The Democratic Party’s Racial Reckoning

In 1992, Bill Clinton had to pander to white bigots to win the presidency. In 2016, Hillary can call them what they are.

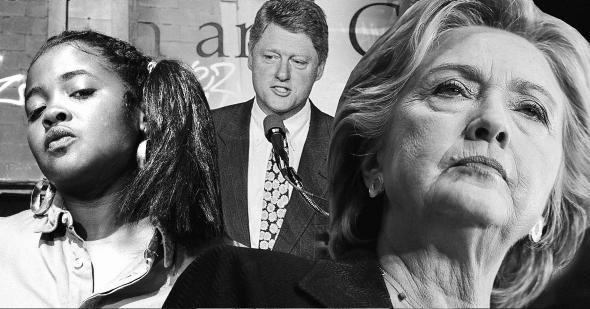

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Anthony Barboza/Getty Images, Greg Gibson/AP Images, and Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Anthony Barboza/Getty Images, Greg Gibson/AP Images, and Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

The day after the first presidential debate, all anyone wanted to talk about was the coup de grace: Alicia Machado, “Miss Housekeeping,” “Where did you find this? Where did you find this?” But the most remarkable exchange of that night had come earlier, when with a few blunt words Hillary Clinton reduced Donald Trump to peevish incoherence and, remarkably, conveyed the distance her party has traveled in the past quarter-century. If you listened carefully, you would have heard a kind of Sister Souljah moment, in reverse.

It happened after moderator Lester Holt pressed Trump on his birtherism. “Mr. Trump,” he said, “for five years you perpetuated a false claim of the nation’s first black president was not a natural-born citizen. You questioned his legitimacy. In the last couple weeks, you acknowledged what most Americans have accepted for years: the president was born in the United States. Can you tell us what took you so long?”

Trump tried to shift blame, pinning birtherism on the Clinton camp and its conduct during the 2008 Democratic primary. This is false. But more interesting than Trump’s answer was Clinton’s response. She didn’t just dismiss his claim. She pushed back in the strongest way possible. Trump “has really started his political activity based on this racist lie that our first black president was not an American citizen,” Clinton said. “There was absolutely no evidence for it, but he persisted.” She continued, tying the birtherism to a larger critique: “[R]emember, Donald started his career back in 1973 being sued by the Justice Department for racial discrimination, because he would not rent apartments in one of his developments to African Americans, and he made sure that the people who worked for him understood that was the policy. He actually was sued twice by the Justice Department. So he has a long record of engaging in racist behavior.” Clinton’s message was simple: From the beginning of his business career to the launch of his political one, Trump swam in a rank pool of prejudice and racist insinuation. And then, with Trump established as both a beneficiary and catalyst of American bigotry, she dropped the story of Machado, a former Miss Universe, on his head. “[O]ne of the worst things he said was about a woman in a beauty contest,” Clinton said. “He loves beauty contests, supporting them and hanging around them. And he called this woman ‘Miss Piggy.’ Then he called her ‘Miss Housekeeping,’ because she was Latina.”

In the narrative of this election, Donald Trump is the “politically incorrect” one in the race. He says what “people are thinking” and isn’t afraid of the reaction. For the most part this is nonsense. Trump’s political incorrectness is just a cover for run-of-the-mill prejudice. If people don’t blame Mexico for “sending rapists” over the border, it’s not because they’re cowed; it’s because it isn’t true. If there’s an actual norm restricting honest discussion for fear of giving offense, it’s around white racism. Hence the storm of criticism for Clinton’s “basket of deplorables” comment, condemned because it violated political custom—don’t attack the other side’s voters—not because it was untrue. “No. 1 rule of presidential politics. Okay to mock your opponent. Never a good idea to mock the electorate,” said Michael Barbaro of the New York Times on Twitter.

Clinton’s gaffe was to talk about bigotry plainly, without euphemism. And what’s striking, given that backlash, is that she’s continued to name and shame Trump’s racism.

It’s no small thing to call birtherism a “racist lie” in front of the largest-ever debate audience. Presidential candidates slam opponents for almost everything under the sun. But not racism. Not because it isn’t present, but because it risks alienating white voters who aren’t comfortable with accusations of racial prejudice or racist intent. But last week, facing an estimated 85 million viewers, Clinton did just that, in a way that wasn’t imaginable four years ago (when Barack Obama ran against Mitt Romney and his veiled racial appeals), eight years ago (when Sarah Palin fueled her nascent celebrity with raw white resentment), and certainly 30 years ago, when George H.W. Bush and the Republican Party stoked white fears of black crime for political gain, crushing Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis in the process.

What changed to make Clinton—a woman of profound political caution, the virtual avatar of modern-day Democratic centrism—willing to name racism when she sees it? To describe millions of voters as “deplorables” with racist and misogynistic views? To call the things what they are, even if it alienates voters?

The answer is straightforward. Clinton may represent the middle way of Democratic politics, but that middle way is substantively and electorally different from the middle way of the 1990s, when her husband was in office. Clinton can talk openly about white racism because she doesn’t need the old Democratic electorate.

“Weekend Passes” ad/YouTube

In the 1990s, Democrats needed white voters and struggled to pull them into the fold, in part because of the party’s liberalism and its strong identification with black Americans and black political interests. The closing months of the 1988 presidential campaign were a testament to this challenge. Using the case of Willie Horton, a convicted murderer who, on a furlough from prison, abducted and assaulted a white couple in their home, the Republican Party and the George H.W. Bush campaign portrayed the Democratic Party and its nominee Michael Dukakis as dramatically and disastrously “soft on crime.”

What’s key is that, implicitly, this also meant “soft on blacks.” Horton was a young black man, and as political scientist Tali Mendelberg writes in The Race Card, “news coverage of the message was highly visual, conveying the story with racially stereotypic imagery, such as Horton’s glowering mug shot.” In a nation still rocked by violent crime, Horton evoked potent stereotypes of black criminality and stood as a symbol of alleged liberal leniency for black criminals.

Dukakis lost. Badly. Bush captured more than 53 percent of the popular vote and earned 426 Electoral College votes from 40 states. It was a drubbing, among the worst in American political history. And in the aftermath of Dukakis’ defeat, the next Democratic nominee for president, Bill Clinton, watched, learned, and vowed that neither he nor his party would get Willie Horton’d—or, in the old George Wallace phrase, “out-niggered”—by the GOP again.

Running in 1992, Clinton danced a two-step. He tied himself to black voters and black communities, winning huge support through deft use of cultural affinity. He emphasized his Southern heritage: Here was a poor boy from Arkansas who could relate, personally, to the lives of many black Americans. At the same time, however, Clinton made a direct play to the cultural anxieties and political resentments of those whites who’d abandoned Dukakis for Bush. Midway through the campaign, he flew to Arkansas to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector. Rector had killed two people—including a police officer—and then tried to kill himself, suffering severe mental impairment in the process. Rector did not and could not understand his eventual fate, but Clinton would not pardon him. “I can be nicked for a lot,” the Arkansas governor reportedly said after the execution, “but no one can say I’m soft on crime.”

Anthony Barboza/Getty Images

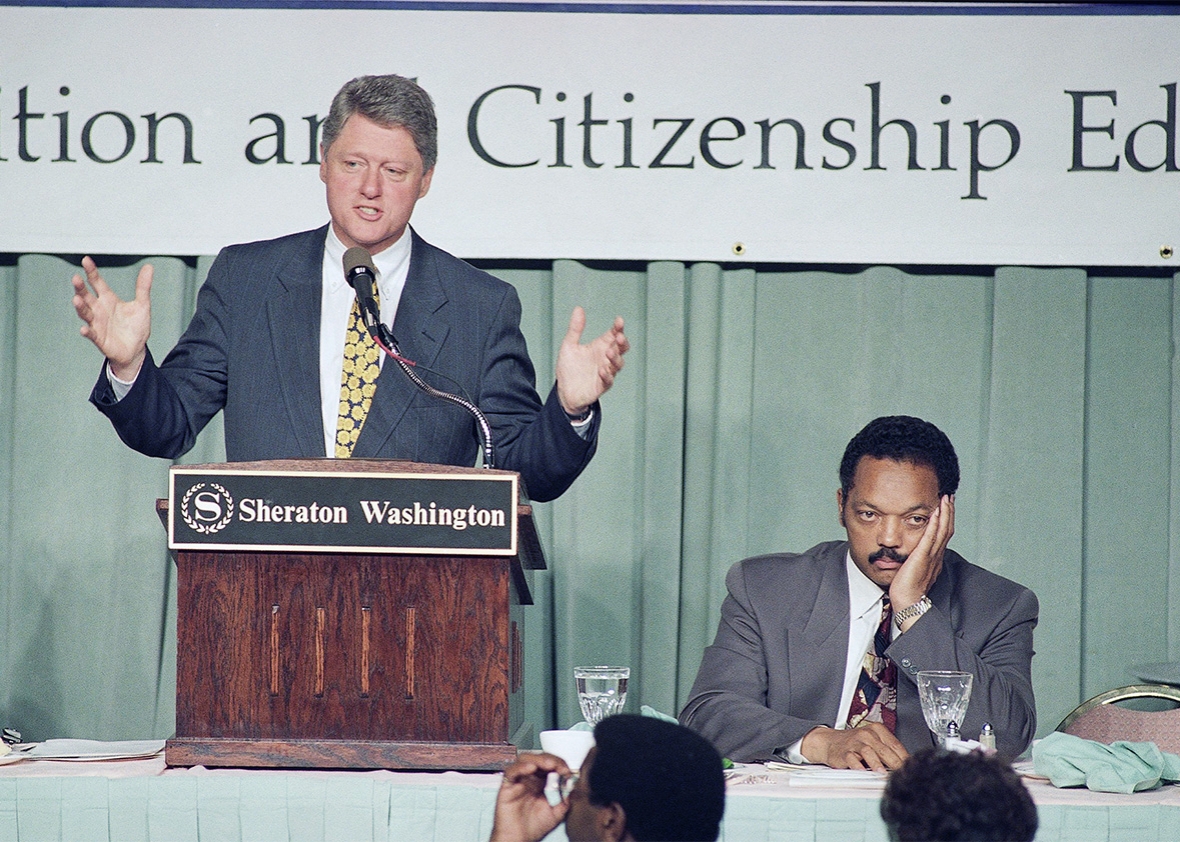

His most infamous move in this two-step came later, when Clinton agreed to speak at Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition conference that summer. In addition to Clinton, Jackson had also invited Sister Souljah, a rapper and activist then in the news for her heated remarks about the riots in Los Angeles. “If black people kill black people every day, why not have a week and kill white people?” she said in an interview with the Washington Post. Her music featured similar sentiments, all the more controversial given larger public concern with the rise of hip-hop as a mainstream cultural product. Clinton used the conference to condemn Souljah and distance himself from Jackson, in a direct play for white moderates. “If you took the words white and black, and you reversed them, you might think David Duke was giving that speech,” said Clinton of Souljah’s rhetoric.

Both moves would help Clinton win skeptical white workers and professionals, who worried that the Democratic Party was beholden to black voters. And in office, Clinton would continue the dance, pushing a controversial anti-crime bill and signing welfare reform in an effort to end “dependency” among low-income blacks.

Greg Gibson/AP Images

It was a politics indexed to white anxiety. The Democratic Party of Bill Clinton relied on voters who were unfriendly—even hostile—to racial liberalism. And it moved accordingly. Bolstered by the economy as well as these cultural moves, Clinton would claim the center of American politics, winning an easy re-election and eventually ending his term as one of the most popular presidents in recent memory, despite scandal and an impeachment attempt.

But that was then. Today, those voters—among them millions of working-class white men—are lost to the Democratic Party, in a shift that began under George W. Bush but accelerated under the presidency of Barack Obama. Democrats today win a smaller share of white voters—and the white workers in particular—than ever before. The home for those voters is in the GOP, under Trump, who turned a substantial majority with working-class whites into an overwhelming one, enough to win Ohio and Iowa and possibly other Midwestern states. But there’s been a backlash to this backlash. Trump’s success with working-class whites has come at the expense of the Republican Party’s historic advantage with college-educated and professional whites, who now favor Hillary Clinton. Increasingly, the Democratic electorate is shorn of those voters who are skeptical of racial and cultural liberalism or who vote on that skepticism.

Bill Clinton distanced himself from anything that smacked of identity politics or traditional liberalism. Hillary Clinton has not. This speaks to a larger reality in American politics. Racism—either virulent or implicit—is the enemy of progressive political coalitions. It’s either an obstacle to building those coalitions in the first place, or it’s a part of the process that unravels them. White departure from the Democratic Party cost it the Oval Office for nearly 20 years, and the effort to win those whites back yielded a disappointing and myopic centrism. But now those whites aren’t as central to Democratic presidential fortunes, and it has given many in the party the space they need to move in a more liberal direction. And looking at the tenor of Democratic policy debates over the past year—debates over how the welfare state should expand, not if it should—they have. Which is to say that the great upside of this shift is for the blacks, Latinos, and young people who form a critical part of the Democratic Party’s national electorate. Their demands for criminal justice reform, immigration reform, and broader economic reform—as channeled through the primary campaign of Bernie Sanders—aren’t a deal-breaker for national Democratic politicians.

The danger, as we see in this election, is that this imperils valuable electoral real estate. And in nonpresidential elections, it puts Democrats at a distinct disadvantage. It is hard to win back the House of Representatives, for instance, when you have little traction with working-class whites in the Midwest. At the same time, there’s an opportunity. A Democratic Party that doesn’t need to win more than a modest minority of working-class white men is one that can lean further toward racial liberalism, to mobilize its black and Latino supporters and to win over those culturally liberal whites. It can embrace comprehensive immigration reform, champion LGBTQ rights, and assail implicit bias without threatening its ability to win national elections. National Democrats can even dance a different kind of two-step, baiting prejudiced opponents into expressing that prejudice and condemning them for all the world to see. Not just to slam their opponents, but to mobilize their supporters. To show which side they’re on, and that they aren’t pandering to the wrong voters.

It’s what Clinton did with “deplorables,” and it’s what she did a week ago, demonstrating for nonwhite voters her distance from the racist corners of the electorate just as surely as her husband, in 1992, used Sister Souljah to demonstrate his independence from black interests. And it’s only possible because the Democratic Party of President Clinton is gone, replaced by the one built by President Obama and his allies. It’s a more liberal and more cosmopolitan Democratic Party, one that doesn’t see a national future in winning white workers from the GOP.

Hillary Clinton is still on track to win this presidential election. And barring an extraordinary—and unlikely—collapse in Trump’s support, she will do so with a revamped Obama coalition, comprising nonwhites; young voters; and an unprecedented number of moderate, suburban whites. She will have claimed the center of American politics, not by pandering to popular prejudices, but by rejecting them.

But the rhetorical freedom afforded by this racial and generational shift in Democratic politics has its costs. Broad coalitions are often shallow ones, and that's especially true here. The Obama/Clinton coalition isn’t large enough or deep enough to win the House of Representatives, and it seems, increasingly, that it isn’t large enough to win the Senate either. A President Hillary Clinton will enter office without the majorities she needs to pursue her agenda. If she can’t pursue her agenda, she can’t deliver promised benefits to her supporters. And as we’ve seen in the Republican Party, with this year’s presidential primary, leaders who can’t deliver are leaders who are vulnerable to backlash.

Democrats have crafted a new center over which a different Clinton will preside. How long it will hold is a question of enormous consequence to the progressive agenda.