Remember Zelmo Beaty

An obituary for Slate’s favorite basketball player.

On Saturday, long-time NBA and ABA center Zelmo Beaty died of cancer at the age of 73. For the last several years, Slate’s sports podcast “Hang Up and Listen” has ended each week with the words, “Remember Zelmo Beaty.” That motto was first uttered back in 2011, when the podcast featured a long conversation about the 1968 Sports Illustrated series “The Black Athlete: A Shameful Story.” On that show, the hosts interviewed Zaid Abdul-Aziz, who said it upset him that today’s NBA players don’t remember the greats of bygone days. Abdul-Aziz cited an appearance by Shaquille O’Neal on The Late Show with David Letterman, wherein O’Neal told the late-night host that he’d never heard of Zelmo Beaty. On this week’s edition of “Hang Up and Listen,” Stefan Fatsis marked Beaty’s passing by remembering the remarkable life and career of “Big Z.” An adapted transcript of the audio recording is below, and you can listen to Fatsis’ essay by clicking on the player beneath this paragraph.

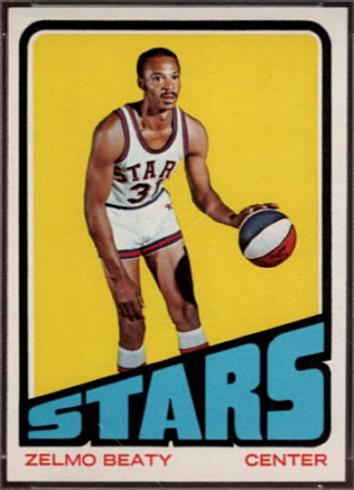

Courtesy of eBay

If David Letterman had quizzed Shaquille O’Neal about Mel Daniels or Walt Bellamy or even Artis Gilmore, I’m pretty sure we wouldn’t have used it as a catchphrase. But Zelmo Beaty, for those of us old enough to really remember him but young enough not to remember how good a basketball player he was, the name is what mattered.

But Zelmo—a Hebrew form of Solomon, by the way—was far more than just four hard syllables. He was the third pick in the 1962 NBA draft out of all-black Prairie View A&M. Future scouting legend Marty Blake, then the GM of the NBA’s St. Louis Hawks, was one of the few league executives who scouted the black colleges. “Everyone was saying, ‘Are you nuts? What have you been smoking?’ ” Blake recalled in an interview with Remember the ABA’s Dan Pattison.

A 6-foot-9, 225-pound center, “Big Z”— also known as “the Franchise”— had to bang against Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain, but he was good. He played seven solid seasons for the Hawks—six in St. Louis and one in Atlanta, averaging a double-double in all but his rookie year—before he decided to jump to the two-year-old American Basketball Association. The reason: the money. Zelmo said he never made more than $30,000 a season with the Hawks. The Los Angeles Stars of the ABA signed him to a four-year deal worth $800,000.

Free agency in sports was still years away, so Zelmo had to sit out a season in order to be released from his NBA contract. But during that season, the Stars were sold to Bill Daniels, a pioneer in cable television. Daniels moved the team to Salt Lake City, the population of which was literally 99 percent white. Beaty announced that he wouldn’t report if the team went to Salt Lake, in part because of tensions between black athletes and the Mormon Church, which didn’t let blacks serve as priests. Sports Illustrated reported at the time that that local leaders assured Daniels that his players “would be well treated.” Beaty and his wife Ann made their own visit, were satisfied with their housing options, and agreed to go. All of the other black players on the Stars followed.

The move worked. According to a highlight film of the Utah Stars’ first season, fans filled the modern Salt Palace because they “dig the action, the emotion of professional basketball.” Zelmo averaged 23 points and 16 rebounds, the Stars rolled to the 1970-71 ABA championship, and Zelmo was the playoff MVP.

The Stars eventually started an all-black lineup in all-white Salt Lake City. Beaty wound up playing four seasons there, and he deserves clear credit for making the city a viable place for pro basketball. As SI wrote in 1974, “Beaty quickly gained acceptance from the Utah fans, not only by leading the Stars to a championship in their first season, but by remaining quietly congenial and displaying his considerable innate dignity. He remains the only black player who owns a house in Salt Lake. And, according to other players, Beaty passed the word around the ABA that Utah was an all-right place to play.” The Stars would fold when the ABA and NBA merged in 1976, but the city regained a franchise when the Jazz moved from New Orleans in 1979.

Beyond the selfless play and personal dignity that made him a racial trailblazer in Utah, Zelmo was a labor activist who understood that times were changing in pro sports. He was a player rep in the NBA and the president of the ABA Players’ Association. He capitalized on the market leverage afforded by the rival ABA. He fought to get retired players better pensions. Athletes were beginning to assert control over their careers, and Zelmo wasn’t afraid to take on ownership.

In 1973, as his play was declining thanks to damaged knees—he had nine surgeries during his career—Zelmo got into a dispute with the Stars front office and sat out training camp and the start of the regular season. The team sued him for breach of contract and fined him $7,000. Zelmo countersued for $1.2 million.

"Basketball is a rotten business," Zelmo told SI. "They figure once they've drained all that you're worth, then they just dump you. Certainly here they've figured they've gotten all that's left out of No. 31. I didn't expect anything more than that—I've seen too many guys get washed out at the end—and I'm glad I didn't because I would've been setting myself up for a big disappointment."

After the team’s championship, Zelmo and the Stars lost in the next two conference finals and, in 1973-74, in the ABA finals, to Julius Erving’s New York Nets. Zelmo left the Stars and played one final season with the Lakers.

"I know for a fact that the players nowadays, earning the kind of money they're earning, don't have a sense of NBA history or an awareness about what the players before them did," Big Z told Remember the ABA’s Pattison. "But in fairness to them, I didn't have a sense of history, either, when I entered the league. I had to learn. And now I have a great deal of respect for the players who came before me.”

And that is why we remember Zelmo Beaty.

Correction, Sept. 23, 2013: Due to a production error, the trading card accompanying the piece was misidentified as a baseball card. It's a basketball card.