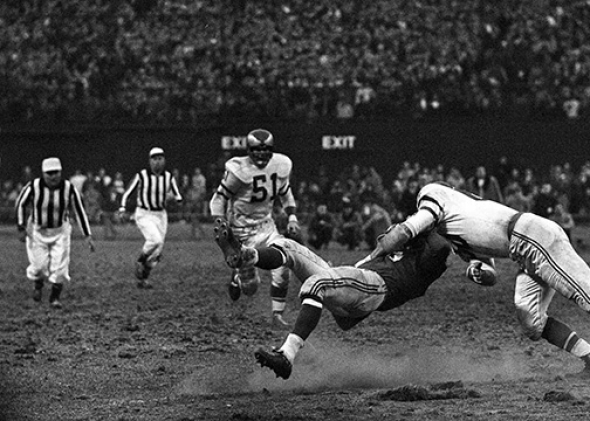

The Hit

Chuck Bednarik and the myth of the NFL’s most vicious tackle.

Photo by Kidwiler Collection/Diamond Images/Getty Images

Chuck Bednarik, the former NFL All-Pro who played both ways in three different decades for the Philadelphia Eagles—center on offense and linebacker on defense—died on Saturday at the age of 89.

Bednarik, who went by the nickname Concrete Charlie (because he also was a concrete salesman), was best known, and memorialized in obituaries, for a hit on New York Giants star halfback Frank Gifford on Nov. 20, 1960. The New York Times wrote that Bednarik “leveled [Gifford] with a blindside tackle to his chest after he caught a pass from quarterback George Shaw.” The Associated Press’ obituary said Bednarik “knocked out Gifford with a blow so hard that Gifford suffered a concussion and didn’t play again until 1962.” Yahoo said it was “one of the hardest hits the game had ever seen.” NPR called it “one of the most severe hits in the sport’s history.” The New York Daily News said it was “vicious.” “Bednarik’s right shoulder landed squarely under Gifford’s chin and sent him down in a heap,” the newspaper reported.

Last year Sports Illustrated’s Monday Morning Quarterback website said Gifford was “leveled” with “a forearm to the chest.” In 2013 Philly sports writer Ray Didinger said that Bednarik was “coming full speed in the opposite direction” when he hit Gifford.

So was it a blindside tackle to the chest? A right shoulder under the chin? Or a forearm to the chest? Was Bednarik moving at full speed? Did the blow itself knock Gifford out? Was it one of the hardest hits ever?

Let me respond to those questions: no, no, no, no, no, and no. Those answers are easily attainable by watching the grainy video.

Gifford catches a pass over the middle. He’s running gingerly across the icy field from left to right. Bednarik chases from about 5 yards behind and facing Gifford. Bednarik overpursues, and when Gifford cuts to his right to avoid him, Bednarik throws on the brakes and reaches back to intercept Gifford. The two collide, left shoulder to left shoulder. Bednarik’s left arm reaches across and stops Gifford’s forward progress. His right arm reaches across the back of Gifford’s shoulder pads, and Bednarik pushes him backward to the ground.

So: It’s not a blindside tackle, as the Times claimed; Gifford is running toward Bednarik, sees him, and tries to avoid him. Bednarik isn’t moving at full speed, as Didinger wrote; in fact, he’s barely moving at all. The initial contact isn’t to Gifford’s chest, as SI and others asserted. And contrary to the Daily News obit, Bednarik’s right shoulder makes no contact whatsoever with any part of Gifford’s body.

As NFL hits go, it’s not a particularly violent one. It’s an awkward one. An off-balance Bednarik blocks the much smaller Gifford’s path, and the collision sends Gifford down in banana-peel fashion. To be sure, Bednarik is a brick wall, and Gifford’s descent is dramatic and powerful. But the Eagle doesn’t appear to slam the Giant down; momentum, conservation of energy, and gravity do most of the work. And while Gifford was indeed concussed and knocked unconscious, it wasn’t from the force of the blow. As he has said repeatedly in the decades since, Gifford was hurt because his head whiplashed against the frozen Yankee Stadium turf. (He also has said he skipped the 1961 season not because of the injury but because he was offered a job in television.)

The always excellent sportswriter Peter Richmond, who co-authored The Glory Game, Gifford’s book about the 1958 NFL championship game between the Giants and the Baltimore Colts, wrote after Bednarik’s death that the notable feature of the play isn’t the animalistic violence attributed to it, but its restraint. “Bednarik actually moves his head away so as to not go head to head, then corrals Gifford by the shoulders,” Richmond writes. He added: “Maybe we should praise Bednarik for trying to set an example on the play, and not trying to hurt Frank.”

Richmond went on to note that what’s really interesting about the play is also what helped make it so iconic: the image of Bednarik poised over the passed-out Gifford pumping his first downward as if punching out the fallen player. Richmond called it the first taunt. But even that appears to be at odds with what happened. Bednarik always said he wasn’t celebrating having knocked out Gifford, but rather having forced a fumble that sealed the Eagles’ 17–10 victory.

After the hit, Bednarik gets up, looks for the ball, and, realizing the Eagles have recovered, points downfield with his right arm. The video stops before Bednarik makes the famous celebratory gesture. The photo looks to me like a fraction of a second that’s contrary to the reality of the full sequence. Immediately after the game, Bednarik insisted he wasn’t taunting. “I remember waving my fist as a victory signal,” he said in the Philadelphia Daily News. “I always do that on a play that means the game.” Though he told the story of the hit for dramatic effect, Bednarik for years maintained he wasn’t being cruel to Gifford. “If people think I was gloating over Frank, they’re full of you-know-what,” he once said.

“The Hit” or “the Tackle,” as the play came to be known, was a perfect piece of propaganda that the NFL set to ominous orchestral music and used to define itself as it soared in popularity in the 1960s and ’70s: tough, snarling, merciless, unspeakably violent. As a piece of history though, it’s the product of faulty memory, fish-tale exaggeration, and lousy reporting.

This transcript from Slate’s sports podcast Hang Up and Listen has been lightly edited for clarity.

Listen to the rest of the episode here: