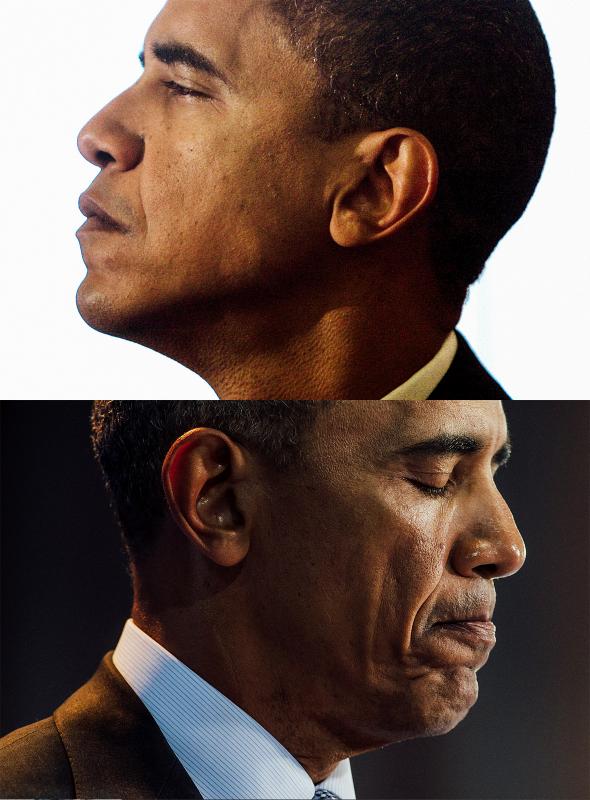

The Obama Paradox

Our first black president has an unyielding faith in the goodness of America. It got him elected. And it will cost him his legacy.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Tim Sloan/AFP/Getty Images, Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images.

The myth of Barack Obama usually begins with his speech to the 2004 Democratic National Convention, and for good reason—it was the speech that jump-started his political career, putting the then–state senator on the fast track to national office. But it wasn’t the speech that made him president. That speech was delivered at a moment of crisis. His former pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright, was in the middle of a media firestorm over a sermon he had given in 2003 in the wake of the Iraq invasion. “No, no, no. Not God bless America,” thunders Wright in the now-infamous video. “God Damn America!”

Had this just been the case of a controversial preacher, Obama might have survived by ignoring it—treating it as a distraction from “the issues.” But Wright was more than controversial; he was black. And he was speaking in a black religious and political tradition that condemns America for its treatment of black and brown people, for the genocide of natives and the enslavement of Africans, for internment and displacement. In Wright’s eyes, America was sinful, and until it atoned for those sins, God would deny His blessings. Not God Bless America. God Damn America!

For Obama, who built his political appeal on his distance from this rhetoric—from the tenor and tone of traditional black politics—Wright’s sermon was a disaster in the making. To operate in the mainstream, to attain influence and power, black public figures have to navigate a narrow strait of acceptable behavior. They cannot indulge their anger or give way to their passions. And for Obama, who sought an office all but reserved for white men, he had to prove that he wasn’t an Al Sharpton or a Jesse Jackson, that he held no resentment or frustration with the country. And so on March 18, 2008, Obama delivered an address in Philadelphia now known as his “A More Perfect Union” speech. In it, he repudiated Wright’s anger without dismissing its sources, and along the way he demonstrated the qualities that have defined him as president: a sense of balance, a willingness to look to the better angels of his opponents, a belief that there is always common ground.

Now, on the eve of his farewell address, 10 days before the inauguration of Donald Trump, the most celebrated speech of Obama’s career hits the ears a little differently, as does the sermon that necessitated it. What the Jeremiah Wright of “God Damn America” lacked in admiration for the country, he made up for in clarity about its nature and its sins. He refused to look away from the dark corners of American history, or treat them as mere “zags” on the road to progress. He was clear-eyed about racism as a motive force in American life. He knew we cannot escape our history.

Had Obama absorbed those lessons, he would have been better prepared for the backlash that will be the undoing of his legacy. Had Obama not been so quick to explain away Wright’s pessimism, he would have seen the dangers that lay ahead. But then he likely wouldn’t have been Barack Obama, president of the United States. This is the great irony of the moment: The optimism that helped Obama reach this office—the same faith in our ever-perfecting union—is wholly inadequate in the face of the revanchist rage that gave us President Trump.

“The profound mistake of Reverend Wright's sermons is not that he spoke about racism in our society,” Obama said in Philadelphia.

It's that he spoke as if our society was static; as if no progress has been made; as if this country—a country that has made it possible for one of his own members to run for the highest office in the land and build a coalition of white and black; Latino and Asian, rich and poor, young and old—is still irrevocably bound to a tragic past.

Progress has been made, argues Obama. We are no longer bound to the past. And in making that case, Obama also presents himself as fundamentally different from Wright. He will not damn America. He believes in it. He trusts it. He is black, yes, but he doesn’t hold Wright’s grievance—Wright’s anger. You see this earlier in the speech, when Obama repudiates Wright in even more direct fashion. The reverend “expressed a profoundly distorted view of this country—a view that sees white racism as endemic, and that elevates what is wrong with America above all that we know is right with America.”

It’s not that “A More Perfect Union” was insincere. Far from it. That speech captures the essence of Obama’s beliefs and his rhetorical posture, which centers itself on the essential unity of all Americans, on our common hopes and aspirations. It reflects his “unyielding faith in the decency and generosity of the American people” and his faith in the institutions of the United States. And while the speech didn’t foreshadow any of the events of the next eight years, it offered a guide to how Obama would generally approach controversy and tackle obstacles: with generosity, political ecumenicism, and good faith.

It’s a civilized approach for a civilized time. But now, unfortunately, is not a civilized time. As Obama leaves office, he confronts a new president who seeks to cast him aside as an almost monstrous imposition on a so-called “real America.” Who stoked racial, religious, and misogynistic hatred to win power, who represents a profound threat to our liberal, pluralist democracy, a harbinger of authoritarian nationalism. In this precarious moment, Obama’s approach isn’t enough.

Indeed, you can feel the inadequacy in how Obama has approached the transition to Trump, treating him as a normal political figure with the same basic respect for process and norms. In his final press conference of 2016, Obama stressed that he would continue “cooperation” with the president-elect, and that concerns over hacking should be a “bipartisan issue,” which he hopes will be a focus in the Trump White House. “My hope is that the president-elect is going to similarly be concerned with making sure that we don't have potential foreign influence in our election process,” Obama said. It’s true some of this is strategic, a deliberate attempt to normalize Trump and impress on him the constraints of the office. But that, in turn, reflects Obama’s belief in institutions and process, despite the real chance those institutions and processes will fail to constrain Trump’s will to power.

It’s worth returning to Wright’s sermon. There’s no doubt that it is a flawed document, marked at points with conspiratorial thinking. But it also contains vital insights built around the idea that one should not confuse “government” with “God.”

Wright explains why. He tells his congregation that “governments lie.” He emphasizes this by pointing to racism: “This government lied about their belief that all men were created equal. The truth was they believe all white men were created equal.” But then, he reminds his audience, “governments change.” And he emphasizes this point in a way Obama would appreciate.

Prior to Abraham Lincoln, the government in this country said it was legal to hold Africans in slavery in perpetuity. Perpetuity’s one of them University of Chicago words, it means forever. From now on. When Lincoln got in office, the government changed. […]

Prior to the Civil Rights and Equal Accommodations laws of the government in this country, there was black segregation by the country, legal discrimination by the government, prohibited blacks from voting by the government, you had to eat in separate places by the government, you had to sit in different places from white folk because the government says so, and you had to be buried in a separate cemetery. It was apartheid American-style, from the cradle to the grave, all because the government backed it up. But guess what? Governments change!

Wright doesn’t reject the idea that America can move past its racial sins. For him, however, there are limits. Why? Because “governments fail,” too.

When it came to treating her citizens of African descent fairly, America failed. She put them in chains. The government put them in slave quarters, put them on auction blocks, put them in cotton fields, put them in inferior schools, put them in substandard housing, put them in scientific experiments, put them in the lowest paying jobs, put them outside the equal protection of the law, kept them out of their racist bastions of higher education, and locked them into position of hopelessness and helplessness.

Wright sees that there’s been progress, but he also sees profound continuity between the past and the present. In this sermon, racism is a fundamental feature. This is what brings him to “God Damn America for treating her citizens as less than human,” a line that nonetheless contains the possibility of change through redemption, but not the guarantee.

On Tuesday, Barack Obama will say goodbye. He’ll do so in Chicago, and he’ll do so echoing the themes of his political career. “We’ve run our leg in our long journey of progress, knowing that our work is and will always be unfinished,” Obama said in a recent interview previewing his farewell address, which is being billed as a “forward-looking“ and optimistic speech meant to inspire. “[R]emember that America is a story told over a longer time horizon, in fits and starts, punctuated at times by hardship, but ultimately written by generations of citizens who’ve somehow worked together, without fanfare, to form a more perfect union.”

Obama will end where he started, with a message of hope born of optimism, born of the idea that—even with inevitable hardship and pain—the arc of the universe bends toward justice. The problem is that we face more than potential hardship. We face an administration that seems determined to find out if the arc bends the other way as well. Trump and the reaction he rode in on have exposed the limits of Obama’s optimism. When we look to the past from the vantage of today, we see a story of progress: the enslaved person becomes free; the sharecropper escapes apartheid. But from their individual perspectives, time has no particular arc. The enslaved person does not see emancipation on her horizon; the sharecropper does not know if his children will have a better life. And even if justice eventually comes, it does not change that they lived lives defined by its antithesis. Obama’s vision of hope and change leaves this out. Jeremiah Wright’s does not. Rooted in a doctrine of sin, it has room for the idea that we can fall behind. It has room for the concept of a President Trump because it holds no illusions about the country and its institutions.

Obama rejected Wright’s vision with a speech that saved his campaign and made him president. Given our present circumstances, it’s clear he could have used a little of Wright’s insight. Obama saw his candidacy and ultimately his presidency as part of the story of American progress. But governments change, the pastor said. Things can and will get worse, our ever-perfecting union be damned.