A Dangerous Game

The devastating repercussions of lifelong football head injuries.

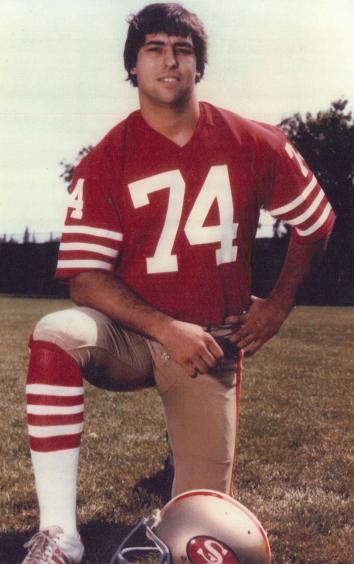

I grew up in a football family, the fifth of six kids, with both of my older brothers playing football through college. My dream from when I was very young was not only to be better than my brothers, but also to be the greatest NFL player of all time. These were big dreams for a 106-pound, very skinny, very slow 11-year-old playing his first year of Pee Wee Pop Warner in 1970. I was so knock-kneed that the coaches nicknamed me “Clang” for the noise they said my knees made when I ran. Despite my physical attributes, or lack thereof, from my first day in pads I loved the game. I had no doubts I'd make it in the NFL.

During my third year of Pop Warner, I knocked myself out during a Bull-In-The-Ring drill and was hospitalized. With 40 kids on the team, the drill entailed being assigned to a numbered pair who would oppose each other. When your number was called, you and another player rushed to the ball at the center of the ring, fighting to get the ball back across your line. Anything went; you could tackle the guy and drag him by a leg, rip the ball loose, any way you could get the ball back. Each time you got the ball across the line your team got a point, and losers ran an extra five sprints after practice.

This drill did absolutely nothing to make us better football players. It was a gladiator drill for the coach’s amusement. Youth coaches with limited credentials and big egos forced young players in potentially life-altering situations. Frankly, they’re the last people in the world that parents should entrust with their children's health.

When Coach called my number during that Bull-In-The-Ring in 1973, I was opposite our fullback. I had about five pounds on my opponent, and was tipping the scales at a robust 131 pounds. Though I was already over 6' tall on my way to my present 6' 5”, I was so skinny I barely cast a shadow. In this instance, I wasn't concerned about the ball and I decided to just go for a kill shot. We hit top of helmet to top of helmet, full speed from 25 yards apart. After we collided, I lay face down in the grass for a few moments not moving. My opponent was down next to me on his back moaning. He slowly rolled over on all fours, staggered to his feet, picked up the ball, and groggily stumbled across the line for a point.

A moment later when one of the coaches approached me, I struggled to my feet, took one-step sideways and fell face first in the grass. One of the parents watching practice took me to the emergency room.

My old man was summoned and took me home from the hospital a couple of hours later. When I got home, my family was watching the Jackie Gleason Show. As they watched, about every 90 seconds I'd continually blurt out with, “Hey, what are we watching?” Nothing was sticking. Information that entered my brain just poured out each ear like water in a leaky bucket.

After that first diagnosed concussion in 1973, I was held out from play for just three weeks then returned for the rest of the season. On my first day back at practice they had us running Bull-In-The-Ring again. One of the coaches approached me as we lined up and said, “Don't be afraid to hit now. The best thing for you to do is to get back out there and knock the snot out of someone.”

Who is this game for? The kids? I don't think so. How many 9- and 10-year-olds need to be toughened up by smashing their brains into one another? We need to recognize and take actions against coaches conducting dangerous practices.

I went on to play several games in high school, college and pros, where I never even remembered playing the game. Yet I was never diagnosed with a concussion, and I never missed a play or practice.

Studies have also shown that the younger you are when first concussed, the lower your threshold is for the next. And it doesn't take concussions to cause brain damage. The brain is encased in a hard skull, with sharp boney ridges on the inside, and is surrounded by cerebral spinal fluid. Each of the thousands of sub-concussive hits an average high school player takes each season causes the brain to slosh around in the skull. Sometimes it hits the front of the skull and bounces back and hits the back of the skull. They call this a coup contrecoup injury, where the neurons get stretched. Neurons are partially composed of a stabilizing protein called tau protein and as the neurons get stretched repeatedly they get inflamed. The inflammation increases over time and over time the neurons begin to die. As they die, the sticky tau proteins disengage from the tubules and form amyloid plaques, which clump together and may block cell-to-cell signaling at synapses. This build up of amyloid plaques is a precursor to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE.

One of the problems with head injuries in younger players is that your brain continues to develop into your twenties. Damage to a developing brain can worsen over the long term, leading to devastating effects in adulthood. Four years ago at age 52, doctors prescribed Lexapro to me for memory problems, in addition to the Lamictil, the anti-seizure medicine I'd been on for decades. Lexapro didn't seem to help, so they stacked Arricept and Nameda, both dementia medicines, on top of those two.

Since my youth, I've lived with the repercussions of not taking football head injuries seriously. I was 22 when I had my first of what are now nine and counting football-caused emergency VP Shunt brain surgeries, and my football injuries have impacted not only my life, but have torn my family apart. In addition to football-caused gran-mal seizures, short-term memory problems have arisen from damage to my temporal lobes and anger management issues and poor judgment due to damage to my frontal lobe. My array of physical and psychological symptoms contributed to the loss of my environmental consulting business in 2011, my family's home in 2012, and my 20-year marriage to the mother of my three children in 2014.

Early in the following 1981 Super Bowl season, a few weeks after my first knee surgery, I was having daily symptoms of vomiting, hearing and eyesight loss, debilitating headaches, and the paralysis of my right arm. I was misdiagnosed as having high blood pressure and I was put on diuretics.

My symptoms worsened, and after two weeks on diuretics a team doctor recognized that I had a brain hemorrhage. I drove myself to Stanford Hospital, underwent a CT brain scan that evening, and was taken in for emergency VP Shunt brain surgery. I had developed hydrocephalus. The doctors drilled a hole in my skull and inserted a drain tube into the ventricles in the middle of my brain. The drain tube runs to a pressure valve (shunt) that was installed in the back of my head, behind my right ear. From there they plumbed it down the side of my neck, through my pectoral muscle and into my abdomen to permanently drain spinal fluid from my brain. The shunt has since failed eight times; each time I go into a coma and will die unless operated on shortly after. If a hospital isn’t available and the shunt is clogged, I have to resort to an emergency “brain drain kit” which I carry around, made up of a razor, antiseptic gauze, needle, surgical tubing, and a large syringe.

I’m not anti-football, despite my nine NFL-caused emergency VP shunt brain surgeries and 33 years of gran mal seizures. I coached and taught at the high school level for several years. The closest friends I have in the world are some of my old college teammates from nearly 40 years ago. I played on Pee Wee Pop Warner and Pop Warner championship teams, an undefeated, nationally ranked high school team in 1975, in the 1977 Orange Bowl with Colorado and on the 1981 SF 49ers Super Bowl championship team.

What I am against is unnecessary, life-altering traumatic brain injuries, especially those that can be avoided. A traumatic brain injury is a slow-progressing, insidious disease that robs you of who you are and destroys families. It's an injury to the most important organ in your body, an organ that defines who you are. Are any of the so-called character building values a young child learns from playing a game worth who they are as a person?

As my memory problems worsened, it got harder and harder to continue running my environmental consulting business. But my drive to help those with traumatic brain injuries grew as I read about more and more of my NFL brothers who were suffering the same fate as my family. I dove into learning as much as I could about traumatic brain injuries, and coupled with my own knowledge and expertise I had acquired over the prior 30 years, I founded The Visger Group – Traumatic Brain Injury Consulting. TBI Consulting is one thing I can do with very little short-term memory.

The Visger Group is associated with some of the top experts in the world in TBI diagnoses, treatment and recovery. We bring in doctors, experts and former NFL players to present at some of our Coaches Concussion Clinics, and I coordinate directly with Dr. Richard Ellenbogen, co-chair of the NFL's Head, Neck and Spine Injury Group. Dr. Ellenbogen approached me in 2010 for suggested rule changes to reduce TBIs in football when he first came on board. We have presented seminars on Traumatic Brain Injury Recovery and Coping Mechanisms. We also conduct Coaches Concussion Clinics and are dedicated to coaching coaches on taking the head out of the game without losing the integrity of the game.

The NFL has implemented many of our recommendations since 2010, yet when I look at youth football today, it takes me back to the 70's when I first began playing. Coaches of our youngest players should be schooled on brain injuries more than at any other level. Our youngest players are the most vulnerable, yet are subjected to the most damaging drills.

There is a reason you don't see Bull-In-The-Ring drills in the NFL. How many youth football parents and coaches would like to see their kids and players in my shoes, forced to carry around an emergency brain drain kit?

Is it really only a game?

Anyone looking for help or resources pertaining to TBI can go to our website at:

The Visger Group www.thevisgergroup.org

To explore more on the debate about youth football click here.