The True Cost of the Louisiana Purchase

The United States didn’t buy a huge tract of land from France. It bought the right to displace Native Americans from that land.

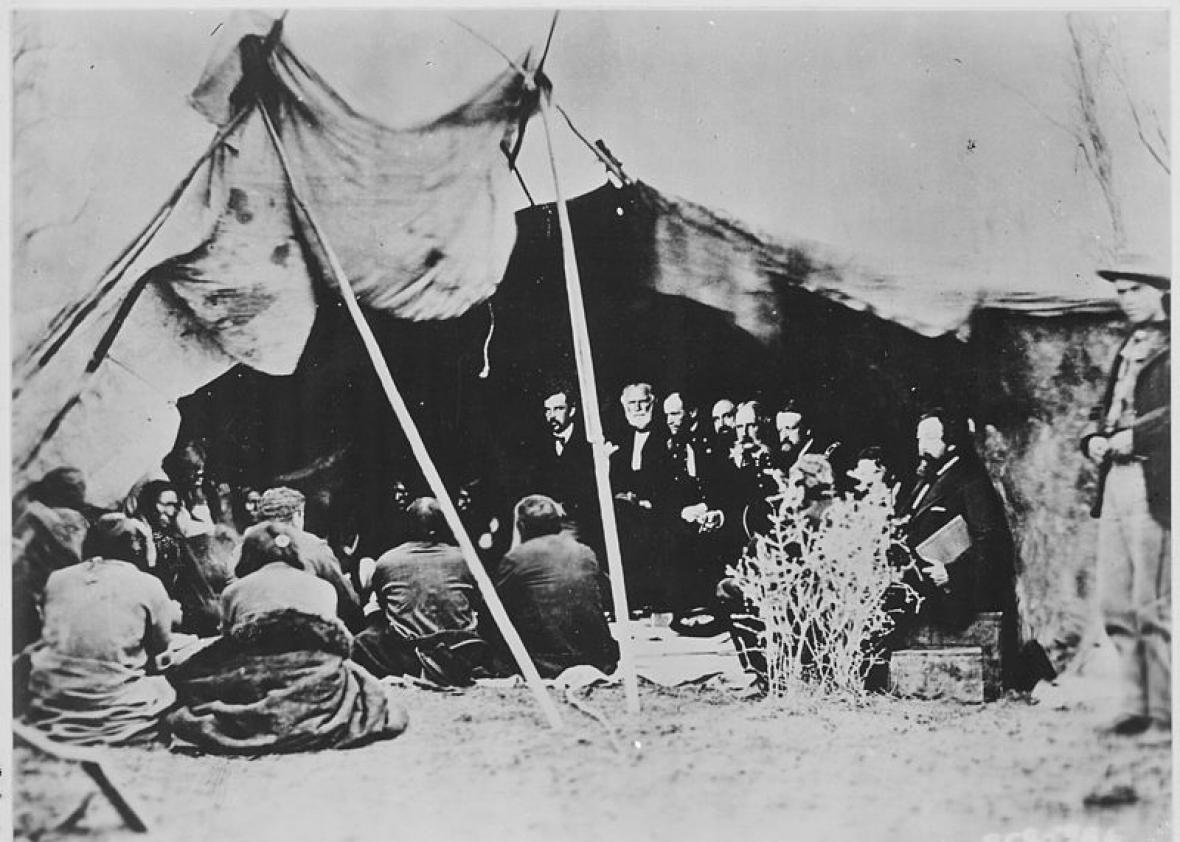

Wikimedia Commons/White House Historical Association

It’s a familiar chapter in our history, part of the triumphant narrative of westward expansion: In 1803, the United States bought a massive chunk of North America, and we got it for a song. Spain had ceded the Louisiana Territory to France, and Napoleon, in turn, offloaded it to American diplomats in Paris after the Haitian Revolution ruined his plans for the New World. Vaguely defined at the time as the western watershed of the Mississippi River, and later pegged at about 827,000 square miles, the acquisition nearly doubled the national domain for a mere $15 million, or roughly $309 million in today’s dollars. Divide the area by the price and you get the Louisiana Purchase’s celebrated reputation as one of the greatest real estate bargains in history.

This view of the purchase got a big push at the turn of the 20th century, around the time of its centennial, as leading intellectuals like Henry Adams applauded its agreeable price (he said “it cost almost nothing”) and illustration-hungry textbook authors made it the centerpiece of a benign vision of U.S. territorial growth. Maps used in classrooms—and emblazoned on everything from souvenir coins to cigar boxes and T-shirts—have burnished this reputation for generations. But the traditional narrative of the purchase glosses over a key fact. What Thomas Jefferson purchased wasn’t actually a tract of land. It was the imperial rights to that land, almost all of which was still owned, occupied, and ruled by Native Americans. The U.S. paid France $15 million for those rights. It would take more than 150 years and hundreds of lopsided treaties to extinguish Indian title to the same land.

The interactive below, designed using a geodatabase built for an article in the March issue of the Journal of American History, maps the long history of the Louisiana Purchase for the first time. It tracks 222 Indian cessions within the Louisiana Territory. Made by treaties, agreements, and statutes between 1804 and 1970, these cessions covered 576 million acres, ranging from a Quapaw tract the size of North Carolina sold in 1818 to a parcel smaller than Central Park seized from the Santee Sioux to build a dam in 1958.

Historians have long known that Indians were paid something for their soil rights, but we’ve never been able to say how much. The closest we had was a guess—about 20 times the acquisition price, or $300 million—floated in the 1940s and erroneously cited as gospel ever since. Figuring out how much the United States has actually spent to extinguish Indian title to the Louisiana Territory, tracked here from 1804 through 2012, yielded a figure much higher than anyone previously imagined—and yet still far from what the land was actually worth. All told, it adds up to about $2.6 billion, or more than $8.5 billion adjusted for inflation.

This animation maps 222 transfers of land to the U.S. government from the Native American nations that controlled the large tract commonly known as the Louisiana Territory. The transfers, or cessions, were made between 1803 and 1970. The animation also tallies payments made to those nations, for the original sales and as the result of later legal settlements.

Note: You'll notice, as you watch, that many areas were ceded multiple times. This happened for two reasons. First, some tracts were claimed by multiple indigenous groups, and the government paid them separately. Second, the government often moved groups from tract to tract, generating new claims to property it had already acquired. You'll also notice that some areas, including a large patch of the modern-day state of Louisiana, appear not to have been ceded at all. In most of these cases, the U.S. simply seized the land without paying anybody. Neither contemporary nor historical reservations are shown.

This animation maps 222 transfers of land to the U.S. government from the Native American nations that controlled the large tract commonly known as the Louisiana Territory. (For the complete interactive, please view this page on a larger screen.) The transfers, or cessions, were made between 1803 and 1970. The animation also tallies payments made to those nations, for the original sales and as the result of later legal settlements.

Note: You'll notice, as you watch, that many areas were ceded multiple times. This happened for two reasons. First, some tracts were claimed by multiple indigenous groups, and the government paid them separately. Second, the government often moved groups from tract to tract, generating new claims to property it had already acquired. You'll also notice that some areas, including a large patch of the modern-day state of Louisiana, appear not to have been ceded at all. In most of these cases, the U.S. simply seized the land without paying anybody. Neither contemporary nor historical reservations are shown.

The trouble with the textbook version of the Louisiana Purchase lies with its easy reduction to a real estate transaction. Europeans had only colonized a tiny fraction of the territory by 1803. Over those areas where they had established control, France sold the United States the right to tax and govern. Over the rest, it sold the right to expand political authority into Indian country without the interference of other would-be colonizers (overlapping British and Spanish claims were settled in 1818 and 1819). In these sections of the purchase, the U.S. acquired the exclusive right to invade or negotiate with indigenous inhabitants for control of their land: to take it by force or buy it by contract.

This right was called “pre-emption,” and it existed merely because those who claimed it said it did, which is why you’ll often find it entombed in scare quotes nowadays. But the distinction between real estate and pre-emption is not a minor or academic quibble. It’s essential to understanding how Thomas Jefferson himself understood the Louisiana Purchase when the deal reached his desk at the White House in July 1803, and it informed the system of treaties that soon began transferring to the federal government the Indian lands west of the Mississippi.

Federal authorities preferred acquiring Indian land by treaties because it was a more humane, and cheaper, method than outright war. But the treaties were backed by the looming threat of violence. The deals the government made specified compensation that came in a variety of forms, from one-time disbursements to annuities, goods, services, and more. In the allotment era, it became increasingly common to promise indirect compensation in the form of pledges to manage assets in tribal trust funds generated by the sale or lease of reservation land. Most arrangements for direct payments have long since ended. They were either broken, amended, exhausted, or, in the case of permanent annuities, commuted for lump sums. Just one lonely line item for Indian land ceded in the Missouri River Valley survives on the federal budget: $30,000 a year to the Pawnees of Oklahoma for 9,878,000 acres of what’s now Nebraska and South Dakota, ceded in 1857.

The breathtakingly stingy offers from the U.S. government reflected the power imbalance between the parties. The first Indian cession within the Louisiana Territory established the mold. In November 1804, a delegation of Sac and Fox Indians came to St. Louis to try to prevent U.S. retaliation for the murder of three squatters on Sac and Fox land in modern-day Missouri. There they found themselves pressured by William Henry Harrison, then the governor of the Indiana Territory and the newly formed district of Louisiana, into signing away 3.6 million acres straddling the Mississippi, about 1.6 million of them within the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase. In return, the Sac and Fox got a one-time delivery of $2,234.50 in goods, followed by an annual shipment worth $1,000.

In 1973, a federal commission found that this arrangement amounted to a valuation of a half a cent an acre for the ceded land. It also found the part of the Sac and Fox cession west of the Mississippi had a market value of 60 cents an acre in 1804. To make the Sac and Fox whole, the commission ordered an additional payment of 59.5 cents per acre, or $1,969,585, for the portion of the cession within the Louisiana Territory. Interest wasn’t part of the settlement, which enabled the government to pay a debt calculated in 1804 dollars with cash from 1973.

That was hardly the worst of it. In 1935, the Blackfeet, Blood, Gros Ventre, and Piegan successfully sued the United States for seizing more than 12 million acres in Montana by executive order in 1874. They had received nothing at all for a tract nearly twice the size of Vermont. The court determined the land had been worth 50 cents an acre when taken, which would have meant a $6.1 million award, without interest. But in calculating the final payout, the court reduced the judgment by requiring the plaintiff tribes to pay back past government expenditures for their benefit, in this case, for the salaries of federally employed Indian agents, teachers, police, and interpreters; for the construction and maintenance of Indian agency buildings; for land surveys; and perhaps most egregious of all, for the cost of shipping their children off to Indian boarding schools. Such “offsets,” as they were called, would later be mostly abandoned as obscenely unfair, but not before they chopped this award down by nearly 90 percent, yielding a payout of $622,465.57, or about 5 cents an acre.

For more than a century, and without much fanfare, litigation like this has supplemented the payments for Indian land originally paid as part of treaties, agreements, statutes, and executive orders. Indian claims cases for broken or unconscionably iniquitous treaties have been in the courts continuously since the 1880s. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy was stunned to find lawyers tabulating debts for land acquired in the 19th century when he toured the Department of Justice in 1962. In the heat of last year’s presidential race, it went little noticed when the Obama administration announced a round of tribal trust fund settlements in September.

Because these awards were arrived at after long delays, and typically excluded interest or any consideration of value not dictated by markets, they ultimately served more to quiet claims than deliver justice. This is why the Sioux rejected the most famous award, a 1980 Supreme Court judgment for $106 million for the taking of the Black Hills after nearly 60 years of litigation. While the court admitted that the 1876 agreement had been coerced with threats of starvation (and that it violated an earlier treaty from 1868), its decision left no room for what the Sioux actually wanted. As the Dakota novelist Elizabeth Cook-Lynn explained, the court added insult to injury by sanctioning a brazen theft, then adding, “we will now pay you X-millions of dollars, and the Sioux have said, ‘No, we want to talk about return of stolen lands.’ ” Nearly 30 years later, the judgment remains uncollected.

Most awards from the 20th century heyday of Indian claims litigation—in the Court of Claims through the 1930s and later the Indian Claims Commission from 1946 to 1978—were far smaller than the sum the Sioux rejected. In the past 25 years, cases have generally involved smaller amounts of land and a limited range of mineral or water rights disputes, which have made larger settlements politically possible. These settlements have generally been resolved by congressional acts ending costly and time-consuming litigation. An act passed in 1992, for instance, delivered $90.6 million to the Standing Rock Sioux for 56,993 acres lost to the dam project that created Lake Oahe in the late 1950s, a $14.1 million award plus 31 years of interest. An Osage settlement act in 2011 brought $380 million for mismanaged mineral rights. This belated turn toward equity illuminates just how little compensation was issued for land and resources previously. Settlement acts passed since the 1990s represent nearly a quarter of the total expenditures mapped here while covering only about 1 percent of the land cessions.

In total, more than two centuries of payments on original agreements, court awards, and settlement acts represent more than 99.5 percent of the United States’ expenditures to secure title to the Louisiana Territory. It’s a thicket of payments so dense and deep that it would be impossible to venture through without a shortcut. The key to amassing the data presented here is forensic accounting reports, hundreds of them, compiled by a task force that operated out of the General Accounting Office, now the General Accountability Office, at the height of Indian claims litigation. It was charged with combing through old records to determine how much the United States had spent on past Indian treaties and agreements. The reports it issued provided the research into the fiscal history of U.S.-Indian relations that enabled the courts to say how much the Sac and Fox, or the Blackfeet, or the Sioux, or scores of other tribes had been paid for land cessions. The research was undertaken so painstakingly because it furnished the Department of Justice with the records of past payments, which were in turn used to protect federal coffers by adjusting final awards downward. It also amassed a long paper trail that, in conjunction with legal decisions, settlements, and other documents, makes it possible to assemble this $2.6 billion in transactions.

Arriving at that number is one challenge, interpreting it is another. Next to the price of French pre-emption, it looks like a gargantuan figure. But that doesn’t mean France sold low and Indian nations sold high. If $2.6 billion sounds like a lot, consider why the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline was scheduled for construction in the first place: Since 2010, more than $100 billion worth of oil has been pumped out of North Dakota, one of the 13 states eventually carved out of the Louisiana Purchase. Then consider that if the Sioux award for the Black Hills had included the value of the most productive subsurface mine to set up shop on the stolen land, then it would have needed to be adjusted up by more than $25 billion. Then ask how much the Sac and Fox award from 1973 would have been if it had included interest compounded at the same rate used for the Standing Rock Sioux settlement from 1992. You’d arrive at more than $51 billion 1973 dollars, or more than a quarter trillion today.

Even at $2.6 billion for all of it—or $8.5 billion, adjusted for inflation—the Louisiana Purchase remains an unbelievable steal. But not of the type we’ve been taught, a fleecing of the shortsighted French. To cherish the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 as one of history’s great real estate deals requires buying into a myth. The acquisition of France’s pre-emption rights in 1803 was a down payment on a continental empire that ran through Indian country. The land came cheap because of how little the United States paid the people who lived here long before the French laid claim to Mississippi’s western watershed.