The Stunt Presidency

Donald Trump plans to replace governing with gimmickry. It’s already working.

Chris Bergin/Reuters

Chris Bergin/Reuters

Last week in Indiana, Donald Trump saved a thousand jobs. You heard the story: Carrier, a heating and cooling company, had been planning to move some of its operations to Mexico. Then the president-elect personally phoned the CEO of its parent company. Then Carrier announced that it would accept tax incentives from the state of Indiana in exchange for keeping some of the jobs—between 800 and 1,100 of them, depending on who you ask—in the USA.

There are many reasons to be skeptical of this achievement. Bernie Sanders complained about the 1,000-plus jobs still moving to Mexico, and about the example the deal set: Trump “has signaled to every corporation in America that they can threaten to offshore jobs in exchange for business-friendly tax benefits and incentives.” At a White House briefing, Obama Press Secretary Josh Earnest noted that a thousand jobs is peanuts compared with the more than 1 million saved by Obama’s auto bailout or the 805,000 manufacturing jobs created during his term. Larry Summers expressed concern that Trump’s use of personal leverage and implicit threat could lead American capitalism away from the rule of law. (The tax breaks Carrier accepted did not nearly cover the anticipated savings of the Mexico move, but Carrier’s parent company, in which Trump held an investment as recently as 2014, relies on federal contracts for a nice chunk of its revenue, which may have incentivized it to stay in the president-elect’s good graces.) The Wall Street Journal editorial board sounded a similar alarm, noting that “Mr. Trump’s Carrier squeeze might even cost more U.S. jobs if it makes CEOs more reluctant to build plants in the U.S. because it would be politically difficult to close them.” Even Sarah Palin, that noted voice of reason, called the deal irrational: “When government steps in arbitrarily with individual subsidies, favoring one business over others, it sets inconsistent, unfair, illogical precedent.”

All of these complaints have merit. Unfortunately, none of them matters. The Carrier deal is a triumph for Donald Trump, and it’s one that should terrify those concerned about what his presidency might bring (and how long it may last). The incident shows how keenly Trump understands the power of a concrete example. The Carrier deal will be good for the workers whose jobs will stay in Indiana, yes, but it functions primarily as a stunt that expertly reinforces Trump’s brand. As a candidate, he promised to use his deal-making skills to improve the lot of the American worker. Now, nearly two months before he even takes the oath of office, he has delivered. No matter what happens on Trump’s watch—to Carrier, to the manufacturing sector, to employment numbers overall—there will be some set of voters, and not just Trump fans, who vividly remember this moment, thanks to its clarity, to its tangibility. Each critique of the Carrier deal requires the listener to hold in his or her head several levels of abstraction: ideas about how systems and incentives work, ideas about cause and effect, ideas about how corruption can unfurl or how policy can affect millions of people. And so each critique has less impact than the sturdy story: Last week in Indiana, Donald Trump saved a thousand jobs.

Hector Mata/AFP/Getty Images

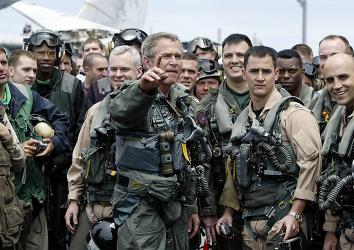

Of course, politicians have long used stunts and stories to connect with voters. The stunts have typically been press opportunities meant to shape our perceptions of a candidate or leader. During the 1988 campaign, Michael Dukakis and his press secretary contrived to toss a baseball around on a piece of San Diego tarmac for an audience of 40 journalists, successfully pantomiming masculine regular-guyness for the press. (Tales of the Duke’s penchant for a good old-fashioned catch made it into more than one campaign dispatch.) When George W. Bush donned a flight suit for his visit to an aircraft carrier and then stood under that “Mission Accomplished” banner, the effect was to create a concrete vision of a commander putting a war successfully to bed. And it was Reagan, that master storyteller, who began the State of the Union practice of packing the balcony with anecdotes: Trevor, who helps the homeless, or Cindy, a teacher in a new program called AmeriCorps, or Josefina, whose life will be made better by tax cuts. In these cases, the representative human is customarily trotted out as an example. I’ve enacted a new policy, the politician says. Look how well it’s working for Joe. The idea is to take the abstract work of governing and make its effects real for the citizens watching at home.

Trump is up to something different. The jobs saved at Carrier aren’t examples of a proposed plan that promises similar, widespread results for the American workforce. The jobs saved at Carrier are the plan. Trump used his power as president-elect to intervene on behalf of a small group of individual Americans and claim victory. The resulting anecdote is the policy. The resulting press opportunity is the policy. The approach collapses any distinction between the work of leadership and the promotion of that work. It bypasses the abstractions of administration and substitutes visceral image-making instead. What Trump has laid out here is a troubling blueprint for government by stunt.

To understand how fiendishly effective this tactic might be, it’s worth considering the facsimile of “business” presented on Trump’s reality show. The Apprentice series premiere gathered a group of MBAs, copier salesmen, and leggy stockbrokers, split these contestants into two teams (men vs. women), and asked them to run competing lemonade stands on the streets of New York City. The results make good television. At one point Trump is shown in a helicopter, surveying the streets below and complaining about the male team’s smelly location by the Fulton Fish Market. The women use their sex appeal to move the product, doling out cheek-kisses and phone numbers along with paper cups of lukewarm liquid. At the end of the day the women win, and one of the guys from the men’s team (an overeducated Ted Cruz-ian doofus with bad people skills) is sent home.

What’s striking about the show, though, is not how phony it seems but how masterfully it presents its version of “business” as real. In many Apprentice challenges, the teams are judged by how much money they earned—a seemingly irrefutable criterion, especially when compared with the squishy aesthetic and personal judgments that prevail on shows like Project Runway, the Bachelor, or Dancing With the Stars (although of course it’s not clear who’s auditing the books). In the premiere Trump explains that the winner will get to work for his organization as “the president of one of my companies,” a role that seems startlingly significant for a reality-show prize and gives the proceedings more heft. The viewer comes away with the idea that running a company entails performing well at a set of random, atomized, concrete tasks. Turn an empty storefront into a pop-up bridal boutique. Develop a new menu item for a chicken chain. Run a profitable pedicab operation for an afternoon. Do these things, and voila—you’re C-suite material.

The Carrier deal is the first hint that Trump may approach “governance” the way his show approached “business”: as a set of small, tangible wins to be stacked up week by week. The approach is opportunistic rather than strategic, concerned with short-term victories rather than the unglamorous work of building something enduring and strong, anticipating and minimizing unintended consequences, understanding historical imperatives, and assessing the potential levers that can effect systemic change.

Trump, of course, might argue that he knows the difference between business and “business,” and that he’ll get to the policy stuff once he’s ensconced in office. Just this weekend he tweeted that Americans can anticipate a 35 percent tax on goods imported by companies that outsource jobs, a plan that, whatever you think of its mercantilist merits and whatever its chances of getting through Congress, would at least be a policy applicable to all. Still, when George Stephanopoulos asked Mike Pence on ABC’s This Week whether hounding individual CEOs would be an ongoing part of Trump’s strategy, Pence said the president would make those decisions “on a day-by-day basis.”

No matter how engaged with policy Trump turns out to be, his 12 years of presenting business acumen as a series of memorable stunts will have a deep impact on the way he governs us. He’ll serve up his own presidential prowess with similar élan. Trump’s whole campaign testified to his knack for making America’s troubles seem tangible for voters—vivid, simplistic challenges to which he offered vivid, simplistic solutions. The challenge is ISIS; the solution is bombs. The challenge is murderous, marauding immigrants; the solution is a wall. The challenge is a self-dealing Washington political elite; the solution is jail for Hillary. It’s almost as though he sees the problems facing the country in episodic narrative form.

The challenge then for journalists is to become more than tart recappers of this unfolding show. Which will be more difficult than simply deciding to do so. As much as journalists decry Trump, he’s awfully good at giving the media exactly what it actually wants. He offers drama and conflict. He stirs emotions. He skips the policy crap and offers up compelling anecdotes all on his own, saving everyone the trouble of finding them for themselves. If journalists choose to ignore these easy narratives, they will stand uncontested, because Trump can deliver them to voters on his own. Journalists must instead set out to challenge these stories—by, say, following Carrier and its employees over the next four years, or by examining how the federal contracts for parent company United Technology Corp. do or don’t change, or by tracking the fortunes of other companies in the field—but as they do they’ll still be directing attention at the tidy diorama Donald Trump has put forth.

Trump’s instinct for the visceral also arrives at a moment when journalism has trended toward the abstract. The rise of data journalism over the past decade—as a practice and a set of instincts—means that many journalists spent much of the campaign operating well above sea level, examining systems and patterns in the expanse of available facts: the economic indicators, the demographic trends, the polls. It’s become journalistic custom during this period to sneer at the isolated anecdote: the yard signs in a particular neighborhood, or the sizes of particular crowds, or what one woman in a swing-state diner said. These critiques of anecdotal information can feel thin these days, given how convenient they are for newsrooms that can’t afford to spend much money on reporting, and how fallible some data-driven campaign analysis turned out to be. But the journalistic trend away from overreliance on anecdote remains fundamentally sound. It’s essential to gather new information from diverse sources, always. But no single detail can reveal the whole picture, and it’s the synthesis of complex and varied information that delivers true understanding.

Nevertheless, Hillary Clinton’s campaign, after lingering long on Clinton’s policy chops, eventually settled on the approach of countering anecdote with anecdote. They presented the stories of maligned former Miss Universe Alicia Machado and, more effectively, bereaved gold star father Khizr Kahn, whose story of loss and insult seemed to carry more weight with some voters than the great newspaper excavations of Trump’s chicanery with his taxes and foundation. These attacks stuck because they framed the problems with Trump as sharply as Trump had framed the problems with America, and in both instances Trump was left fumbling for a response. The question is whether a press corps with strong instincts for analytic abstraction is best suited to a president who governs by anecdote.

On Friday, after the Carrier hosannas had died down, Donald Trump put another company in his sights. “Rexnord of Indiana”—a business that makes industrial components—“is moving to Mexico and rather viciously firing all of its 300 workers,” Trump tweeted. “This is happening all over our country. No more!” Last week in Indiana, Donald Trump saved a thousand jobs. Next week maybe he’ll save a few hundred more.