Moneygolf

Will new statistics unlock the secrets of golf?

At every PGA tournament, tucked away in a parking lot among the beverage trucks and television satellites, there's a white trailer with "ShotLink" emblazoned on the side. When I climb up the stairs and open the door, it's like stepping into a Dell computer—everything is gray and black. Five guys are looking at their laptop screens and making polite requests on two-way radios. They are talking to volunteers out on the course. The volunteers, about 200 of them, are using lasers to track every shot taken by every player.

I stand behind one of the ShotLink producers, Jason Stefanacci, and watch the shots roll in. The first round of the AT&T National is in progress, and 40 threesomes of pro golfers are making their way around the course. The par is 70, which means that the ShotLink team will record around 8,400 shots today. Since ShotLink became fully operational in 2003, the system has recorded more than 7 million golf shots: shots that have landed in trees, shots that have landed in spectators' laps, four-putt greens, double eagles.

Bundled together, those 7 million shots make up the richest dataset in sports. These shots teach us about the dynamics of competition: Do golfers really play worse when Tiger Woods is in the field? They teach us about choking: Do golfers who are in contention on Sunday miss more easy putts? And they help us answer golf-world conundrums that have always floated above the fairway, in the realm of hunches and best guesses: What separates an average pro from a champion?

We're in a golden age for golf research because the PGA Tour has opened ShotLink's books to researchers. Two professors at the Wharton school, for example, looked at 1.6 million tour putts and concluded that professional golfers are risk-averse. They examined putts for par and putts for birdie from the same distances and discovered that pros make the birdie putts less often. They suggest that pros leave these birdie putts short out of fear of making bogey, and then calculate that this bogey terror—and the resultant failure to approach birdie putts in the same way as par putts—costs the average tour player about one stroke per tournament.

It's insights like these that offer the provoking notion that a Moneyball-type revolution awaits golf. Of course, professional golf is not analogous to baseball, where a general manager spends his days trawling for inefficiencies, coldly evaluating the players on the field and trading for those he believes will perform the best. In baseball, the groundbreaking research of Bill James and his cohort was important not just because it showed fans and math buffs how baseball works. It also changed the way baseball was played as teams used Jamesian statistical insights to earn a tactical advantage.

There are no general managers on the PGA Tour. The golfer, with help from a caddie and coaches, must evaluate himself, searching for inefficiencies in his own game: Am I putting as well as the other guys? Is my wedge play up to snuff?

For touring pros, the new statistics and research can provide clear answers to these questions. When a player qualifies for the PGA Tour, he's given a laptop that he can use to access all of his stats. But is it a good idea for an elite athlete to fill his head with numbers? When I talked to PGA Tour players, many were skeptical about how stats could help them. Some, like U.S. Open champ Lucas Glover, were openly disgusted.

Me: "Hey, Lucas, do you ever look at your ShotLink stats?"

Lucas (South Carolina drawl): "Ab-so-lutely not."

Glover went on to express a perception on tour that ShotLink is disorganized and often wrong. That may have been partly true in the system's early years, but ShotLink is now a tight ship. I watched as the ShotLink producers corrected errors in real time and asked volunteers to verify any shot that looked out of whack. Besides, even if a few errors slip into ShotLink during a tournament, it's hard to ignore 7 million shots. Those shots are going to tell a true story, perhaps one that a golfer may not want to hear.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are players who have truly scrutinized the data to find holes in their game. I spent a long time on the range talking stats with Chris Stroud, a young Texan looking to make his name on the PGA Tour. He prints out all of his ShotLink numbers at the end of the year and analyzes them with his coaching team to figure out his weaknesses. This year, he noticed his putting, chipping, and bunker play were lacking, so that's where he put in the majority of his practice time.

But even the pros who told me they looked at ShotLink appeared a little confounded by it. "I try to simplify everything," Stroud told me, whereas ShotLink makes the game seem more complicated. After all, the system features 47 stats just for shots off the tee. It can be difficult to locate the meaning in that sea of numbers, and it's not surprising that so many pros find it easier just to rely on their own instincts. This is where the new golf research comes in: Analytical minds who love the game are on a quest for better statistics, numbers that reflect what is happening on the course and can be easily grasped by players and fans alike.

In this effort, golf researchers follow in the footsteps of the pioneering attempt to study golf. It took place in the 1960s and was led by Sir Aynsley Bridgland, an Australian industrialist who would recall later in life that he had three ambitions as a young man: "To own a Rolls-Royce, to be a millionaire, and to be a scratch golfer." He accomplished all three, "and he always said that it was the last of the three which satisfied him the most." After a visit to America, where he heard that professional golfers were participating in MIT-led "high speed photographic studies" of the game, Bridgland decided to attack the game scientifically. He assembled and helped bankroll a formidable team of scholars, including ballistics experts, physiologists, and Britain's first professor of ergonomics. In 1968, after five years of research, they published their results in a landmark book called Search for the Perfect Swing.

The British team helped answer fundamental questions about how the game is played. They described the golf swing as a double-pendulum and examined how the shape of the club head affects swing path and ball flight. They studied the ball itself, describing the aerodynamics of dimples and how the materials respond to the impact of the club. The book had an enormous influence on golf equipment companies, who began to hire physicists and materials engineers. (Karsten Solheim, the founder of Ping, was a big fan.) But the team was limited in its ability to answer basic questions of strategy—for example, is putting or driving more important for shooting a low score?

In our time, the search for the perfect swing has become coupled with the search for the perfect round. With GPS, laser surveyors, computers, and new mathematical strategies, we can analyze golf at a level of sophistication that Sir Aynsley Bridgland never could have imagined. Thanks to these tools, we are on the cusp of discovering the optimal way to play the game. Throughout this series, I'll explain the revolutionary research that may change the way you watch and play golf. I say "may" because golf has always been about balancing intuition and analysis. In the past, the game has leaned more toward the Zen, the mystical. In the sprit of our data-driven times, the game is about to get a lot more statistical.

Bad Lies: Why most golf statistics whiff and how to fix them.

Watch a golf tournament on television, and you'll hear the announcers explain why Tiger Woods or Justin Rose or Ernie Els is in the lead. "He's tops in the field this week in fairways hit," they might say. Or perhaps they'll point to his stellar driving distance, or his amazingly low number of putts per round, or his excellent birdie conversion rate. But none of those statistics—the ones we're told separate the champions from the also-rans—truly reflects why golfers win and lose. At worst, they're actively misleading, giving us the wrong impression of why the best players in the game succeed.

For example, a common measure of a player's driving accuracy is the percentage of times he reaches the fairway on his first stroke. The PGA Tour's current leader in driving accuracy, Omar Uresti, has hit the fairway on 76 percent of his tee shots. But even if a golfer cracks his drive into the fairway 76 percent of the time, you can't assume that he had a good driving day. What if his misses were so atrocious that they went into the deep rough, inflating his scorecard with a bunch of recovery shots? That's the weakness of the driving accuracy stat: In recording errant drives, it doesn't distinguish between a shot that trickles just off the fairway and one that hits an unsuspecting fan in the butt.

The pros are aware of the holes in the standard stats. When I talked to players at the AT&T National, the stat that came most under fire was greens in regulation. GIR presumes to measure the accuracy of a golfer's iron play—reaching a green in regulation means landing the ball on the green in three strokes on a par 5, two strokes on a par 4, and one stroke on a par 3. Michael Letzig, a lanky, affable pro from Missouri, recalled a shot that he hit on a long par 3 that landed five feet away from the hole—except the ball was on the fringe. That counts as a missed green. If you go by GIR, Letzig's shot was worse than one that landed on the putting surface, 100 feet from the cup.

Mark Broadie, a professor at the Graduate School of Business at Columbia and an avid golfer, understood the fundamental problem with golf statistics: They don't factor in distance and location. Professor Broadie spends most of his time studying the financial markets. He knew that he could take the same mathematical tools that he uses to value an unusual security and apply them to golf. But first he needed the data. Around 10 years ago, he started keeping track of the rounds that he played with his friends and colleagues. He didn't just record standard stats such as his total number of putts and the number of fairways he hit. He created something that, with the PGA Tour's ShotLink not yet in existence, nobody had thought to construct: a database that allowed him to enter the precise coordinates of every shot that he and his golf buddies struck.

Broadie's collection has since grown to include more than 65,000 shots from golfers as young as 8 and as old as their 70s, with rounds as low as 61 and as high as 150. Thanks to his golf shot database, Broadie was able to do away with the old-fashioned, simplistic stats we hear about on TV and figure out how the game is truly played. Just as baseball's statistical pioneers overthrew the tyranny of ERA and RBI by developing more meaningful metrics, Broadie saved golf from GIR with a concept called "shot value."

The foundation of shot value is the idea that, once you have a huge database of golf shots, it's possible to set a benchmark for performance from every position on the course. Broadie uses the scratch golfer (someone who shoots par) as his benchmark. Using the data he collected, he determined how many strokes it would take a scratch golfer, on average, to get the ball in the hole from every inch of turf—everywhere from the first tee to the bunker that guards the 18th green.

Imagine that you are standing in the fairway with a 150-foot approach shot to the green. You look down, and instead of a yardage marker, you see a stake with the number 2.5. That's the average number of strokes it takes a scratch golfer to hole out from that spot. Picture these same sorts of markers everywhere. The tee box on a difficult par 4 may say 4.6. A 60-yard sand shot may have a 2.7 marker, and so on.

Once you have a benchmark "fractional par" value for every point on a course, you can figure out the value of every single shot. In a paper presented at the World Scientific Congress of Golf (PDF), Broadie gives the example of a 140-yard par 3 that plays, for the scratch golfer, like a par 3.2. Let's say a golfer hits his tee shot to within 14 feet, moving from a location where it takes an average of 3.2 strokes to hole out to a spot where it takes an average of 1.8 strokes to finish. The simple arithmetic to determine the value of the shot: 3.2 - 1.8 - 1 (for the stroke that was taken) = 0.4. The superb approach shot has given our fictional golfer a four-tenths of a stroke advantage over a scratch golfer.

Like all revolutionary concepts, shot value takes a few moments to get your head around. Perhaps the easiest place to grasp it is the green. Let's return to that 14-foot putt for birdie on the par 3. According to Broadie's research, a scratch golfer makes 14 footers about 20 percent of the time, gets home in two about 80 percent of the time, and rarely three putts. That gives the 14-foot putt a fractional par of 1.8—if you sink the putt, you pick up eight-tenths of a shot. If you just miss it, you lose two-tenths of a stroke.

While we write down our golf scores in whole numbers, Broadie's concept of shot value reinforces that a golfer loses or gains fractional advantages on every swing. This aligns with what it's like to be on an actual golf course. Every hole has certain places where it's great to land your ball—a spot where there's a good angle to the green, or an easy uphill putt—and other spots where you're "in jail," or out of bounds, or blocked by a tree. Hitting a shot to a good position is obviously more valuable than hitting it to a bad position. What shot value does is tell you exactly how much more valuable.

The beauty of shot value is that you can add it up. How many strokes is a golfer gaining or losing due to his approach shots? How about his putting? It's simply a matter of tallying individual shot values and comparing the results to the player's peers'.

In order to see shot value in action, Broadie analyzed for me how Tiger Woods won the 2008 Arnold Palmer Invitational at the Bay Hill Club. Tiger was at the height of his powers during this tournament—a golfing superhero who looked nothing like the all-too-mortal duffer who finished a breath out of last place at Firestone last week. The victorywas capped by this famous highlight:

Tiger is standing over a 24-foot putt for birdie. If he misses, he will enter a playoff against Bart Bryant. If he makes it, he will win his fifth consecutive tournament and tie Ben Hogan on the all-time wins list. As Tiger reads the break, the announcers unleash a series of statistical insights. "Probably means nothing right now, but he is 0 for 21 this week on putts over 20 feet," says color analyst Johnny Miller.

Tiger strokes the putt. The ball slides toward the hole … rolling, rolling … it's in! Tiger throws his hat onto the turf, then does a double fist pump. "Hello, Ben Hogan!" shouts play-by-play man Dan Hicks. Bart Bryant shakes his head in the scorer's booth. The crowd walks to the clubhouse, marveling at another example of Tiger's greatness in the clutch—he'd saved his best putt of the week for the 72nd hole.

Tiger's putt was undeniably clutch, but it was merely one of 270 shots that he hit during the tournament. Shot value tells us that it wasn't that lone act of skill on the last hole that earned Tiger the first-place check. Rather, the victory was achieved thanks to a series of small things he did to put himself in a position to sink that long putt. But what were these small things?

Broadie took all of the ShotLink data collected at the Arnold Palmer and figured out the shot value of each stroke. Let's go back to Tiger's tourney-winning 24-foot putt. Broadie's data shows us that an average pro golfer hits about 24 putts of longer than 22 feet in a standard four-round tournament. It's typical to sink two of these long putts per tournament. (Yes, that's right—the best golfers in the world make just two long putts per 72 holes.) Until that putt on the 72nd hole at Bay Hill, Tiger's long putting had been below average: As Johnny Miller indicated, he'd had 21 putts from longer than 22 feet, and he'd missed them all. If Tiger could have been even an average long putter, then he wouldn't have needed those 18th green heroics.

To figure out where Tiger gained on the field, Broadie compared his shot value measures with those of his four closest competitors: Bart Bryant, who finished second, and Cliff Kresge, Vijay Singh, and Sean O'Hair, who tied for third. Tiger beat them by 2.5 strokes—where did those strokes come from?

Tiger made his name on the PGA Tour with long drives, but at Bay Hill his driving cost him 2.4 strokes to Bryant and Co. throughout the four days of play. (Indeed, just like last week at Firestone, Tiger's driving was disastrous in the early rounds.) He also lost 2.8 strokes on approach shots from 100-150 yards out. His layup shots were also slightly subpar, dropping him another eight-tenths of a stroke. That puts him six strokes down.

But now we reach one of the strongest parts of Tiger's game: He excelled at approach shots from 150-250 yards out, allowing him to pick up an amazing eight strokes on his closest competitors. This matches the highlights of his play. On Saturday, he hit a 4-iron around a stand of trees to within two feet of the hole. And on the last hole of the tourney, Tiger summoned what he called "the best swing I made all week" to land a 5-iron from 177 yards on the green and set up the winning putt. (Even with all of his 2010 struggles, Tiger remains the world's best on long approach shots. As I wrote last month, "His remarkable ball striking from this range is what keeps him in tournaments when other departments of his game are lagging.")

Thanks to his superb long approach shots, Tiger is now two shots up as we turn to the short game. Broadie defines the short game as all shots from 100 yards and in, excluding bunker shots close to the green. Tiger loses two strokes in this department. This fits with the lowlights of Tiger's play, as when he hit a pitching wedge that flew the green and chunked a sand wedge that landed well short of the putting surface. Tiger's touch closer to the green was more assured. He gained four-tenths of a stroke from the sand.

As we finally get to putting, Tiger is fractionally ahead by 0.4 strokes. Even after that clinching putt on Sunday, his below-average long putting cost him four-tenths of a stroke. He also lost another stroke due to his relatively poor performance on putts between three and six feet. He's now one behind his nearest competitors.

Where Tiger pulls away once and for all is midrange putting. He was deadly from seven to 21 feet, gaining 3.5 strokes. Even more remarkable is that he achieved this advantage despite three-putting from inside seven feet on the 10th greenon Sunday.

In Broadie's final analysis, then, it was Tiger's long approach shots and midrange putting that "won" the tournament. So, it is ultimately fair to say that Tiger's win at Bay Hill can be partly attributed to his clutch putting—clutch putting on every single one of the 34 putts he took between seven and 21 feet. That last putt he rolled in from 24 feet just brought him closer to being an average golfer. And where did he pick up the most ground on his competitors? It wasn't on the green; it was far away from the hole, with an iron in his hands.

Broadie's analysis helps us answer a question that it's never really been possible to solve before: How do you accurately compare one player with another? Sure, there's always the final score at the end of 72 holes. But imagine if the kind of analysis that Broadie did at Bay Hill were applied to an entire PGA season. Instead of a confusing, aggregated stat like, say, "total driving," you could have a figure that truly shows who gains the most from their driving skill. You could then use this figure to make better predictions about whether a course would favor a player's strengths. You could also do what Broadie has done: challenge the conventional wisdom of golf that putting is the pre-eminent skill, the dividing line between greatness and failure.

In my next piece, I'll take a closer look at putting and the researchers who are trying to bring mathematical rigor to golf's most mystical skill.

The Dark Art of Putting: A new stat sheds light on golf's most mystical skill.

The green is golf's great stage. It's the place where the pros seem the most mortal, the most like us. They misread the breaks. They yip five-foot putts. They even four-putt in excruciating fashion. On the green, the pros can't really do anything special to the ball that an ordinary golfer couldn't do. Perhaps that's why golf announcers are at their most wide-eyed when talking over a putt. They'll tell us the putt's distance and then head for the self-help aisle and start talking about "mojo" and "attitude" and "momentum."

The players themselves are also in awe of putting. In an interview on an NYC rooftop with golf writer Stephanie Wei, alterna-pro golfer Ryan Moore breaks down the PGA Tour this way: "Really, when it comes down to golf, at this level, I mean, it really comes down to putting. As much as we all kind of want to complain about our ball striking, you know, that just distracts us from our putting … and that's probably really the reason we're not playing that good."

Putting, we're told, is a dark art of willpower and focus. But putting has accrued such mystique in large part because the stats are a mess. On Tuesday, I explained how Mark Broadie's shot value allows us to precisely measure how much putting or driving contribute to a player's score. A team from MIT has built on Broadie's work by developing a new putting stat for the PGA Tour called "putts gained per round." It's similar to Broadie's shot value but makes a few different decisions in how to set a benchmark putting standard for pro golfers. Putts gained per round is likely to be the stat that brings "moneygolf" to the masses—if all goes according to plan, it should be part of golf's television broadcasts starting next season.

Since the time of shepherds and brassies, prowess on the greens has been judged by the number of putts a player takes per round. That's fine as a rough guide, but it's easy to see where the stat falls short. Yes, a player with a low number of putts per round may be holing an absurd amount of putts. Or maybe he's missing a lot of greens, chipping it close, and knocking in a bunch of easy two-footers that anyone could make.

In order to get around this "missed green" problem, the PGA Tour has a related stat called putting average, which counts the number of putts taken on greens that a player hits in regulation. (That means landing the ball on the green with a chance to make birdie or better.) But putting average isn't precise either. If you consistently hit great iron shots, you'll land the ball closer to the hole, and you'll subsequently make more putts. The player who lands the ball farther away from the hole but is a world-beating putter will be hidden by the statistics. He's better on the greens, but you don't know it.

With ShotLink, the building blocks for an accurate putting statistic are almost right in front of us. ShotLink has the key pieces of information: where millions of putts started, where millions of putts ended up. But determining putting skill from these data requires some mathematical gymnastics. To that end, the Tour approached the MIT mathematicians, led by Douglas Fearing, and asked them to analyze the stats.

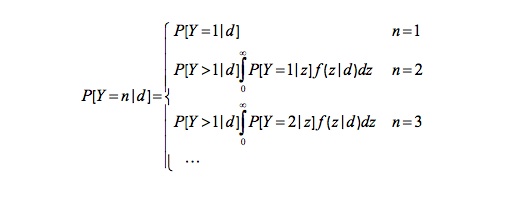

They came back with many equations. Here is what the equation for putting looks like:

OK, let's back up a moment. Fearing and his colleagues Jason Acimovic and Stephen Graves wrote up that equation as part of a 2010 paper titled "How To Catch a Tiger: Understanding Putting Performance on the PGA Tour."

How did they figure out how putting works? The first step was to take the ShotLink data and figure out the probability of making a putt from five feet, 10 feet, and so on. Lots of researchers have done this (including the Brits in Search for a Perfect Swing), and the shape of the curve hasn't changed much over the years.

The closer you are to the hole, the more putts you make. These days, pros make 50 percent of their putts from eight feet and 20 percent of their putts from 16 feet. Then the curve flattens out: They make very few putts longer than 40 feet.

Next, the researchers looked at missed putts: How far does the ball stop from the hole? Getting the data to behave requires using "gamma regression," but the answer is what you'd expect: The longer the original putt, the longer the average distance of the subsequent stroke. With these two pieces of data, the MIT team had the foundation it needed to figure out a "putts-to-go" number for every point on a green.

So far, so good. But as golf buffs know, there are lots more variables to consider. Conventional wisdom holds that golfers who consistently land the ball downhill from the hole will leave themselves easier uphill putts. Wouldn't their great approach shots, then, give their putting stats an unnatural boost? Actually, the data shows that whether you are uphill or downhill from the hole is statistically insignificant. Fearing and Acimovic told me their most striking discovery was just how dominant a factor distance is when it comes to making putts. In their opinion, just two other factors have a significant impact.

The first is that elite golfers play the most prestigious tournaments, which typically have the fastest, most-difficult greens. The guys who qualify for the Masters, for example, usually see their putting rankings take a dip on account of Augusta's bewitching putting surfaces. On the other side, if you play a lot of courses with slow, level greens, you are going to look like a better putter than you are.

To correct for this bias, the MIT team adjusted its model. It figured out whether a particular green on a particular course was "easy" or "difficult" by looking at all of the putts taken on that green. But that presents an additional complication: A green could be "difficult" because the players in that tournament just weren't very good putters. Fearing and Co. thus also factored in the overall quality of the putting skill in the field. Once the computational dust settles, the model can distinguish between the value of sinking a putt from 12 feet on an "easy" green and the value of sinking a 12-foot putt on a "difficult" green.

The result, happily, is a list. The poster boy for the difference between MIT's putts-gained-per-round rankings and the standard stats is Ernie Els. From 2003 to 2008, the South African star ranked 15th in the PGA Tour's putting average. During that same period, he ranked 283rd in putts gained per round—his -0.63 mark means he gave back six-tenths of a stroke to the field each 18 holes with his substandard putting.

In this case, the putts gained per round stat matches what golf fans see with their eyes: Els is a wonderful iron player but a poor putter. The reason Els' putting average is so strong, the MIT team explains, is that—on account of his great iron shots—his "first putt" distance is two feet shorter than the average pro. Putts gained per round strips away those approach shots and reveals the truth: Ernie Els is an elite player despite his putting, not because of it.

The MIT study also confirms a fact that, until this year, was a given in golf statistics: the ridiculous dominance of Tiger Woods. From 2003 to 2008, he ranked first in both putting average and putts gained, bettering the field by seven-tenths of a stroke per round with his putting alone. To put that in perspective, if Tiger was paired with Ernie Els, Ernie would give up almost a stroke and a half to Tiger on the greens.

But the real star here is the putts-gained-per-round model. It has great flexibility, allowing us to evaluate a golfer's aptitude on the greens over a career, a year, or a tournament. It can also tell us, in real time, Tiger's expected putts to go from the back of the 17th green. Putts gained per round, then, will be the best possible test case for the new golf statistics: If it doesn't catch on with fans and players, nothing will.

The latest research has also revealed that putting is less important than it's made out to be. Ryan Moore, it turns out, is wrong about the key to winning on the PGA Tour—it doesn't really all come down to putting. In my next piece, I'll explain why the line "Drive for show, putt for dough" doesn't hold up to statistical scrutiny. A more accurate take on the old cliché: "Drive for dough, putt at least so-so."

Dead Solid Lucky: Does winning a golf tournament come down to skill or chance?

There's a longstanding faction in golf that thinks putting has too much influence on a golfer's scorecard. Here's Ben Hogan: "Hitting a golf ball and putting have nothing in common. They're two different games. You work all your life to perfect a repeating swing that will get you to the greens, and then you have to try to do something that is totally unrelated." Hogan is joined by Gary Player, Chi Chi Rodriguez, and Johnny Miller, who have all declared at one time that putting is unmanly, unfair, and "not golf."

Even the gracious golf writer Herbert Warren Wind brooded over the dominance of putting. Here he is writing in Golf Digest in 1972: "Over 18 holes, even the best player in the world can lose to a man with a hot putter, and it is rough for a star's self-esteem to be beaten in a head-to-head encounter by his peers, let alone by some upstart bumpkin."

It's easy to understand the chokehold that putting has on the golfing mind. If you flub a drive or fly the green with a 9-iron, there's still hope that you can make up for it with a miraculous recovery shot. In contrast, putting delivers a brutal, obvious, and seemingly final judgment. You miss the eight-footer, you drop a stroke. It's no wonder that Ryan Moore and many of his peers see putting as the skill from which all good things in golf flow.

But does putting really have an outsize impact on the game of golf? After the MIT team established its putting rankings, it calculated which golfers pick up the most strokes off the green. The top five names may be familiar to you: Tiger Woods, Vijay Singh, Jim Furyk, Phil Mickelson, and Ernie Els. No "upstart bumpkins" to be found.

The authors underline the starkness of these results: "All the top 20 golfers are better than average off-green performers, while roughly a third are worse than average putters." Three-time major champion Singh, for example, drops one-third of a stroke per round with his putting but gains 2.3 strokes with his other shots. While it certainly wouldn't hurt Singh to perform better on the greens, his superior shot-making more than makes up for any weakness with the putter. The opposite scenario doesn't hold: Great putting will never make up for not being able to consistently crush the ball into the horizon. A golfer's power also gives his long-iron shots a higher trajectory, allowing him to land the ball more softly on the greens, which in turn allows for greater accuracy.

Pro golfers who lack adequate power are like runners competing with pebbles in their shoes. They lose fractions of a stroke on most long shots, meaning that over 18 holes they are slowly ground down by the course. Golfers overemphasize putting because they can't mentally tally these fractional losses. Instead, they carry around those pesky missed eight-footers. But the truth is that once a pro golfer is crouched down to examine the break of a green, there's not as much room for him to excel. That's partly because golfers are very close in skill on the greens, and it's also because nothing that disastrous can happen, such as putting into the water. The tee box, the fairway, and the rough are where good and bad things happen on the golf course. The green is mostly there to make you hate yourself.

We also have to be careful not to err in the opposite direction and declare that the long game explains everything. All the data show that winning on the PGA Tour requires a player to have a career week, to perform better than average in several different facets of the game. In fact, winning may be even scarier than that: It may be beyond a golfer's control. A team of researchers has found that triumphing on tour almost always comes down to luck.

At this year's Masters, Phil Mickelson provided stunning demonstrations of both luck and skill. On the second hole on Sunday, Phil had what looked like an easy birdie putt:

A seed falling into the path of your putt during your backswing—doesn't get any more unlucky than that. Then there is "The Perfect Shot," a 6-iron that Phil hit around a tree on the 13th hole while nursing a one-stroke lead:

Two business-school professors, Robert A. Connolly and Richard J. Rendleman Jr., have done the most work on luck vs. skill in golf. Connolly and Rendleman collected data (PDF) from all stroke-play PGA events between 1998 and 2001, then used something called a "smoothing spline" model to tease out which portions of a player's score could be attributed to skill and which to luck.

"Luck" can arrive in many fashions. A tournament may be held at a course with a setup that favors a particular player. (Connolly and Rendleman found that this "player-course" effect was present but modest.) Next, a player might get lucky with the weather. That happened this year at the British Open at St. Andrew's when the winds became wicked on Friday afternoon, seeming to ruin the chances of golfers with late tee times. It turns out that getting caught in a "bad rotation" on the course does have a real impact. In some tournaments, this effect came out to just half a stroke, but in competitions that were marred by extreme weather, the rain and wind cost unlucky golfers as many as five strokes.

Then there is the luck that we think of as luck: the approach shot that hits a rock (dang!) and ricochets onto the green or the ball that gets knocked into the hole by another player's shot (yes!). Or, more commonly, the forgiving bounce in the fairway, the putt that takes a victory lap and falls in—and the bad lie in the fairway, the shot that skips off the cart path into the water, etc.

This kind of luck cannot be directly measured. What Connolly and Rendleman do is model what a player is expected to shoot, accounting for their recent play, the course, and the weather. They then declare any deviation from that expected score attributable to "luck."

How big a deal is luck on the golf course? On average, tournament winners are the beneficiaries of 9.6 strokes of good luck. Tiger Woods' superior putting, you'll recall, gives him a three-stroke advantage per tournament. Good luck is potentially three times more important. When Connolly and Rendleman looked at the tournament results, they found that (with extremely few exceptions) the top 20 finishers benefitted from some degree of luck. They played better than predicted. So, in order for a golfer to win, he has to both play well and get lucky.

The "luckiest" performance recorded in the paper was turned in by Mark Calcavecchia at the 2001 Phoenix Open: 21.59 strokes. If you revisit that victory, it makes sense. At the time, Calcavecchia had turned 40 and was in a deep slump. That week, against a strong field that included Tiger Woods, Calc equaled the tour record for birdies, with 32, and tied another tour record by finishing 28 strokes under par.

Of the tournaments that Connolly and Rendleman analyzed, only one win could not be attributed to some degree of luck: Tiger Woods' victory in the 1999 Walt Disney World Resort Classic. While the absence of "luck" is less easily observed than its presence, I can make some guesses about what happened here. This tournament was marked by lightning-fast greens and holes that were cut into the slopes (making the putting even trickier). Woods missed five putts from inside 10 feet and three-putted three times. It seems that everyone else played worse, though. During the final round, Tiger's closest pursuers fell apart: Ernie Els hit into the water and putted off the green, and Bob Tway collapsed after a triple-bogey. In this instance, Tiger's high standard of play allowed him to "hang in there" while everyone fell back.

Connolly and Rendleman conclude that only the very best golfers of the late 1990s and early 2000s—Woods, Mickelson, David Duval, Davis Love III—were able to win a tournament without being significantly luckier than the rest of the field. The average player needs a lot of shots to go right for him—and, typically, a lot of shots to go wrong for everyone else—in order to hoist a trophy on Sunday. Think about that when someone you've never heard of—Graeme McDowell, Louis Oosthuizen—wins a major championship.

On the surface, these findings can be dispiriting: It all comes down to the golf gods? Why even bother?

That's not really the point. The "luck" that Connolly and Rendleman quantify doesn't affect how the game is played, only how we understand it after the fact. These researchers also can help reclaim greatness for players who've been blamed for failing to come through in the clutch. Until he won the Masters in 2004, Phil Mickelson was pilloried for choking in the majors. But according to the Connolly-Rendleman analysis, Phil actually played better than expected in these big tournaments. He just wasn't as lucky as the guys who eventually won. He played well. They played out of their minds.

Golf is a psychological kick in the teeth: Like Phil Mickelson, you can bring your best golf to a major and still lose. A golfer can deal with this fact in one of two ways. The first option is to let go and accept your fate—to be the reed bending in the wind. The other choice is to do everything in your power to fine-tune the aspects of the game that you can control. Golfers are, of course, obsessed with their swings. But what about their strategy? That's a part of the game that's within their power, but often neglected. In my last piece, I'll look at how pro golfers approach stats and whether sifting through the numbers can save them strokes on the course.

Why You Aren't a Pro Golfer: A video slide show.

"What an incredible Cinderella story! This unknown comes out of nowhere … to lead the pack … at Augusta. He's on his final hole. … He's about 455 yards away. … He's gonna hit about a 2-iron, I think." So begins the legend of Carl Spackler, and the finest improvised golf monologue in cinematic history. Not to be too literal-minded about a riff from Caddyshack—but why couldn't a former greenskeeper win the Masters?

One of the many ways that golf boggles the mind is how you can be both so bad at it and so good. Golf will allow moments of grace, like the 5-iron that rolls to two feet or the 40-foot putt that finds the cup. For that brief, shining moment, you hit a shot as well as a human being possibly could. You will never wrongfoot an NBA defender, you will never turn on a 95 mph fastball—but on the golf course, you can occasionally equal the best in the game. Right?

Actually, no. Golf researcher Mark Broadie has a database full of amateur shots: the drives we shank, the 9-irons that go sideways. He compared the amateur game with the pro game. The results were instructive, but they were not pretty.

Let's take a video tour.

Zen Golf vs. Moneygolf: Should the pros pay attention to statistics?

This isn't the first time that a new technology has descended upon golf, promising to change the game. In To the Linksland, * Michael Bamberger's 1992 book about caddying on the European tour, there's a passage in which Bamberger seeks the counsel of a wizened Scottish pro named John Stark. Here's the short version of their first encounter:

"Tell me what it is you seek to accomplish," John Stark said.

"I want to get better," I said quietly.

"You want to get better, a worthy goal," Stark said. "But what makes you think tuition is the way to improvement? I've seen many players ruined with instruction. I've seen instruction rob a player of all his natural instincts for the game."

Stark then begins a long monologue in which he dismisses American players as "outstanding golf robots" and argues that the fad for high-speed photography of golf swings corrupted the game in the 1950s: "It all seemed so obvious: there was a correct position for everything, all the points in the swing." But that was a false path. The game became too "technical" and the players lost their way.

In golf, there have always been those who side with "instincts" and those who side with analysis. I love the stories about 1920s professional golfer George Duncan, who would swing at his ball as soon as he reached it. He considered practice strokes tantamount to cheating. (Those early pros would also be amazed at how today's top players stalk the green for days to line up a putt.) In our time, the most instinctual golfer would be putting enthusiast Ryan Moore, who, at times, will disdain even to consult a yardage book.

When I talked to players on the PGA Tour—the alleged "golf robots"—I was surprised by how skittish they were about stats. Players certainly understand the importance of gaining a fractional advantage on the competition. When Phil Mickelson approached short-game guru Dave Pelz for help in 2003, Pelz was surprised that the game's pre-eminent player from short range would need his help. Mickelson's answer: "I want to be a quarter of a shot better per round in the majors." Most golfers don't seem to believe, though, that scrutinizing stats will get them the fractional gains they crave.

In my conversations with golfers, I would get a lot of staring at the ground once the word "ShotLink" came out of my mouth—as though I had mentioned Voldemort in the land of Harry Potter. Industrious pro Michael Letzig spoke for many of his peers when he said he never looks at his numbers during the season: "The stat is not going to change my swing." Letzig also had a touch of John Stark in him, telling me: "What's different from the people inside the ropes and the people outside the ropes is that, in here, golf is easier because we keep it simple." (True enough, Michael—though it's easier to keep it simple if you have transcendental talent.)

Several pros told me, in so many polite words, that they don't need a laser beam to tell them how far they hit their 5-iron. They play golf every day. How could they possibly be ignorant about their game? They can see what they need to do with their eyes.

This is the same prejudice that Bill James crusaded against in baseball—that the numbers can tell you what your lying eyes refuse to see. A golf game is actually hard to analyze. While I doubt most pros can recall their last 100 drives, ShotLink remembers them all. And you need to look at 100—or 200 or 500—drives to see whether you're losing fractions of a stroke. You don't even have to know the new stats I've been discussing to acquire useful insights. Golf consultant Mark Sweeney helps break down the ShotLink numbers for his pro clients. He told me of a player who, it was clear from the stats, was deficient with his 8-iron. All of his other iron play was good; the numbers revealed a blind spot.

I talked to a few players who had more favorable things to say about ShotLink. Brian Davis, an Englishman currently ranked 41st on the PGA Tour's money list, was the savviest pro I ran across. Davis says he looks at ShotLink every week and does a more in-depth analysis at the end of the season. He knows from ShotLink that he's lacking compared with others in driving distance, so he tries to "ramp it up" from the tee on holes where a long drive would clearly help. This is an ideal use of stats—a golfer using the numbers to fine-tune his strategy. He takes the risk of trying to really smoke a drive (and potentially end up in deep trouble) because the stats tell him he needs that distance to keep pace.

Davis also recognized that ShotLink has its limits: "You still need to play the game of golf." While it's nice to hit the green, "Sometimes you need to play away from the flag, or leave it short." Davis gave another example: "If I know that if I go over the green I'm dead, I might not mind if it lands 10 feet short of the green and I can just putt it up there."

Part of playing a golf course like a pro is knowing where to miss. There are good and bad places to find your ball, a fact that is lost on ShotLink. The intricacies of shot placement are not lost, however, by the most innovative golf stats. That's because the new stats are based on distance and location. The MIT putting study, for example, can identify the places on the green that are the most treacherous.

So, let's speculate about what it would mean if players genuinely knew where they stood in terms of driving, putting, and all the other facets of the game. The first and probably greatest benefit would come from using "moneygolf" to practice efficiently. The tour is filled with guys who show up, shoot 72-72, miss the cut, and go home. If the stats help you gain a few strokes on the other players, you'll stick around to play four days, finish in the money, and survive on the PGA Tour another year.

The big caveat to the use-stats-to-hone-your-practices theory is that moneygolf demonstrates the importance of the long game, and it's unclear whether you can really teach power. Some golfers have an innate ability to generate tremendous clubhead speed. A golfer can certainly work on his strength and flexibility and tailor his equipment, but short hitters don't transform themselves into long hitters. Plus, you are fighting age.

A second significant benefit for stat-savvy players would come from what Brian Davis is already doing: using moneygolf to strategize. A shot-value analysis of a player's last few tournaments would give a snapshot of what's working and what isn't. While moneygolf won't fix a broken swing, it could help a golfer think about how to play a given hole based on the current state of his game. It could also provide a psychological boost: If your chipping has been solid, you can be more aggressive on the approach, knowing that you've been recovering well from misses.

But here I've already crossed the bridge from statistics into a player's mind. Those of us "outside the ropes" can use moneygolf to better understand the game we love, but the players don't have that luxury. They succeed or fail stroke by stroke, hole by hole—each shot is taken in a pressure situation, one that commands a player to focus and, in the parlance of our time, "execute."

As I've written this series, I've been haunted by the conversation that I had with former U.S. Open champion Jim Furyk. I cornered Furyk as he walked off the driving range, starting in with my usual ShotLink spiel. He started, like many players had, by talking about how greens in regulation is a bogus stat. Then he stopped and looked at me.

"I don't look at that stuff," he said. Then he paused and said, "I know."

Another pause.

I'm kind of slow on the uptake: "Uh, what do you know?"

Furyk was gracious: "I know in my heart what I did on the course that day. If I don't have confidence when standing over a shot, I know that I need to go out and work on it."

He then stepped into a golf cart and drove away.

To hear Michael Agger, Josh Levin, Mike Pesca, and Hanna Rosin discuss Agger's "Moneygolf" series, click the arrow on the audio player below and fast-forward to the 16:35 mark:

You can also download the podcast, or you can subscribe to the weekly Hang Up and Listen podcast feed in iTunes.