A Filibuster FAQ

What the Reid Rule changes, what it doesn’t, and the rest of your filibuster-reform questions answered.

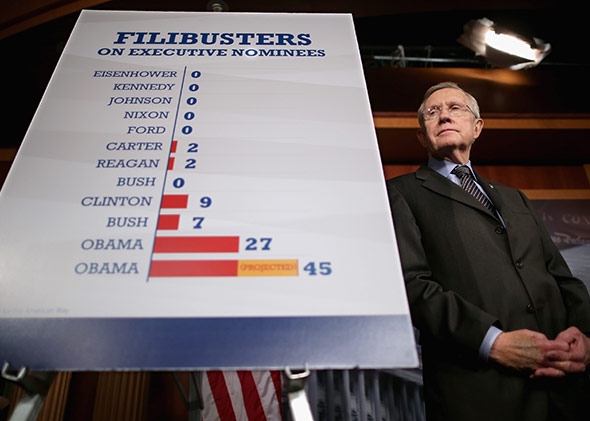

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Listen to David Plotz and Emily Bazelon discuss the filibuster vote on the Gabfest Extra.

The Senate on Thursday afternoon voted, 52–48, to eliminate the use of the filibuster against the majority of presidential nominees. The controversial move—widely known inside the Beltway and among editors hungry for page views as the “nuclear option”—had long been threatened by both parties when either found itself with control of the White House and more than 50 but less than 60 seats in the 100-member Senate. But, until today, those threats had remained largely just that, with the majority party unwilling to risk a major change to the Senate’s long-standing and often arcane rules.

Assuming you don’t spend your day hanging out at the Senate’s virtual reference desk, you probably have questions. Have no fear, Slate’s got answers.

Remind me, what’s a filibuster again? Is that where some lawmaker sees how long he can stand on his feet without taking a bathroom break?

That is indeed a filibuster, but not the one we’re dealing with here. While there are several different varieties of filibusters, all have the same goal: delaying or derailing some kind of Senate action. The maneuver is traditionally deployed by one or more senators as a last-ditch effort to prevent a vote—either on a specific piece of legislation or on a presidential nomination—that they can’t otherwise defeat in simple, 51-vote-majority situations.

The most well-known variety is the Mr. Smith Goes to Washington-style filibuster, when a single senator takes to the floor to talk for as long as he or she can. These talking filibusters can earn the senator plenty of press coverage but usually deliver only fleeting victories. Eventually, even the most long-winded and big-bladdered senator must rest. Once he or she does, the Senate can pick up where it left off and proceed to a vote.

The filibuster’s more common form—the one we’re dealing with here—is significantly less captivating but much more effective. In these cases, all the filibustering minority needs to do is band together to ensure the majority party doesn’t have the 60 votes it needs to invoke what is known as cloture, a parliamentary step needed to bring up an issue for a final vote in the Senate.

So Democrats killed all non-talking filibusters?

In a word: No. In a few more: The change ends the filibustering only of most executive branch and judicial nominations through the second, more common filibustering tactic.

More importantly, it does not change the equation for big-ticket votes like Supreme Court nominations or actual legislation, both of which will still need 60 votes to overcome a potential filibuster on their way to passage or confirmation. If Senate Democrats wanted to bring up a climate or immigration bill for a vote tomorrow, they’d still need 60 votes to do it. The same goes for when there’s the next opening on the high court.

That doesn’t sound nearly as Senate-shaking. How big of a deal is this really?

It depends where you’re sitting. Taken in a vacuum, many Americans might be more surprised to learn the status quo: that one of the two congressional chambers doesn’t actually operate exclusively under majority rule. That said, the change is certainly a big one for an institution that prides itself both on occasionally head-scratching traditions and in providing outsize power to the minority party (as opposed to in the House, where a simple majority carries the day).

So when the New York Times calls today’s move “the most fundamental shift in the way the Senate functions in more than a generation,” and the Washington Post describes it as a “historic turn,” the papers are correct—but in no small part because the upper chamber has long been resistant to even the smallest of changes. (This is a place, after all, where senators are still discouraged from addressing one another by name while on the floor.)

Still, despite the comparisons to a nuclear holocaust, it’s worth remembering that the confirmation rules were never written in stone. The threshold for nominees was actually dropped to 60 votes from 67 in 1975, and the cloture rules have also been rewritten a half-dozen or so times in smaller ways in the past century.

How did Democrats actually go about making the change?

Under the common interpretation of existing Senate rules, the majority party always had the ability to tweak the chamber’s ground rules with a simple majority vote. So this might be where the somewhat overblown nuclear analogy holds up best—the bomb was already built; Harry Reid only needed 51 votes to press the launch button.

That sounds remarkably easy. Why’d they finally do it now?

The specific dispute that finally triggered the change was over a handful of Obama’s nominees to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, widely considered the second-most powerful federal court in the land because of its role in reviewing cases involving federal agencies. (It’s also seen as a stepping stone to the Supreme Court; four of the current nine justices spent time on the D.C. bench.) Republicans repeatedly filibustered those nominations, arguing that the appellate court is underworked and does not need additional judges to do its job—a position that rather conveniently prevents Obama’s nominees from swinging the powerful bench to the left.

While Democrats say that Republicans left them little choice in the matter, the decision to finally push through the reform might also be explained by the fact that given the current political climate on Capitol Hill, the rewards simply outweighed the risks. Democrats were faced with one of two unappealing choices: keep the filibuster and get nothing done, or change it and still get nothing done legislatively but at least confirm a whole bunch of judges and high-level administrative officials.

It also doesn’t hurt that today’s news, at least temporarily, changes the D.C. conversation to a topic that isn’t the troubled Obamacare rollout—something Republicans wasted no time pointing out today.

What does the change mean in practice? Why is everyone treating it like such a big deal?

The thermonuclear-themed fear in Washington is that the change will fundamentally alter how the Senate works. We know it will allow Democrats to quickly confirm many of President Obama’s nominees that have languished in procedural limbo. But what we don’t know is how it will affect regular business in the always-has-been-always-will-be slow-moving Senate, and even in the GOP-controlled House.

Because Senate Republicans still have the power to filibuster legislation, it’s not hard to imagine that the minority party will do so even more frequently than they already do as an easy and rather direct expression of their displeasure with Thursday’s change. House Republicans, meanwhile, have one more reason not to sit down at the table with their Democratic colleagues.

There’s also the chance that if the GOP regains control of the upper chamber in 2014 as they hope, they could use the same procedural maneuver to extend the change to include Supreme Court nominees. “You may regret this a lot sooner than you think,” Sen. Mitch McConnell warned Democrats today.