Europe Didn’t Win

Greece’s leaders appear to have folded. But the rift between its citizens and the rest of the continent won’t be so easily fixed.

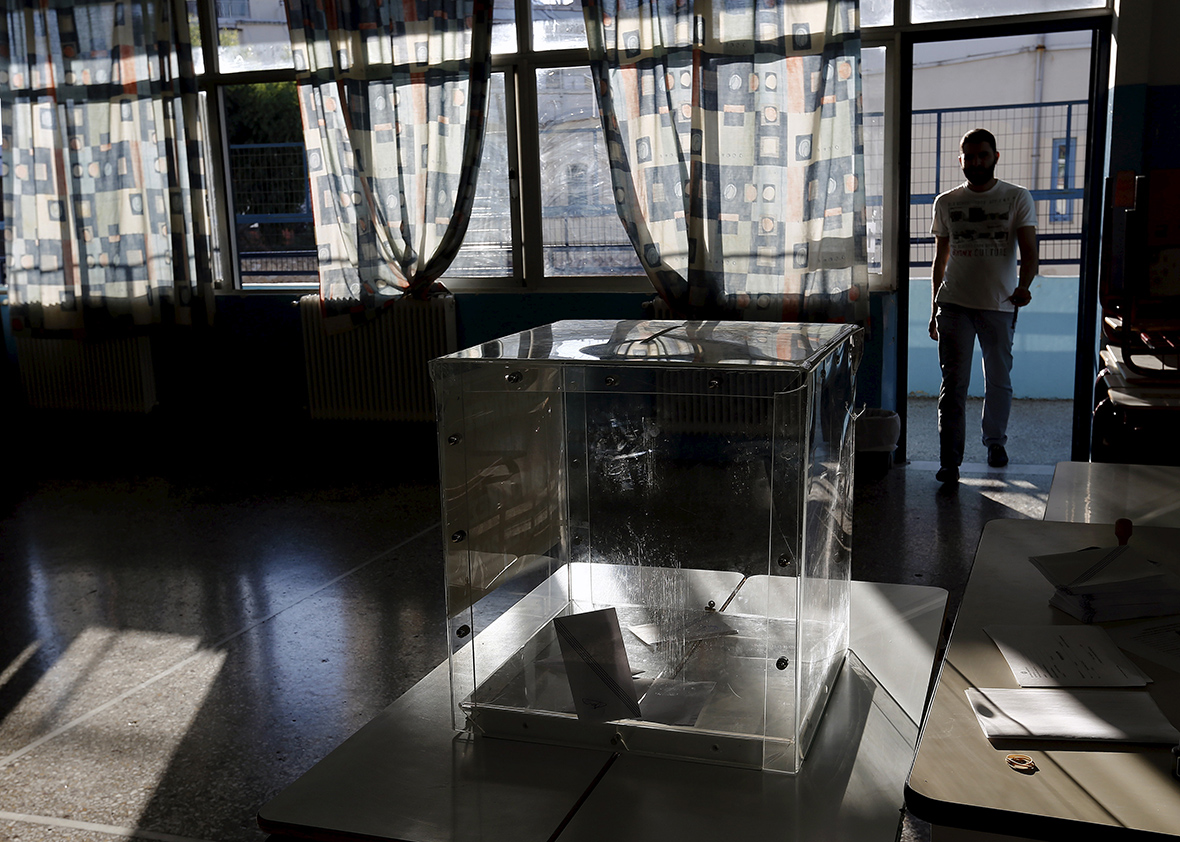

Photo by Alkis Konstantinidis/Reuters

ATHENS, Greece—On Thursday the appliance stores in Kifissia, an upper-class suburb here, were packed with Greeks scrambling to buy expensive imports. They were doing so with cash; Greek-issued credit cards are no longer accepted within or outside of the country. The more dire-sounding residents I met claimed that, within months, Greece will no longer be importing iPhones; others just wanted to spend their money while they still have it. Elsewhere in Athens, lines were still forming outside of ATMs, many of which had run out of cash altogether.

The mood in Athens this week was at once embattled and proud, erratic and panicked. A wave of political resignations has swept Greece since Sunday’s referendum, in which Greeks were asked whether they agreed with the latest bailout terms offered by the country’s creditors. “No” won resoundingly in every province of the country. Antonis Samaras, the former prime minister, stepped down as head of the New Democracy Party that night; Yanis Varoufakis, Syriza’s finance minister, left his post the next day. There have been taunts of violence. Thanos Tzimeros, a former leader of the minor political party Recreate Greece, is under investigation for taking to social media and calling for a forceful overthrow of Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras. “We are at war here,” Panos Kammenos, the defense minister and head of the Independent Greeks Party, declared after several of his associates threatened to vote “yes” in the referendum.

Tsipras’ Syriza Party ascended to office in January amid a stalemate between Greece’s two political machines, New Democracy and PASOK, which had swapped rule over the country for the past 40 years. It happened on the back of a fundamentally contradictory promise: Tsipras told Greeks he could end the austerity policies that have handicapped public services for the past six years, even while keeping Greece on the euro. In February, he was given a four-month extension by European leaders to renegotiate the terms of Greece’s debt. That extension ended on June 30. The next payment to the European Central Bank is due July 20.

Relations between Syriza and Greece’s European creditors have been disastrous since Tsipras took power. The conventional wisdom is that Syriza overplayed its hand and is now being put in its place by the Brussels bureaucracy. With Tsipras’ seeming capitulation Thursday in the form of a new bailout proposal that is fairly similar to the one voters rejected and includes major concessions, Europe’s leaders may appear to have finally won the standoff going into a possibly final summit Sunday. But they have done damage to the sanctity of the European project. And Syriza’s fortunes notwithstanding, Europe has failed to cow the Greek left.

Throughout the entire crisis, Europe has treated Greece in belittling, often outright infantilizing ways. The hostility toward Syriza has been astonishing for two reasons. As Varoufakis has argued repeatedly, Syriza remains France and Germany’s best chance at getting any of their money back. It has no incentive, and possibly ability, to give it back in the event of a Greek exit from the euro, which is likely if Greece defaults on its bailout obligations. It is important to remember Syriza’s promise to remain in the eurozone. Tsipras recognizes that his popular support would collapse should that change. For its part, Germany has failed to recognize that its intransigence has in fact given continued life to Syriza, currently the only game in town in Athens.

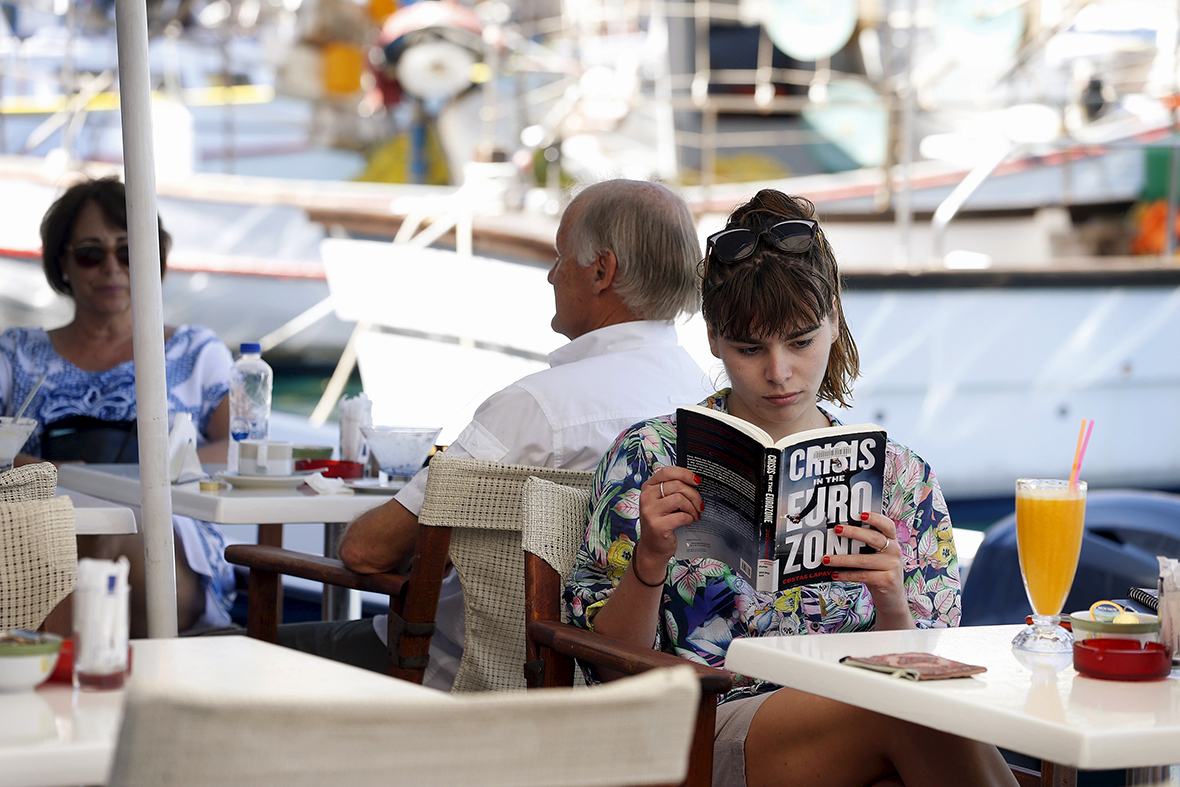

European officials profess no trust in Syriza, but their picture of Syriza is highly deceptive: Attacks tend to psychologize the party for being reckless, or amateurish, or goaded by some sort of historical trauma or inferiority complex. If anything, the last two weeks have made it sufficiently clear how Europe, as an institution, has its own dissembling ways of operating. Until last week, EU officials had managed to block the release of a June International Monetary Fund report declaring that the only viable solution for Greece’s debt was to have most of it written off; in other words, the IMF vindicated much of what Syriza has been arguing for months now. Incidents of this sort have eroded the investment that many Greeks, regardless of political affiliation, have in the EU as a bureaucratic concept—if not their faith in the very idea of Europe. Historically speaking, the implementation of austerity has rarely resulted in renewed social trust, and the new, harsher rounds of austerity that Brussels has devised for a potential third Greek bailout package will likely only further polarize Greek society.

Three months ago, the lesson of Syriza’s struggle to extract a new deal may have been that the European technocracy can’t be ruffled by a pesky left-wing party on Europe’s fringe. Today, the lesson may be that the failure to create a political union on par with a monetary union not only affects the fortunes for democracy at the national level, but in Europe as a whole. Europe’s attempts to oust Syriza from power by flaunting its weaknesses lack even the semblance of discretion; the idea has been openly acknowledged by northern European leaders. In another context this might be called an attempted coup from afar.

The second reason why Europe’s intransigence toward Syriza is shocking is that Tsipras is not threatening the world of global capital or the structural integrity of the EU. He climbed to power on promises that, among other things, he would spearhead a revolution of working-class people against Europe’s political elite. But Tsipras has accomplished nothing of the sort. He no longer speaks about such things. His actual negotiating points with the EU for the past few months have been over relative trifles: reductions in the value-added tax percentages of certain Aegean Islands, changes in the retirement age of state-sector employees. These are largely symbolic fights—Tsipras needs to prove to his base that he’s tough enough to extract something from lenders—and winning them will no doubt afford certain financial relief to Greeks who have come to expect little from their politicians. But it can hardly be said that Tsipras is confronting the EU in ways that, say, PASOK would never have dreamed. He’s just doing it with a vast base of popular appeal, and with all eyes in Europe on him. This makes him an annoyance to European elites, but also a potentially useful paradigm: He may serve as a precedent for Spain and Portugal if he successfully renegotiates bailout terms, and he likewise becomes a warning to governments in those countries if he fails.

Syriza is by no means blameless in any of this. Its handling of negotiations and its exercise of power have been abysmal. Time and again Tsipras has misled his electorate. He claimed that a deal with creditors would be reached on Tuesday, when in fact he had no new terms to present to Brussels. He has made few of his tactics transparent to the Greek people. Few Greeks last Sunday knew exactly what they were actually voting on—problematic not least because Tsipras has said that he would never lead Greece out of the European Union without first consulting the Greek people. Last Sunday could be used as the “evidence” he needed that Greeks do want to leave. But the majority, according to opinion polls, still don’t.

The deeper problem with Syriza is a kind of bravado fueled by populist tactics. The alliance it made with the far-right Independent Greeks in January now appears less a case of odd bedfellows and more like a perfectly natural partnership. There’s something pettily nationalistic in Syriza’s activation of Greek pride against the creditors. Of course this is now the strange position of the left across Europe, traditionally opposed to nationalism; patriotism has become a last plank of resistance against technocratic incursion. In Greece, right-wing elements—including the neo-Nazis—join the left in opposing this. There’s also something uncomfortably opportunistic about Syriza’s obsession with the German midcentury, be it the wartime loans forcefully extracted from Greece, or the forgiveness of German wartime debts in 1953.

There’s hope for the Greek left beyond Syriza. It partly derives from the methods Syriza used to rise to power. As early as 2008, when anti-austerity rallies and anti-fascist demonstrations began hitting Athens, Syriza deliberately refused to politicize them. Instead the rallies remained organic gatherings of citizens, who were taking to the streets voluntarily, not because their politicians were telling them to. Today, there’s a tremendous social base on the Greek left unconnected to Syriza that supports the party but is not wrapped up in its political fate. The vast majority of these people sit to the left of Syriza and would argue that Tsipras is not being nearly radical enough when it comes to reforming Greece’s place in the eurozone.

This social bloc, comprised primarily of the youth, now bears a heavy hand in the Greek political scene. Its capabilities were on full display on Friday night, at the final “no” rally in Syntagma Square—organized by Syriza, but not very well promoted by it. Those who spread the word about attending that demonstration were members of organizations like ANTARSYA, an anti-capitalist movement. They combed the streets, working-class neighborhoods, and the parks, explanatory pamphlets in hand; they spray-painted sidewalks and bed sheets with NO! and slung them across various symbols of Athens—Lycabettus Hill, different departments of Athens University. The opposing Yes! campaign was another thing altogether, waged predominately via crisp, professionally shot video ads that aired on YouTube and Greek TV.

The results were clear. One hundred thousand Athenians showed up to the “no” demonstration in Syntagma Square—by some accounts, the largest gathering of Greeks in a single place since the collapse of the Junta more than 40 years ago. Those supporting the “yes” vote in the Panathenaic Stadium numbered just 20,000.

What does this actually mean for Greece right now? Two things. First, the “no” victory in the referendum, while hardly deserving of the jubilation it received, at the very least showed that democracy, even if in the form of a plebiscite, is still alive in Greece on the ground. Second, if Syriza falls from power, the basis for its popular support—the movements, the social activism—still exists; Syriza, or at least the ideas behind it, won’t go the way of PASOK, the center-left party that imploded as soon as its political foothold vanished and its European cash flows dried up. Should Greece stay in the eurozone, Germany will still have to reckon with this element of Greek society, which is now enraged by Tsipras’ concessions.

That’s why Friday evening, tens of thousands of Greeks flocked to Syntagma Square—not only to protest Europe’s harsh yoke, but also what many consider their prime minister’s great betrayal. The majority of the protesters were from unions controlled by the Communist Party; a small portion were from the Greek far right. The police were out in full force, although Syriza had run on the promise that the presence of riot police would be tempered. Almost every protest that’s occurred while Syriza’s been in power has been pro-government. This was different. “It’s just like it was six months ago,” a teenager named Konstantinos told me. “The police are back, and so is the austerity.”