JACKSON, Mississippi—On the drive in, it’s easy to miss the trailer that Tara Kelly shares with her husband, Clayton. Two cars, one of them busted, are parked in a short driveway. A patio is happily cluttered with the toys and bikes of the couple’s autistic daughter. The only indication that a political activist lives here is a sign for Senate candidate Chris McDaniel, shoved mostly out of sight, under some stairs.

“Yeah, we’re sort of trying to get that out of the way,” Tara Kelly says, referring to the campaign sign as she invites me to sit on the porch. She’s just returned from her regular 30-minute visit with Clayton, who’s in prison on a $200,000 bond. (He will only be freed on Thursday, after the bond is reduced.) Ten days earlier he was arrested for allegedly gaining access to the nursing home where Sen. Thad Cochran’s wife lies bedridden with dementia, and taking video of what he saw. The video briefly appeared on his YouTube account, Constitutional Clayton, before McDaniel’s campaign asked (via an email to other activists) that it be taken down.

“I told him not to do it,” says Tara Kelly. “I wouldn’t want anyone taking a picture of me in a hospital! But he really wanted to get his name out there as a journalist. And he has gotten his name out there. Just not the way he expected. He thought he was getting the scoop.”

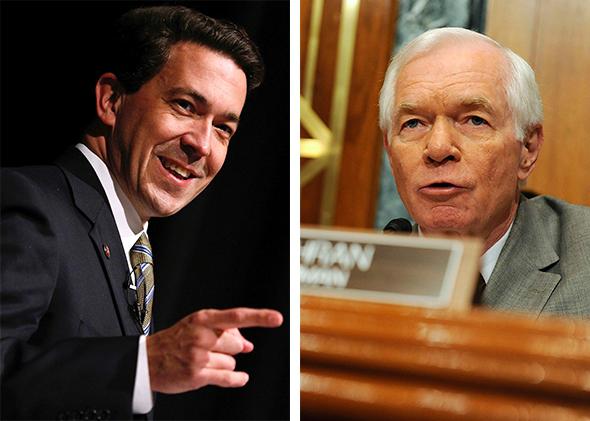

Instead, Clayton Kelly made a decision that roiled the year’s tightest race between an incumbent Republican and an avatar of the Tea Party. McDaniel, a state senator and former talk show host, entered the race in October 2013, after the Club for Growth had already gone on the air trashing Cochran, and after he’d huddled with conservative PACs that wanted fresh Republican-In-Name-Only scalps. He outraised and outcampaigned a senator who’d won his first congressional campaign a few months after McDaniel was born. The first polling on the race gave Cochran a single-digit lead; the last poll, paid for by one of the many McDaniel-endorsing conservative groups, gives a slight edge to the challenger.

That poll was taken after the Cochran campaign and media outlets from Mother Jones to the Wall Street Journal “vetted” McDaniel. The candidate had endured weeks of stories about his radio days, and Republican primary voters did not clutch their pearls and flee after they learned McDaniel had criticized rap culture.

The only problem: The poll was also taken before the arrest of Constitutional Clayton. It was also taken before police charged three more activists, one of them the vice chairman of the Mississippi Tea Party, Mark Mayfield.

“He didn’t even know them when he was sitting in the same cell as them,” says Tara Kelly. “My personal opinion is they were just using him as the fall guy. He didn’t know them other than over Facebook.”

And the poll was definitely taken before Cochran’s campaign put out an ad that splayed Clayton Kelly’s face across TV screens, called him (correctly) “a Chris McDaniel supporter charged with a felony,” and asked voters to rise up and say no to dirty politics.

“Aren’t they exploiting his picture as well?” asks Tara Kelly. “That’s what I think, but that’s just my opinion as his wife.”

The race will be decided, by people who don’t know any of these activists, don’t know or want to know what happened at the nursing home, and don’t know why the whole imbroglio began. Why was Cochran a target in the first place? On Tuesday, after talking to Kelly, I stop by the biweekly meeting of the Central Mississippi Tea Party, where there’ll be a lecture on Obamacare and a huddle about how to beat the senator.

“One way to measure how successful we are is by securing votes for our candidate,” says Janis Lane, the president of the group. “Chris McDaniel is the man of the hour. He is chosen for a time such as this. He is our current-day Esther. He is what we need in Mississippi to make a change in the political process of this state.”

What “process” is that? Lane explains, without getting into specifics, that an accused child molester is currently being held on a $50,000 bond. Twenty-odd activists murmur at that—they do not need to be told that several of their awkward political allies are being held for much more. Lane refers obliquely to McDaniel’s “willingness to put himself and his family in this situation,” and at how the Tea Party has had “some challenges thrown in our way, and some obstacles.”

After the meeting ends, the activists hang back to explain. “About three weeks ago, we knew there’d be an ‘October surprise,’ ” says Don Hartness, a veteran who often stands at the side of a road in Jackson waving an American flag and raising money for the wounded. “We just didn’t know what it was going to be. Mark [Mayfield] is a personal friend, and this is just so out of character for him.”

And the whole story has let Cochran slide. According to Tea Party activists, Cochran’s alleged conservatism is not backed up by his votes. Any Republican who voted to fund Obamacare in last year’s continuing resolution—which, in Washington, was seen as the inevitable outcome after a disastrous conservative feint—is suspect.

“When I watch TV,” says businesswoman Kay Allen, who’s wearing only red, white, and blue, “whether it’s Fox or whoever I watch, I watch for which people are stepping out and putting bills on the floor and saying what they believe. People like Rep. Jason Chaffetz, Sen. Kelly Ayotte, Sen. Ted Cruz, Rep. Trey Gowdy.”

The next morning I drive north to the town of Grenada. McDaniel is traveling far outside his base, through northern Mississippi, into the towns that border Tennessee. An 8 a.m. rally is scheduled in the town square, which is marked by a monument to Confederate veterans and anchored by a white gazebo.

McDaniel’s bus, wrapped with his campaign logo and a king-size picture of the Constitution, rolls past the gazebo and into a nearby lot. The rally is downsized to a meet-and-greet. After the crowd has gathered, McDaniel strolls out of the bus in shirtsleeves and slacks to thank everyone for “braving the rain.” He praises a retired firefighter (“a heck of a service, isn’t it?”) and is thrilled by a Navy veteran who retired after 40 years.

“It was time to do something else,” says the veteran.

“Just like the Senate, huh?” says McDaniel.

Time for the speech—the short version. “The conservative movement needs revival,” McDaniel says. “It needs resurgence. This is the fertile ground. This is the place to begin this fight, to finally draw a line in the sand, and to win, once and for all.”

McDaniel says he’ll link arms with the senators who thrill the Tea Party. “If you’ve heard of Mike Lee, if you’ve heard of Ted Cruz, these people have been pushing this agenda for a long time,” he explains. The agenda is simple: term limits, tax reform, saying no to anything liberal, ending handouts to corporations.

“We’re watching the lower class suffer and the middle class suffer while others receive disproportionate benefits from the state and the federal government,” he says. “Our people have been poor for too long. It’s time to make some changes.”

The candidate concludes with a cheeky “trivia question”—how many people can name a circumstance in which Cochran “led the fight” against Barack Obama? It’s meant to be unanswerable, and after the crowd disperses, McDaniel’s staff makes the state senator available for “a few basic questions.”

This sort of easy openness has been McDaniel’s approach since he started running, and it never hurt—it made a nice contrast with Cochran, actually—until the videotaping story. He spent a week fielding leading questions about how he surely must know more than he was letting on. By the time I get to McDaniel, and ask whether the TV ads spotlighting the videotape will backfire, he has perfected a nonanswer answer.

“Here’s the thing,” he says. “What matters in this race are the issues. Sen. Cochran has been avoiding the issues. There’s a reason he’s avoiding the issues.”

What follows is a recitation of the campaign platform. The videotape story is a “distraction,” he says, and then says again. Campaign manager Melanie Sojourner, who called the Cochran campaign to denounce Clayton Kelly and was rewarded by having her voicemail leaked, stands nearby tapping on her phone. “The voters of Mississippi, they’re not going to let any distraction take away from the business at hand.”

Less than two hours later, Mississippi Tea Party leaders assemble in Jackson to face the press and reiterate why they support McDaniel. They cannot officially coordinate with McDaniel, but they are speaking his language. Jenny Beth Martin, the president of Tea Party Patriots—its “Citizens Fund” is spending half a million dollars on McDaniel ads—refers cryptically to a “distraction” that should not affect the race. Leaders from Tupelo in the north to Biloxi on the Gulf Coast lay out just how untrustworthy Cochran is. Why, he even allowed the Senate’s immigration bill to proceed to a vote—what else can the Chamber of Commerce coax from him if he wins?

The event is opened up for questions. None of the assembled press asks about immigration, the debt, or even the Tea Party’s ground game. The questions are all about the videotape.

“I think I know just about every one of you in the press here,” says Roy Nicholson, who founded the Central Mississippi Tea Party. “I think I have met just about every one of you. I have to tell you, I’m very disappointed in you. You keep going after the sensational. Go after the facts that are critical of the lives of people!”

More Tea Party leaders grab the microphone. “The press is supposed to be the Fourth Estate,” says Laura Van Overschelde. “It is your responsibility, it is your job, to report what is important to every Mississippian. Not some sensational story you might be interested in!”

The press conference sputters to a close, as some activists decamp to a nearby Chick-fil-A and some stay to plead their case. They remind the press that this is a race about issues and the “scandal” albatross is draped around the wrong guy. Why did anyone even bother to snoop around Thad Cochran’s wife? Because she’s been there for more than a decade, and since then, as meticulously reported at Breitbart.com, Cochran has taken dozens of junkets with his executive assistant Kay Webber. One activist, who doesn’t necessarily want to get into it and lower the tone of this race any further, muses about how Webber has been pictured traveling on side-junkets, with the congressional wives.

Had the race shaped up differently, the rumor mill might be churning about this. While the Tea Party is rallying in Jackson, Cochran is storming the state on his own campaign bus, stopping off in Hattiesburg. It’s there, according to two sources, that a group of suspicious-seeming young voters start asking Cochran about Webber. Cochran counters that the campaign recognizes these “voters” from their memberships on a pro-McDaniel Facebook page.

The senator presses on without sweating any of this stuff. While covering Cochran’s bus tour, Politico confirms that he was rattled by the intrusion into his wife’s privacy, and has visited Rose Cochran in the home a few times since the break-in happened. But he betrays no anger or worry about the aftermath. On a visit to Poplarville, Cochran is given a short tour of the city’s courthouse before taking three minutes to talk to reporters.

“I couldn’t imagine why they’d want to be taking photographs of Rose,” he says. “What we did as way of response was advise the local law enforcement.”

I ask Cochran why he considers the story important enough to make the focus of TV ads. “There are a lot of people running ads,” he says. “Not just the candidates. I can’t control other people’s right to free speech, and I’m not going to try to. This is strictly a local law enforcement issue, as far as I’m concerned. It doesn’t come under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Senate.”

That is a confusing answer. The ad came from Cochran’s campaign, complete with the 76-year-old’s voice confirming that he “approve[s] this message.” Maybe I asked about it in a confusing way, or maybe the senator has settled on a total-aloofness strategy ever since approving the ad.

Regardless, the controversy has freed up Cochran to campaign like what he is—a 36-year senator who wants to serve in a Republican majority. On Thursday morning the Cochran bus stops at an emergency training session in Biloxi’s convention center, overlooking the Gulf of Mexico that overran this place in 2005. At that time, before the Tea Party, Cochran got Congress to nearly double the amount of money it initially pledged for Hurricane Katrina relief. When McDaniel suggested that some of the funds were misspent—a perfectly ordinary Tea Party position—Cochran’s campaign pounced. How could the state risk replacing a senator who brought home funds with one who questioned how to get them?

On Thursday, five days before the polls open, Cochran ambles around the convention center shaking hands and swapping short anecdotes about growing up in Mississippi. There is no Tea Party rage, and certainly no gossip. Robert Latham, the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency’s director, guides Cochran around the room and back to his bus, then muses about what a great senator he’s been. Can he lead a fight against Obama? Honestly, who cares?

“What you see on the Gulf Coast here now would not have happened without him,” says Latham. “FEMA funds just don’t put you back. Without the [Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery] money he got, this coast would still look like it did after Katrina. And now he’s in a position to maybe become chairman of appropriations again.”