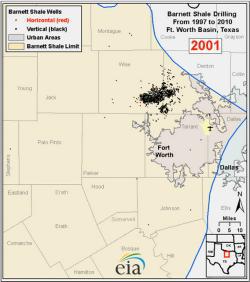

Courtesy the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Consider what More calls “the essence” of the proactionary principle: “Let a thousand flowers bloom! By all means, inspect the flowers for signs of infestation and weed as necessary,” but do not stifle “our freedom to learn.” Now look at this EIA animation of gas well drilling on the Barnett Shale. Here we see, not just a thousand but 15,000 gas wells blooming. Sure, it looks more like a bad case of measles than flowers. But the point remains that this is the essence of proactionary innovation at work. This massive industrial bloom occurred with very little up-front discussion of social, environmental, and even economic ramifications.

In proactionary terms, for roughly 10 years now we have been collecting data from this social experiment, looking for “signs of infestation” so that we can “weed” where necessary. One of the key components of the proactionary principle is “objectivity” (as opposed to “emotion”) in the assessment of risks. What seems to elude More, though, is that in the context of corporate capitalism, a proactionary approach to innovation undermines the conditions necessary for an objective appraisal of risks.

The natural gas industry is the player with the most money, political influence, and vested interest in the task of monitoring the impacts of drilling. It is anything but a fair and level playing field. Gasland’s Fox makes this case in his recent short “The Sky Is Pink.” He notes that the American Natural Gas Association hired Hill & Knowlton, the same PR firm that in the 1950s ran a misinformation campaign to dispel concerns about the health risks of smoking. Fox interviews Naomi Oreskes, who argues that this is yet another instance of a deep-pocketed industry acting as “merchants of doubt” to manufacture debates and controversies. The strategy is to create enough uncertainty about the impacts of fracking to discredit any call for strengthened regulations. There are no weeds!

Fox accuses the natural gas industry of concealing some of their own evidence of well casing integrity issues. And he notes the major political donations made to influential politicians by the industry. We can add to this picture the proprietary status of certain fracking chemicals and non-disclosure agreements that prevent landowners sharing information about accidents on their property. This all works against the ideal of objective risk assessment.

Concerned parents and neighbors have been scraping together a few thousand dollars to pay for air monitoring studies. The proactionary principle might laud such efforts as part of the learning process. But it is pitted against a Goliath of multi-billion dollar industry research and lobbying.

The precautionary principle may be technically naive in hoping that we could factor out all the bad consequences before they even happen. But it is politically naive to think that we can create billions of dollars of vested corporate interests around a new technology and then conduct a rational and fair process of assessing its risks.

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page You can also follow us on Twitter.