Trump Country

Rural Americans have the power to pick our presidents. They just chose a politician who’s unwilling and unequipped to help them.

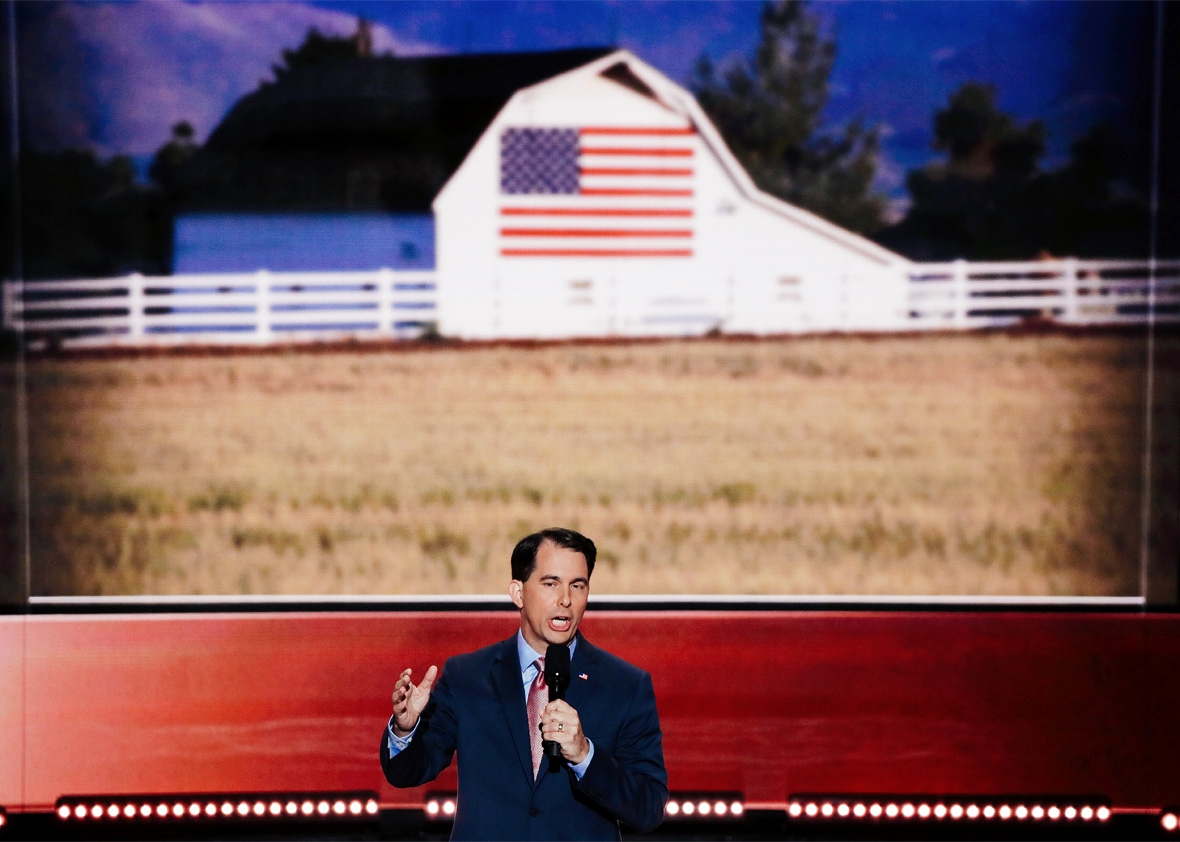

Mark Makela/Getty Images

Let’s talk about the cities, those warrens of cosmopolitans who failed to see the red wave until it washed them away. For nearly half a century, Democrats have worked to position themselves as America’s metropolitan party. After the Dems fractured over civil rights and Vietnam, leaders came away touting the New Politics, a platform for college-educated idealists worried more about quality of life than class warfare. The 1980s brought the Atari Democrats, a faction of market-friendly liberals interested in tech. Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, as chairman of the Democratic Leadership Council in the early 1990s, sought to build the platform for suburban moderates. Jesse Jackson disparagingly referred to the DLC as “Democrats for the Leisure Class,” and he wasn’t wrong. The party seduced and depended on wealthy suburbanites, and on yuppies streaming back to the inner city. It worked, for a while. It didn’t work in 2016.

Four years ago, Mitt Romney won just one U.S. county with a population density greater than 1,000 people per square mile, California’s Orange County. On Nov. 8, Orange County flipped to Hillary Clinton. While she lost some Rust Belt suburbs that Barack Obama had won in 2012, like Detroit’s Macomb County, Clinton made big percentage gains over Obama in and around Boston, Washington, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, Denver, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake City. For the Democratic nominee, running up the score in America’s densest locales was good enough for a popular vote victory—and a distant second-place finish in the Electoral College.

In winning the presidency, Donald Trump proved a national candidate could demonstrate not only a disregard for big-city concerns, but a gleeful, manic ignorance of how cities function and thrive. (His claim that the murder rate had reached a 45-year high, for example, was at once a race-baiting lie and a display of how little he cared to find out the truth.) The flip side to cosmopolitanism—the “rural consciousness,” in the phrasing of University of Wisconsin–Madison political scientist Katherine J. Cramer—is now both an identity and an electoral force. Trump won dominant support in rural America. He outran Romney by more than 40 percent in large swaths of the Midwest. His rural success was not confined to the Rust Belt.

Is this the world, envisioned by MSNBC’s Chris Hayes after Brexit, where politics is “a battle between cosmopolitan finance capitalism and ethno-nationalist backlash”? Not quite yet. But we’re approaching that binary. Trump’s core message was small-town nostalgia. Michelle Obama’s counter, that America is already great, is a line that only makes sense in America’s cities, where populations and incomes have continued to rise.

In short, the metropolis has economic power but little political power. The American countryside has limited economic power but vast political power. It’s always been true, but this year’s electoral map shows the gap is wider than ever. There are many explanations for what happened on Election Day, but the simplest one is this: We now have a rural party and an urban party.

The rural party won. And it won on a Trump-ish promise—stop immigration, close the door on refugees—that threatens metropolitan success and undermines rural America’s best hope for an economic renaissance.

* * *

Alex Wong/Getty Images

For the Democrats, the presidential vote had long come in from the union-friendly Midwest, until it suddenly didn’t. For all those years, even as “Democrats for the Leisure Class” hosted Tupperware parties in Bethesda, Maryland, Democratic voters in Midwestern towns and small cities stuck with the party. Hidden in the electoral map’s red hinterland were clusters of blue votes around small-town Main Streets. Whether Hillary Clinton lost those places because of NAFTA and declining union membership or because of fear of refugees, blacks, and Mexicans will be disputed for a long time. But she did lose those places, and she lost them badly. Erie, Pennsylvania, a regional center of 100,000 people, just voted Republican for the first time since 1984. Obama beat McCain by 20 points there. Nationwide, Clinton won the union vote by just 8 points, the Democrats’ smallest margin since 1984. In Ohio, according to exit polls, she lost it.

The collapse of the rural vote in presidential elections is, for Democrats, the continuation of a trend that started at the local level. Between 2006 and 2016, the Dems lost nearly 1,000 seats in state legislatures. The party now controls only 13 state legislatures. There are just 15 Democratic governors. (If Pat McCrory loses in North Carolina, that number would increase to 16.) On Tuesday night, Dems lost the governorship in Vermont and the state Senate in Minnesota, two of the last outposts of rural populism.

Wisconsin provides a particularly dramatic example of the Democrats’ decline. The state was once a crucible of progressive thought, the first to pass workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance laws. Its public university has long been one of America’s best. But no state lost a larger percentage of middle-class households between 2000 and 2013. Unions once represented 35 percent of the state’s workforce; today that figure is 11 percent. Over the past six years, Gov. Scott Walker has led a right-wing revolution to cut taxes, cut aid to schools and local governments, repeal collective bargaining rights, limit early voting, require voter identification, defund Planned Parenthood, and loosen gun laws. Progressive action at the local level has been quashed.

Katherine Cramer, the University of Wisconsin political scientist, calls this the politics of resentment. It is intimately entwined with the development of a rural consciousness, she posits, an anti-urban swell whose defining characteristic is not racism but a more generalized frustration about citizens’ inability to fight off the rise of high-density America, those cities where power, money, and even their own children concentrate. When politicians inveigh against “urban America,” they’re often stoking their constituents’ race-based fears. But “urban” is now also code for class, power, money, and the Democratic Party.

This ideological clustering is partly the culmination of Bill Bishop’s big sort, the theory that likeminded people increasingly live together in social and political echo chambers. But the movement of educated Americans to the metropolis is a larger issue. Globalization has, ironically, concentrated economic opportunity in a handful of places. Corporate consolidation has decimated regional centers, and even big cities like St. Louis. One Walmart manager can take the place of a dozen small-town entrepreneurs. Living beyond the metropolis is considered a sacrifice for young people with college degrees. You can get a fellowship to live on the depopulated coast of Maine, which cast its first electoral vote for a Republican candidate since 1988. You can get a free MBA from Stanford if you agree to live in the Midwest.

Basically, the status quo is working in cities, and a vote for Hillary Clinton was a vote for the status quo. Caveats abound. There are groups in the American city, particularly black and Latino communities, that are suffering. Wages are flat and the safety net is riddled with holes. The rent is too damn high. Displacement and homelessness are getting worse. Police departments are unaccountable for abuse. But if you zoom out, the distinction between densely and sparsely populated American counties is stark. In the most-recent economic recovery, large counties added new businesses while small counties lost them. Large counties, too, added millions of jobs; small counties barely added any. Workers in urban areas now earn as much as 33 percent more than their rural counterparts.

It may seem absurd to group metropolitan voters—Puerto Ricans in Morningside Heights, Amazon executives in Laurelhurst, oil workers west of Houston’s 610 loop—together as a demographic. But whatever blend of cosmopolitanism, diversity, openness, upward mobility, and optimism makes up the metropolitan consciousness, it was in unique, historical alignment with Hillary Clinton’s candidacy.

Democrats’ congregation in urban centers does not come in handy during presidential elections. Clinton’s surges around Boston’s Route 128 and in Montgomery County, Maryland, ran up the margins in states whose electoral college outcome is all but predetermined.* City dwellers don’t help win statewide elections either. To take one example, Democratic clustering in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh makes it virtually impossible for the party to control the Pennsylvania statehouse or win the majority of Pennsylvania’s seats in Congress. And that’s before you account for gerrymandering.

In the runup to Nov. 8, the same solution was offered to both electorally disadvantaged Democrats and economically disadvantaged Republicans: move. People on the left, including Alec MacGillis and my colleague Will Oremus, have argued that liberal Americans need to decluster from blue states to compete effectively in America’s farmer-favored political system. On the other side, Kevin Williamson of National Review argued in March that what Trump’s rural white supporters need most of all is a U-Haul, to move to places where they can find jobs.

Neither one seems likely to happen—Americans are less geographically mobile than at any point since 1948. Young Americans are not going to sacrifice their dreams to accommodate the country’s byzantine electoral system, which was designed to grant the franchise exclusively to landowners. Rural whites, in turn, will be buoyed by their candidate’s victory, at least until they are disappointed by his inability to turn back the clock to 1950.

* * *

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

The paradox of Trump country is that its greatest hope for economic renaissance lies in in-migration, in towns filling back up with industrious Americans. But the people that are best positioned and most willing to do that aren’t young hipsters in Los Angeles or Stanford MBAs. They’re immigrants.

The fact that immigrants are good for society shouldn’t need to be reiterated in this nation of immigrants. But it’s true: Immigrants are more likely to start businesses than native-born Americans. (In 2011, immigrants accounted for 28 percent of all new businesses in the United States.) They’re more likely to be self-employed. They’re more likely to work in crucial science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields. They make indelible contributions to American culture, of course. And they have long helped fill up, prop up, and revitalize downtrodden areas of American cities. Now, they’re doing the same in the countryside.

“Any revitalization of local areas is going to involve attracting immigrants,” argues Emilio Parrado, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania. Latinos have flocked to places like Duplin County, North Carolina, and Lexington, Nebraska, to take jobs in meat-processing plants and other nonunion agricultural and industrial jobs. “These plants do revitalize the economy,” Parrado says. “Latinos go to these places, open stores. You go to these places and you see the Mexican restaurant, the Mexican grocery. But there’s racial tension.”

According to a study by the Center for Rural Strategies, a Kentucky nonprofit, nonmetropolitan counties with the highest percentages of immigrants have lower unemployment. (The cause and effect here is uncertain; migrants follow jobs, but they also create them.) The flip side to that story, as reported recently in the Wall Street Journal, is that counties that have “seen the most rapid demographic change” in the past decade and a half voted overwhelmingly—67 percent to 29 percent—for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton. America’s small towns are in desperate need of new residents. Yet in those places where that infusion has arrived, white voters chose to line up behind a candidate whose xenophobia surpassed what most of us believed was possible in American politics.

If Donald Trump moves to restrict immigration and refugee resettlement, he will hurt the nation’s cities. Chicago’s population has stayed stable thanks to immigration from Mexico and to a lesser extent Central America and Asia. Philadelphia has grown for the first time in 50 years, thanks to immigrants. New York also owes its record population growth to foreign-born residents. But the places Trump will hurt the most are the ones that voted for him. Racial and ethnic minorities have accounted for 83 percent of rural growth from 2000 to 2010. Hispanics in particular were responsible for the majority of nonmetropolitan population growth between 1990 and 2010. According to William Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution, nonmetropolitan counties in the Midwest have seen their white population drop 9 percent since 2008 while the number of Hispanics (not all of whom are immigrants, of course) has risen by 18 percent. The numbers are similar in the Northeast, with the white population down 13 percent and the Hispanic population up 17 percent.

Refugees, too, have helped revitalize post-industrial and agricultural areas of upstate New York. There are hundreds of thousands of homeless, country-less electricians, bakers, and farmers stuck in migrant camps in Jordan and Turkey. Why not, as a 2015 New York Times op-ed asked, let Syrians settle Detroit? “Refugees resettled from a single war zone have helped revitalize several American communities,” the authors wrote, “notably Hmong in previously neglected neighborhoods in Minneapolis, Bosnians in Utica, N.Y., and Somalis in Lewiston, Me.” Those possibilities have been foreclosed by Donald Trump’s election.

And what of the Democratic Party? Its presidential model isn’t broken. Clinton’s popular vote total will surpass that of John McCain, Mitt Romney, and Donald Trump. She lost the presidential election in three states by the combined margin of the crowd at a football game in Ann Arbor.

The fact that Democrats have a possible path to electoral victory four years from now shouldn’t obscure the structural limits of the party’s appeal. “The Democratic Party has to be focused on grassroots America and not wealthy people attending cocktail parties,” Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders tweeted last week. Sanders is right that a metropolitan party cannot compete in a pastoral political system. But the ideology that most distinguishes the Democratic Party from Trump-brand Republicanism—support for immigrants and racial minorities—is one that would improve the fortunes of those who handed it such a rousing defeat. This is the central irony of the 2016 election: Trump country has elected a president who will harass, deport, and bar the very people desperate to live there, the people who would help rebuild its small towns and cities.

*Correction, Nov. 14, 2016: This piece originally misidentified a highway in the Boston suburbs as Route 123. It is Route 128. (Return.)