History, or Just Horror?

Should archives make images of eradicated diseases and antiquated treatments available for the world to see?

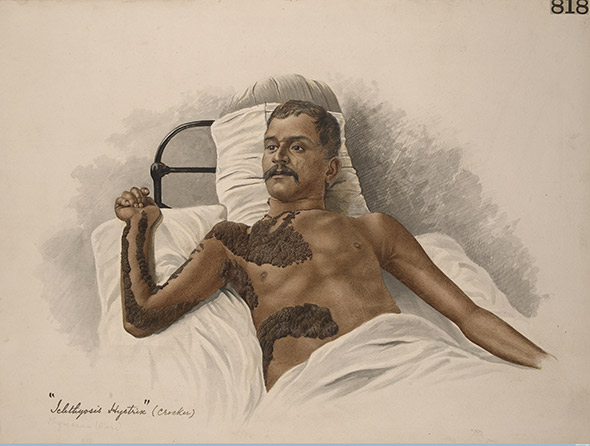

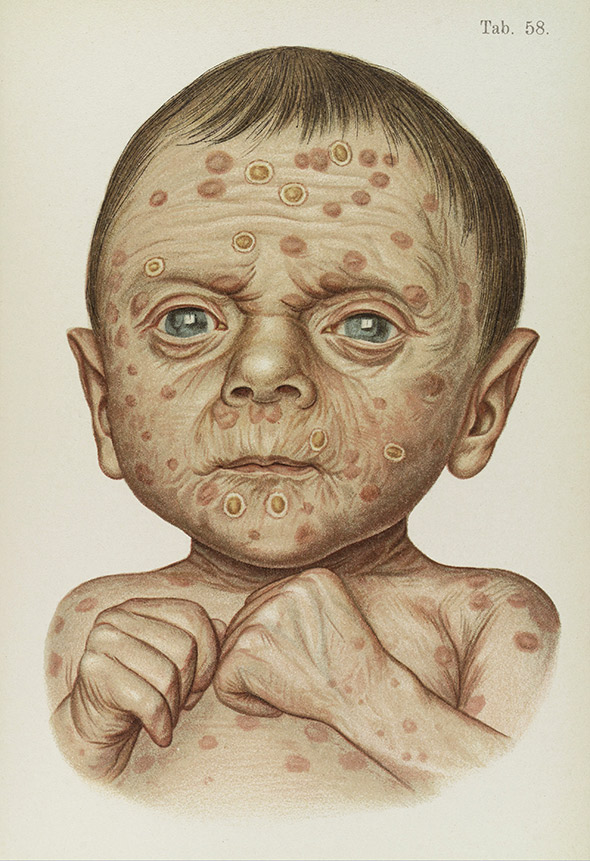

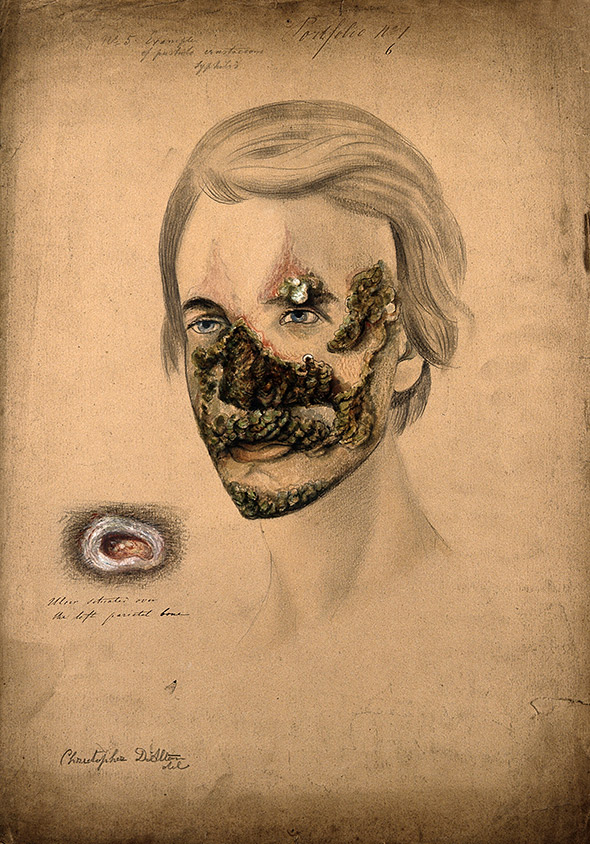

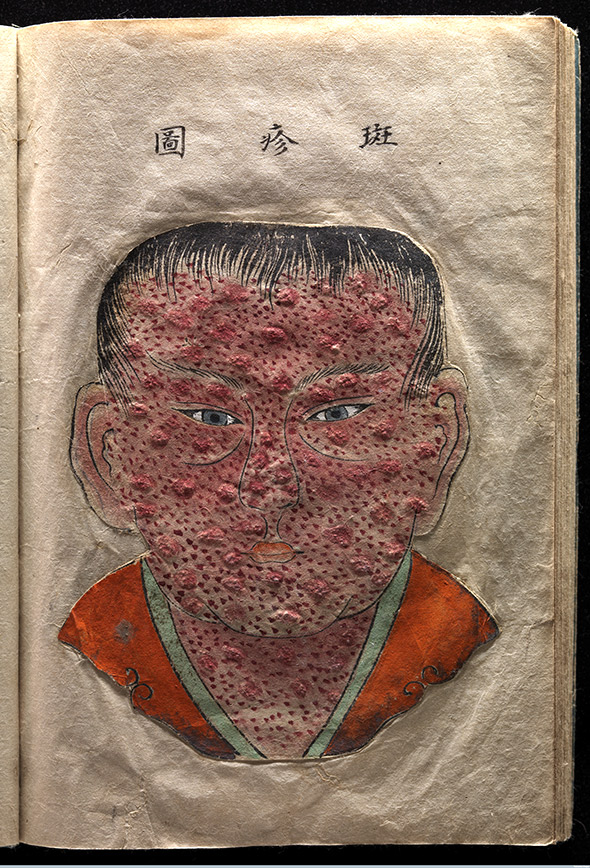

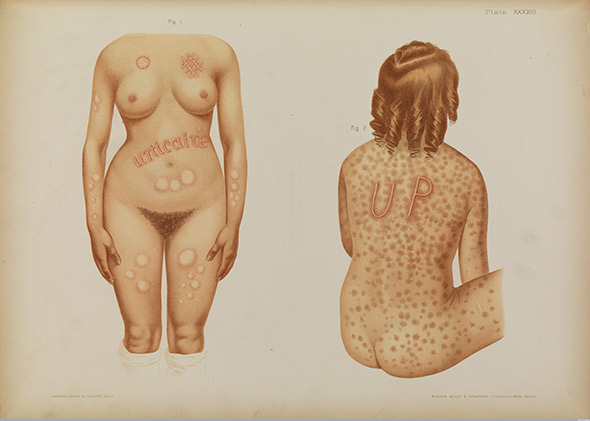

The recent book The Sick Rose: Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration is not to be leafed through lightly. The volume reproduces 19th-century images from the Wellcome Library’s collection of textbooks and medical atlases, alongside commentary by historian Richard Barnett. Some of its images of suffering patients have the power to rearrange the unsuspecting viewer physiologically, provoking nausea or painful waves of empathy.

The experience of looking at The Sick Rose, which is a well-curated print presentation of images that are freely available digitally on the Wellcome Images site, raises questions about historical medical images, and when and in what media it’s appropriate to view them. It’s one thing to take a beautifully bound book aside into a quiet armchair and have a one-on-one encounter with the face of a baby wizened by tertiary syphilis, or with a dignified man with a bulbous, untreated pendant tumor. It’s another to see the same faces flit by on Pinterest, Tumblr, or Twitter, in a jumble of other unrelated images and detached from Barnett’s context-providing scholarship.

The Sick Rose is organized by afflictions, most of which are now rare in the Western world: cholera, gout, tuberculosis, advanced stages of syphilis. On the Internet, the patients’ suffering runs the risk of being seen as “vintage”—almost funny in its awful extremity and its distance from our own time. In a blog post about the process of assembling and later promoting The Sick Rose, Barnett admitted to “a sense of unease” about sending the images off into the world, worrying about the “kitsch, knowing, and emptily ironized attitude” that could greet the images. (When Wired ran a slideshow of photographs from Sick Rose in May, for example, it was headlined “Awesomely Gross Medical Illustrations From the 19th Century”.) Over Skype, Barnett told me: “These are all images of something that happened to someone somewhere. They aren’t imagined.”

As historical medical images go digital, scholars and archivists are being forced to weigh the benefits of disseminating the undoubtedly important and interesting record of the evolution of medical practice with concerns that the images will be misused and misunderstood. Making the images available will almost certainly lead to some tone-deaf uses, lacking empathy and regard at best—exploiting the shock value of a disfigured face or body at worst. On the other hand, digitization of the kinds of images that were once available only to researchers with the means to travel to archives can do a lot of good. Such visibility can raise awareness about past wrongs, facilitate connections between historians and the families of former patients, even provide us with a new way to think about our own mortality. (Because there are good arguments on both sides, and because these medical images can be disturbing to some readers, we’ve chosen to put the photos we’re publishing with this article behind a digital scrim, which allows you, the reader, to decide whether to view them.)

Here’s one case that shows how far such digitized photographs can slip from their contexts. Art historian Suzannah Biernoff has written about the fate of a group of patient images from the Gillies Archives. These are the World War I-era records of Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup, in the U.K., where plastic surgeon Harold Gillies headed a special unit treating injuries that required maxillofacial surgery. Gillies commissioned artists and photographers to document his patients’ presurgical injuries, using the images to plan his team’s approach.

These photographs ended up on the Web as part of a mid-2000s exhibition titled Project Façade (now archived via the Wayback Machine). The project, which was funded by the Wellcome Trust’s SciArt Production Award, was a collaboration among artist Paddy Hartley; Dr. Andrew Bamji, a rheumatologist who acts as curator of the Gillies Archives; and Dr. Ian Thompson, a surgeon and designer of facial implants. The artwork that Hartley made with inspiration from these archives later formed the basis of an exhibition at London’s National Army Museum. The project, Hartley writes on his website, was meant to explore the impact of veterans’ wartime injuries and subsequent facial surgeries on their lives.

But the digital images had another life after the exhibition had closed. Some photographs from the Project Façade archive ended up used in the design of the genetic mutants (“splicers”) that players of the videogame BioShock must battle. One of the patients in the photographs, Henry Lumley, a pilot trainee, was injured on the day of his graduation from flying school and lived with his injury for a year before being admitted to Gillies’ care. Lumley died of postoperative complications, at age 26. (Here’s his page on the Project Façade website. And here’s an image of the BioShock character in question.) Lumley and his fellow patients are now forced to wander about in virtual space, made into monsters for the entertainment of gamers.

Does this matter, given that many (most?) BioShock players will never know who these men were in real life? Biernoff writes that British culture during the World War I perceived death in battle as glorious, but facial mutilation was seen as almost shameful—a “fate worse than death”—and images of soldiers injured in this way were censored, lest they diminish morale. So even if gamers never realize that the characters they’re seeing on screen were once real men, it can still feel like these men, ostracized in life, are being wronged again when they’re trotted out as digitized monsters. As Wellcome Library archivist Natalie Walters pointed out in a post on the connection between BioShock and the Gillies Archive: “That nearly 100 years later comparable images are used to frighten people in a computer game, gives us a glimpse into what life must have been like for people who sustained such disfiguring injuries.” (She adds: “How courageous these men were to allow themselves to be photographed with extensive injuries, and to undergo treatments that frequently made them look worse before they looked better.”)

Dr. Andrew Bamji, the Gillies Archives’ curator, told me over email that he approached the game’s developers after finding out about this use and succeeded in contacting one. “I pointed out that the use of identifiable men in the context of the game was an appalling way to treat the memory of veterans,” Bamji wrote. “He apologized and assured me that no further such images would be used, and there the matter ended.” Bamji drew a clear distinction between the use of such images in a project like BioShock, where they were disassociated from the names and stories of the patients, and Hartley’s Project Façade. “I have no problem with the display of images in a historical context, as without this people do not understand what war can do.”

Should we restrict access to upsetting digital images to people who we can be sure will perceive them in proper context? Michael Sappol, a historian at the U.S. National Library of Medicine who has written about historical and contemporary medical display, has an argument to the contrary. The NLM’s digital collections have recently posted a series of silent medical films from between 1929 and 1945, some of which represent what Sappol calls “difficult subjects”: leprosy, electroshock, schizophrenia. Sappol mentions, in particular, this 1929 film made at Cook County Hospital in Chicago, which shows four children who are dying of rabies. The patients convulse, struggle, bleed from the mouth; they’re inconsolable, even as gloved adult hands reach from off screen to hold them or offer them water.

Sappol doesn’t think it should be the job of the librarian or archivist to decide that the public can’t handle looking at such images. “We’re stewards of these historical materials,” he told me. “They don’t belong to us. They belong to everybody. … I would not like to act on behalf of the subjects and arrogate to myself the job of being some kind of policeman of ‘who can view.’ ” With the NLM’s electroshock therapy films from the 1930s, Sappol says, “Some of the people in this film … look like they certainly do not consent to the procedure, and it’s disturbing to see. I could say ‘This person doesn’t want to be on camera, they’re being humiliated.’ But this is something we can learn from. If we never get to see this, who gets to know?” The curiosity we feel about such images, he argues, isn’t shameful, but simply human.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that some subjects prefer visibility. “This is the case with the Thalidomide Trust archive, which contains medical case files on people born with severe birth defects after their mothers took the drug thalidomide to relieve symptoms of morning sickness in the late 1950s–early-1960s,” Wellcome archivist Helen Wakely wrote to me. “The views of thalidomiders themselves on what should happen with their case files vary widely, but some definitely want their files and images made available for research as a deliberate act to open up debate.” Of course, there’s no way to ask the patients whose bodies appear in The Sick Rose whether they would prefer to be seen or remain hidden. But the modern example of thalidomide shows that we shouldn’t assume that publication is tantamount to violation.

Nor should we assume that the Web is a less serious medium than the bound-and-printed book. Historian Miriam Posner, who wrote her dissertation on medical filmmaking, is also a digital historian committed to making her sources publicly available. In 2010, Posner posted about the ethical quandary she faced when asked to collaborate with a producer at NPR’s show Science Friday on a slideshow of lobotomy photographs. Neurologist Walter Freeman, who carried out more than 3,500 of the procedures, photographed and filmed his patients before and after their operations.

“I haven’t previously posted these photographs on the Web, and I even have reservations about using these photographs in academic presentations,” Posner wrote. Though they’d been published before, they’d been used for Freeman’s purposes: to prove that lobotomy was a good thing. Posner wondered what kind of message she’d be sending by making them available online.

But Posner ultimately went ahead with the Science Friday slideshow, reasoning that by asking viewers to take a second look at the “before” images of patients, which Freeman presented for his own purposes as “broken,” she might be able to show that “these faces contain more possibilities than Freeman ever saw.” A commenter on Posner’s post wrote that he had recently learned that his grandfather, who he’d never met, had been institutionalized and lobotomized in West Virginia, where Freeman did some of his work. The commenter wrote: “I have never seen a picture of [my grandfather], never, ever, and I don’t care if it is a picture of him having this done I just want and need to see a picture of him so MUCH. Can you tell me how to get to these archives?” If Posner hadn’t gone ahead with Science Friday, it might have been much harder for the commenter to find her; the connection might not have been made.

Finally, there’s a spiritual argument for making such images available. Even if medical images might be misused, Michael Sappol says, “I don’t want that possibility to prevent these things that are really amazing documents of the human experience from being seen. … We can learn from them, they can redeem us in some way. They can provide us with some kind of curriculum of human suffering. … Looking at them makes life richer and deeper.” Barnett, despite his misgivings, agrees on this point: “There is a power behind these images, there is a power they have over us, and we have to acknowledge or respect this at some point.” He compares the images to a “secular vanitas,” referring to the 17th-century Dutch paintings of skulls and other symbols of decay that were meant to remind the viewer of human mortality. For modern viewers, Barnett says, images like those in the Sick Rose might remind us: “This is the body, and the end that we all come to.”

Still, a vanitas requires space for contemplation—a space the Web seems ill prepared to offer. Susan Sontag’s final book, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), was written as the Web was in the process of scattering photographs to the four winds. Sontag wrote that photographs of suffering could be a “memento mori” and serve as a still point around which to contemplate mortality. But she wondered how this might work—or fail to work—in “a modern society,” where “space reserved for being serious is hard to come by.” If she thought that about art galleries, books, and television, one wonders what she might have made of Pinterest.

I wonder if we can evolve technologies of looking on the Web that solemnize and sacralize. Do the overlays we’ve used in this article, which require you to read the caption and affirmatively make the decision to view each image, do this, or begin to? Or is the veil over the image just another provocation, a “dare you to click”?

Perhaps the answer might be image or video files that contain within them a trigger that activates a program blocking the rest of the Web. Just for a minute, or two, you’d be forced to look, see, and feel, without distraction. Like a visitor sitting at a patient’s bedside, you’d bide a while with a fellow human, a witness to our collective frailty.